The legacy of Pan-Africanism in African integration today

Virtual Meeting of the African Union Bureau and Chairs of Regional Economic Communities, Kigali, 20 August 2020. Photo: President Paul Kagame's official Flickr account, Creative Commons.

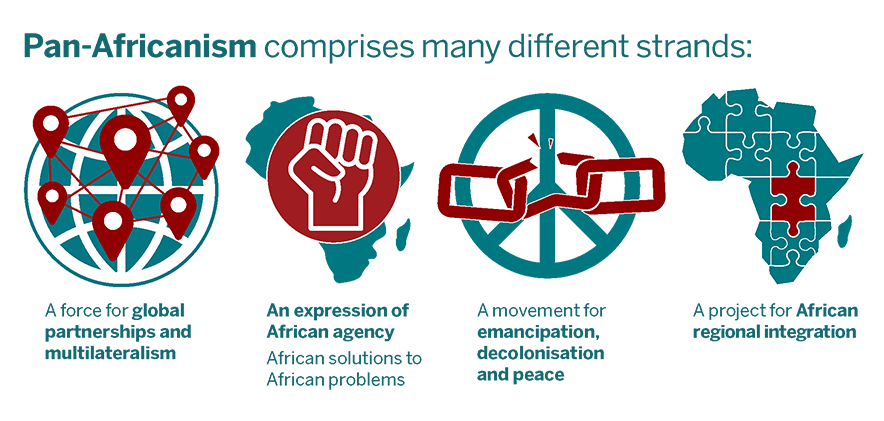

Pan-Africanism was a vital force in the decolonisation and liberation struggles of the African continent. Today, some regional integration initiatives are part of the legacy of Pan-Africanism. Nevertheless, a retreat in Pan-Africanist consciousness justifies the on-going reform of the African Union and other related platforms for African regional integration, peace and development.

This policy note is also available as a downloadable pdf External link, opens in new window..

External link, opens in new window..

Pan-Africanism is a movement, an ideology and a geopolitical project for liberating and uniting African people and the African diaspora around the world. At its heart lies the notion that through unity can be forged an independent and strengthened economic, social and political African destiny. In the words of the first president of Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah, speaking at the inaugural ceremony of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in Addis Ababa in 1963.: “We must unite in order to achieve the full liberation of our continent”.

Pan-Africanism finds resonance in the history of Nordic relations with Africa. In the 1960s, Nordic solidarity with the African liberation struggles and Nordic commitment to partnerships for self-determination and universal political rights provided fertile ground for learning from Pan-African thinking. This aspect has been echoed in the strong civil society and government support for southern African liberation struggles, through humanitarian assistance, diaspora networks and funds for education.

No longer a rallying force

Although decolonisation has been achieved – insofar as the goals of national political independence were realised in the twentieth century – the need for African unity continues to be relevant epistemologically and economically. Pan-Africanism is also – arguably – re-emerging in new ways: for instance, through cross-continental expressions of collective identity and citizen engagement. It also remains a reference point for Africans on the continent and in the diaspora. Whereas Pan-Africanism acted as a powerful rallying point for African leaders and civil society activists during the national liberation struggle, today it has very little presence in the African elite’s discourse on development.

Nevertheless, on the African continent, Pan-Africanism continues to be most influential within regional integration schemes. Regional integration has proceeded, but unevenly and at a slower pace than was planned. Pan-Africanism provided an ideological foundation for the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) and subsequently the African Union (AU). It continues to find expression in the AU’s organs and structures, such as the Pan-African Parliament, and also in AU partnership with the United Nations, the European Union and China, among others.

Grounding Pan-Africanism in Africa

The history of Pan-Africanism dates back to the mid-nineteenth century. Endeavours to institutionalise Pan-Africanism gained momentum in the early twentieth century, and the first Pan-African Congress took place in 1919, in Paris. The fifth Pan-African Congress was held in Manchester, England, in 1945, and prominent African nationalists, such as Kwame Nkrumah and Jomo Kenyatta, played a crucial role in it. This was the congress that heralded the transfer of leadership of Pan-Africanism from African Americans to Africans.

