The debt trap dilemma of African governments

Balancing debt services, food security and development – while avoiding civil unrest

Khartoum, Sudan, 30 June 2022. Protesters take cover as riot police try to disperse them with a water cannon. Photo: AFP.

Nearly half of Africa’s economies are on the brink of debt distress. Unlike previous debt crises, the current one is characterised by a shift from multilateral to commercial and bilateral creditors, notably China, and the proliferation of Eurobonds. Pressured by heavy debt burdens, there is a risk that African governments divert funds from essential sectors such as education, health care and agriculture, causing a vicious cycle of stalled development, food insecurity and an elevated risk of socio-political instability.

By Assem Abu Hatab, Tabeer Riaz and Emmanuel Orkoh

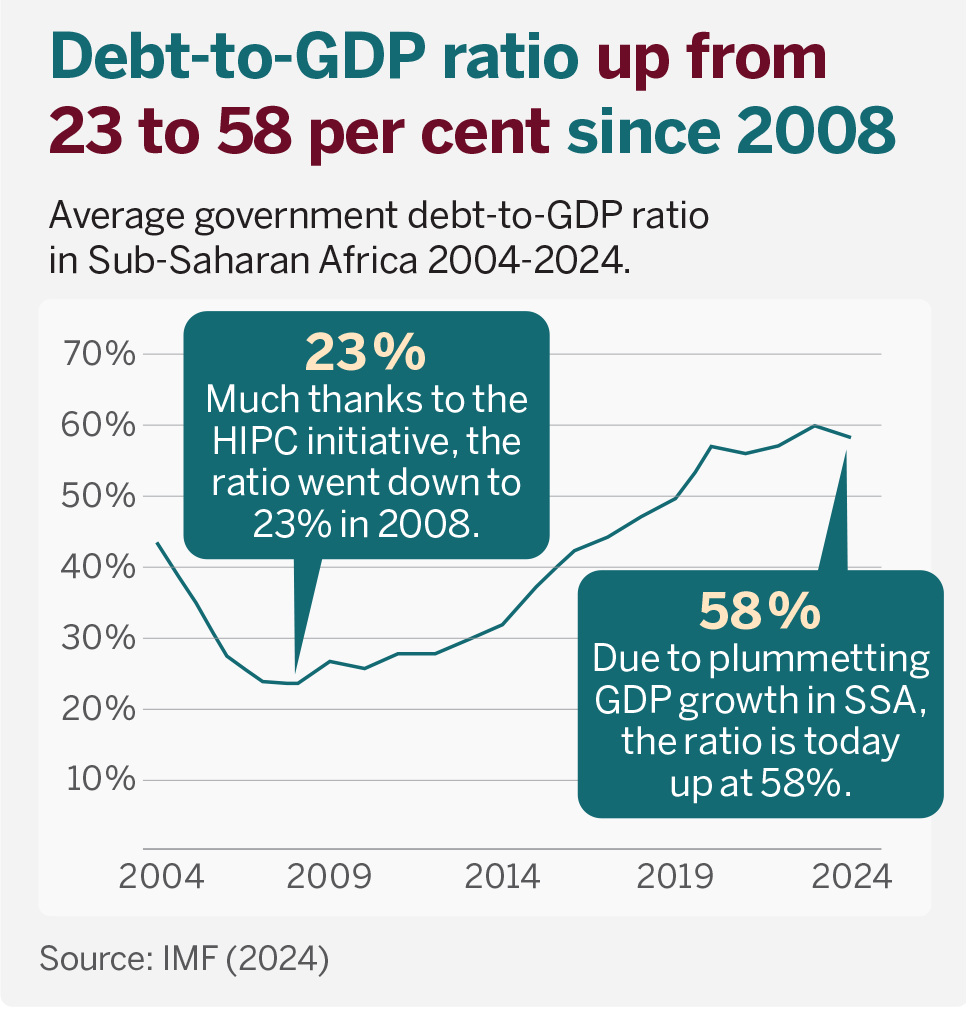

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has a long history of external debt, beginning in the 1980s when the public finances of many countries sharply declined following several external shocks. This led to a “lost decade” of low economic growth, increased poverty, food insecurity and socio-political instability. However, the implementation of debt relief under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative External link, opens in new window. and the supplementary Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI)