Pan-Africanism’s value as a liberation ideology was apparent as countries gained independence from colonial rule. Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah, was a prominent Pan-Africanist. On the eve and in the wake of decolonisation, he believed that colonialism would be ended once Africans were united. With such leaders, the centre of gravity for Pan-Africanism shifted from the diaspora to Africa itself. The grounding of Pan-Africanism in Africa led to the organisation of the All-African Peoples' Conference (AAPC), which was held in Accra, Ghana, after independence in 1958. This and the following AAPC conferences in the 1960s were driven by a strong conviction that African unity was critical in the struggle against colonialism, neo-colonialism and imperialism.

Even in the wake of decolonisation, there were warning signs and misgivings as to the non-viability of the new sovereign states. In most cases, these countries were constituted from colonially engineered entities, and they lacked a comprehensive sense of national belonging, such as a common language. The African elites during the early post-colonial state-building era appealed to Pan-Africanism as a uniting force – and indeed it provided a rallying point to galvanise anti-imperial agitations and nationalist aspirations during this period.

United States of Africa – the ambition lingers on

Two contending conceptualisations about the political organisation of post-colonial Africa came to define discourse on the future of the continent: Pan-Africanism as a conceptual project; and the United States of Africa as a concrete political project. At the centre of the debate was the generally acknowledged need to set up a cooperation organisation to deal with the complex social, economic, cultural and security challenges facing the emerging states. The main concerns were whether the newly independent states would survive and what role they should play in an increasingly competitive global system marked by the Cold War and East–West rivalry.

One faction of the post-colonial state leaders and African intellectuals (both on the continent and in the diaspora) supported a supra-state continental structure, ideologically founded in Pan-Africanism. This faction – the so-called Monrovia group – argued for a loose continental organisation, in which states retained their sovereignty; it advocated gradual economic integration.

The other faction, known as the Casablanca group and led by Nkrumah, espoused the more radical idea of a United States of Africa: it wanted to abolish the colonially created states and instead form one grand, supranational political organisation. Political integration in the form of federalism would ensure its functionality and survivability. Nkrumah expressed this idea in his famous statement, ‘seek ye first the political kingdom and all else shall be added unto you’. He strongly believed in political unity as an essential requirement for economic independence and development in Africa. But the United States of Africa was a political project that could only rise on the graves of nation states. And so, the Monrovia group prevailed, but the ambition of the United States of Africa has lingered on.

The AU – multinational not supranational

The victory of the moderates produced the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), launched in 1963 in Addis Ababa. Radical Pan-Africanism thus suffered a defeat and was unable to consolidate into a formidable continent-wide mass movement. Meanwhile, the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD), a continental economic development programme that expressed concern over the vanquished ideas of Pan-Africanism, was championed by such leaders as Thabo Mbeki of South Africa, Olusegun Obasanjo of Nigeria and Abdelaziz Bouteflika of Algeria. NEPAD was adopted by the OAU in 2001, and later by the AU.

The formation of the AU could be perceived as a step towards a United States of Africa. Undoubtedly, the organisation has succeeded in introducing continent-wide structures and initiatives for economic and political coordination. To some extent, it represents a move away from the restricted conception of sovereignty and inviolability, and from abuse of the principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of member states. The AU’s main mechanism for promoting peace and security – the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA), with the African Standby Force (ASF) – gives it a mandate to intervene, in collaboration with the regional economic communities (RECs), in order to resolve security issues at the national and regional level.