External link, opens in new window. and the supplementary Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI) External link, opens in new window. wiped out most of SSA’s external debts. These debt relief initiatives substantially reduced nominal public debt to sustainable levels, bringing it from a GDP-weighted average of 104 percent before their implementation to nearly 30 percent during the period from 2006 to 2011. This largely eliminated the risk of “debt overhang

External link, opens in new window. wiped out most of SSA’s external debts. These debt relief initiatives substantially reduced nominal public debt to sustainable levels, bringing it from a GDP-weighted average of 104 percent before their implementation to nearly 30 percent during the period from 2006 to 2011. This largely eliminated the risk of “debt overhang External link, opens in new window.”, reduced barriers to investment and economic growth, stabilised financial situations, and accelerated SSA’s progress towards achieving the then UN Millennium Development Goals

External link, opens in new window.”, reduced barriers to investment and economic growth, stabilised financial situations, and accelerated SSA’s progress towards achieving the then UN Millennium Development Goals External link, opens in new window., especially eradicating extreme poverty and hunger.

External link, opens in new window., especially eradicating extreme poverty and hunger.

The journey back to ballooning debts

Over the past decade, amid the repercussions of the global financial crisis in 2007-2008, which translated into high inflation in food and fuel prices, and stagnation in official development aid, posing significant challenges in mobilising domestic resources for infrastructure and socioeconomic development, many SSA countries experienced a resurgence in external debt growth. Particularly since 2013-2014, debt accumulation in SSA has risen sharply, driven by a global financial environment that encouraged borrowing due to low global interest rates, a weakened US dollar and demand-led growth in emerging markets. Debt accumulation has also been fuelled by global commodity price shocks, expanding budget deficits, diminishing real GDP growth, cumulative currency depreciations, and a broad decline in macroeconomic conditions in the majority of SSA countries. Real GDP growth in SSA fell from 6.9 percent in 2010 to 3.2 percent in 2019 (IMF, 2024b External link, opens in new window.), while public debt as a percentage of GDP soared from 28 percent to nearly 50 percent over the same period.

External link, opens in new window.), while public debt as a percentage of GDP soared from 28 percent to nearly 50 percent over the same period.

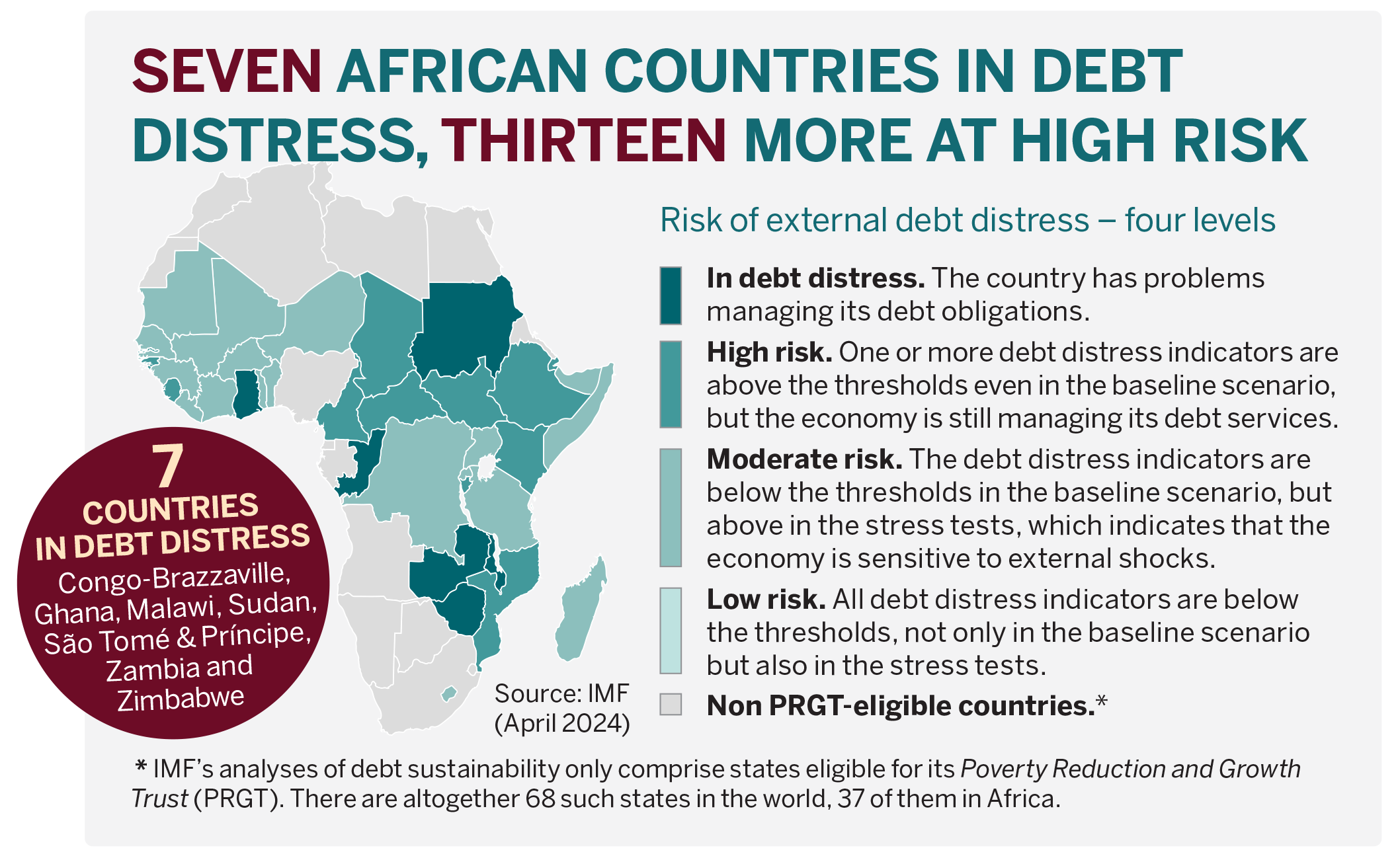

In recent years, the convergence of external shocks – notably, fragile post-Covid-19 macroeconomic conditions and the repercussions of Russian aggression in Ukraine in 2022, along with a multitude of pre-existing challenges including conflict, socioeconomic stressors and climate shocks – has strained the public finances of many SSA countries and contributed to a fresh wave of indebtedness across the region. Specifically, immediate demands for public health and stimulus expenditure, and the significant decline in tax revenues following the global economic slowdown, as well as the decrease in export earnings for resource-rich countries, have escalated debt levels by nearly 180 percent External link, opens in new window. over the past decade. This challenging situation was compounded by the US Federal Reserve’s tightening of monetary policy, along with depreciations in SSA currencies due to inflation and plummeting commodity prices, which collectively increased the cost of repaying loans and undermined the ability of many SSA countries to service their external debts. In this respect, recent International Monetary Fund (IMF) figures reveal that the average debt-to-GDP ratio for the SSA region surpassed 60 percent in 2023, with significant variations among countries; some surpassed the regional average by a considerable margin, including Cape Verde (112 percent), Zimbabwe (98 percent), Mozambique (97 percent) and Congo-Brazzaville (95 percent). Consequently, many SSA countries today find themselves at similar or even more precarious levels of indebtedness than before the HIPC Initiative and MDRI, while more than half the low-income countries in the region, per the IMF’s 2022 assessment

External link, opens in new window. over the past decade. This challenging situation was compounded by the US Federal Reserve’s tightening of monetary policy, along with depreciations in SSA currencies due to inflation and plummeting commodity prices, which collectively increased the cost of repaying loans and undermined the ability of many SSA countries to service their external debts. In this respect, recent International Monetary Fund (IMF) figures reveal that the average debt-to-GDP ratio for the SSA region surpassed 60 percent in 2023, with significant variations among countries; some surpassed the regional average by a considerable margin, including Cape Verde (112 percent), Zimbabwe (98 percent), Mozambique (97 percent) and Congo-Brazzaville (95 percent). Consequently, many SSA countries today find themselves at similar or even more precarious levels of indebtedness than before the HIPC Initiative and MDRI, while more than half the low-income countries in the region, per the IMF’s 2022 assessment External link, opens in new window., are classified as being at high risk of, or already in, debt distress.

External link, opens in new window., are classified as being at high risk of, or already in, debt distress.

Characteristics of the current debt wave

Besides the rapid growth in debt accumulation that has sounded the alarm that the region is on the brink of a devastating debt crisis, the current episode of SSA’s external debt has three distinct characteristics.