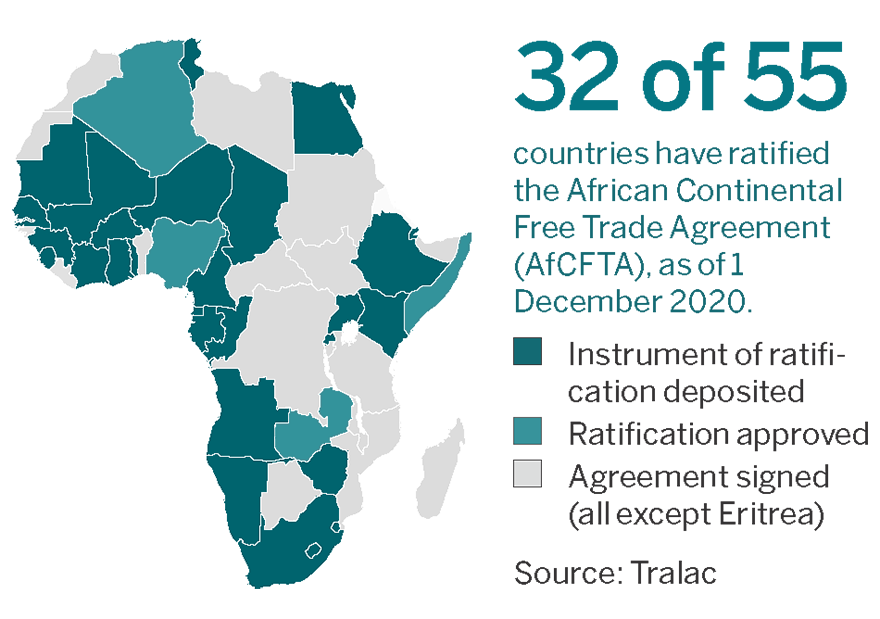

Recently, the AU launched the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) (although it is still not fully operational), which requires member states to lift tariffs from 90 per cent of goods, in order to promote free access to commodities, goods and services across the continent.

Source population statistics: World Bank 2019 for all countries except Eritrea where the latest data is from 2011.

Three-tier structure not grounded

Africa’s RECs include eight sub-regional bodies that are the building blocks of the African Economic Community, established in 1991. As five of these RECs cover the five regions of the continent, they would, together with the AU, provide Africa with an optimal three-tier governance structure – national, regional and continental. This would facilitate the aggregation of national and regional-level interests across the vast continent, and would aid negotiations and consensus building between states that differ in size, capacity and resources. However, without pooling the sovereignty of the member states through a binding formal recognition of the regional-level authority, the three-tier structure could not be institutionally grounded.

The mandates of the RECs include peace, security, development and economic integration. Their ability to fulfil such a mandate is impaired by the lack of supranational accountability and sanctions to ensure compliance by the member states. They are also impeded by the general challenge of global governance and multilateralism, in the context of competing geostrategic interests. Inadequate material and human resources, as well as deficient technological infrastructure, further limit the RECs’ ability to act. Ultimately, the willingness of member states and the international community to provide financing, mandates and space to manoeuvre will determine how the RECs deliver on their responsibilities. Ironically, this acts against the essence of AU reform, which advocates increased internal governance, accountability, organisational efficiency and independence from external financing.