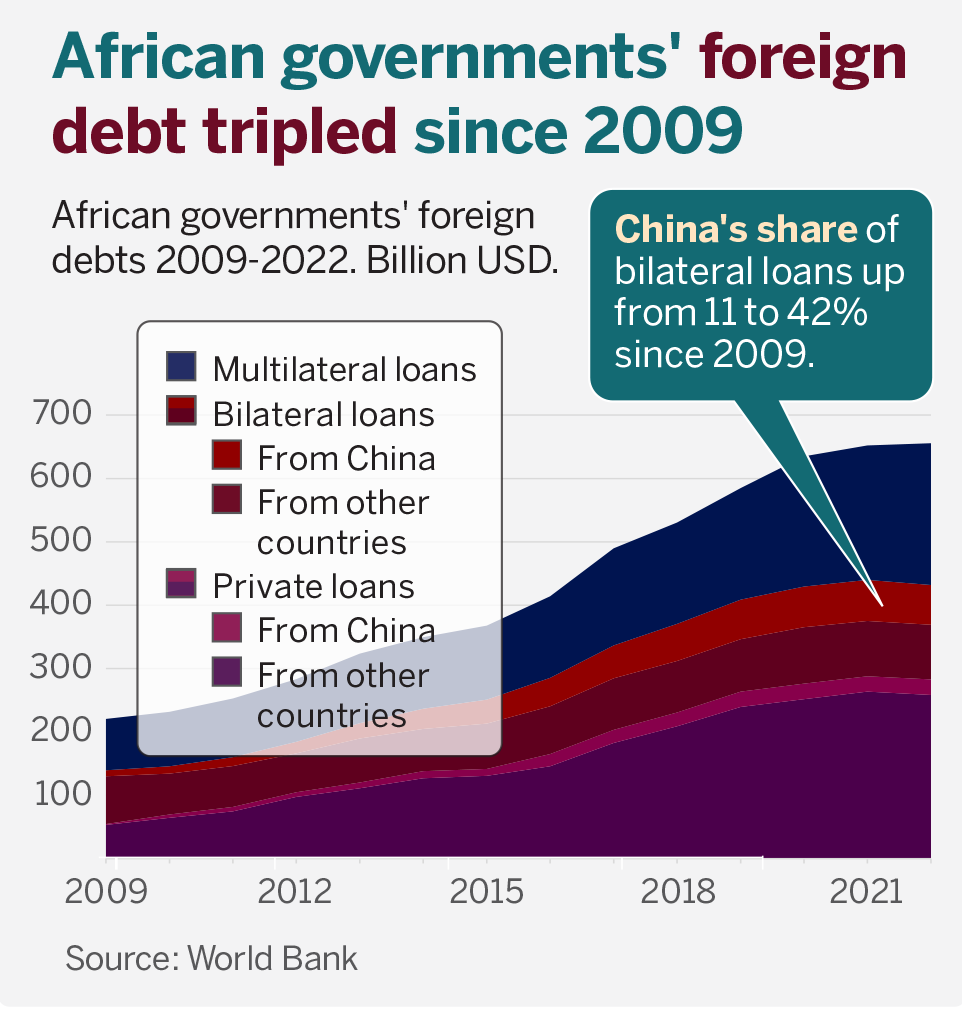

First, SSA’s external debt has traditionally been owed to multilateral institutions and creditors associated with the Paris Club External link, opens in new window., an informal group of official creditors that aims to provide coordinated and sustainable solutions for debtor countries experiencing payment difficulties. However, the current debt landscape has shifted from multilateral institutions to more expensive and short-term bilateral and commercial creditors, largely due to SSA countries entering the Eurobond market. According to World Bank data (2023)

External link, opens in new window., an informal group of official creditors that aims to provide coordinated and sustainable solutions for debtor countries experiencing payment difficulties. However, the current debt landscape has shifted from multilateral institutions to more expensive and short-term bilateral and commercial creditors, largely due to SSA countries entering the Eurobond market. According to World Bank data (2023) External link, opens in new window., multilateral creditors currently hold 23 percent of the debt, whereas bilateral creditors account for 34 percent and Eurobond debt now accounts for 44 percent of Africa’s total debt. The shift, particularly to commercial creditors, carries risks including higher interest rates and shorter repayment periods, and