Winners and losers from free trade

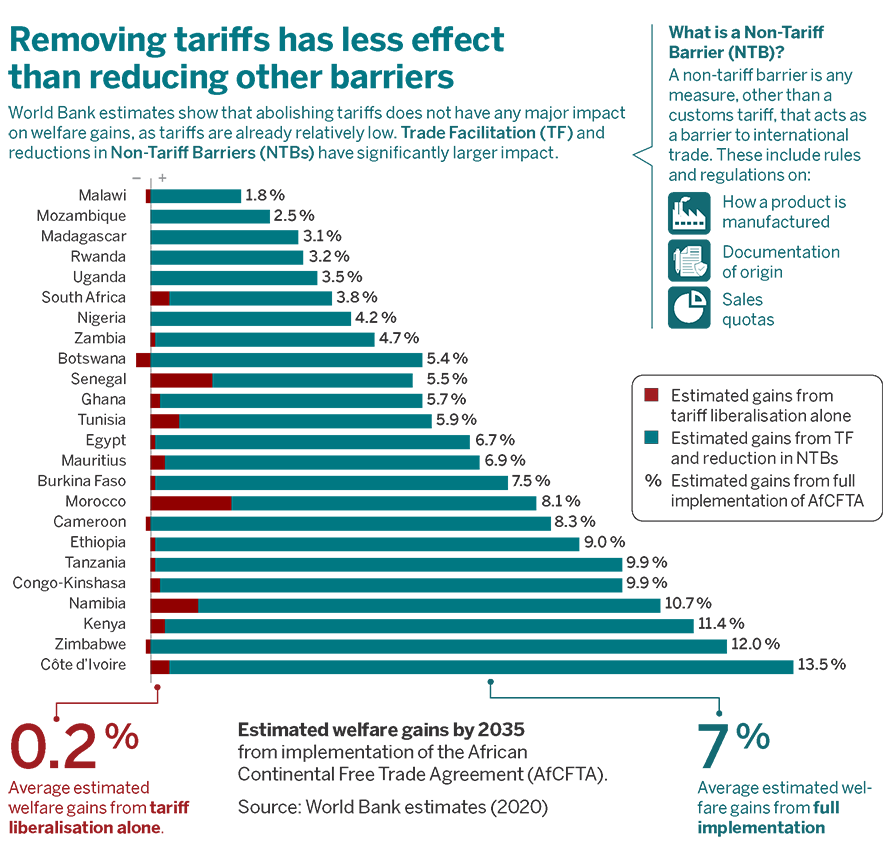

As part of AfCFTA, each REC should have established free trade and a customs union in 2017, but the work has yet to be completed. Indeed, AfCFTA itself is not yet fully operational. The removal of all intra-tariffs and reduction of non-tariff barriers will have a positive long-term impact on welfare; but there are concerns that tensions between and within countries will increase, because these reforms require national policy reforms – and those involve politically difficult choices.

There will be winners and losers. Countries that have relatively open markets will tend to benefit more from improved access to other markets. Meanwhile heavily protected economies may see a larger reallocation of output across sectors because of heightened import competition.

The transaction costs of both exporting and importing, in terms of administrative procedures, are very high across Africa. The continent’s most diversified economies and those countries with larger manufacturing bases and a more developed transport infrastructure are likely to benefit from greater economic integration. World Bank estimations External link, opens in new window. show that abolishing tariffs does not have any major impact on real income gains, as tariffs are already relatively low. For a few countries, like Botswana, Cameroon, Malawi and Zimbabwe, the impact of tariff liberalisation on real income is even estimated to be negative. Trade facilitation and reductions in non-tariff barriers have significantly larger impact. The World Bank estimates that the average welfare gain from full implementation of AfCFTA (tariff liberalisation, reduction of non-tariff barriers and trade facilitation all together) for the 24 analysed African countries will be seven per cent by 2035.

External link, opens in new window. show that abolishing tariffs does not have any major impact on real income gains, as tariffs are already relatively low. For a few countries, like Botswana, Cameroon, Malawi and Zimbabwe, the impact of tariff liberalisation on real income is even estimated to be negative. Trade facilitation and reductions in non-tariff barriers have significantly larger impact. The World Bank estimates that the average welfare gain from full implementation of AfCFTA (tariff liberalisation, reduction of non-tariff barriers and trade facilitation all together) for the 24 analysed African countries will be seven per cent by 2035.

Reducing inequality is key to integration

Significant economic disparity between and within countries makes integration more difficult. As the free trade reforms are likely to increase inequality between Africa’s states, the question is what is to be done to ensure fairness in the distribution of benefits across the countries, in order to prevent further disparities and inequality. It will be challenging to monitor the breakdown of welfare gains and losses due to AfCFTA and other policy changes that occur at the same time.

One indirect outcome of the African continental free trade agenda will be the harmonisation of other related policies by African governments, such as state policies on subsidies: the deviation between countries cannot be too large or else it will challenge the principle of fair competition on equal terms.

With their strong tradition of advocating multilateralism, free trade and international cooperation, the Nordic countries should continue to support regional integration in Africa. Drawing on their experiences of the European post-war integration projects, they could have a lot to offer, especially in the fields of education and capacity building. Correspondingly, the African and Pan-Africanist experiences of cooperation across vast cultural, social, political and economic diversities could feed into the sustainable development agenda of the Nordic countries and the international community.

NAI Policy Notes is a series of research-based briefs on relevant topics, intended for strategists, analysts and decision makers in foreign policy, aid and development. They aim to inform public debate and generate input into the sphere of policymaking. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute.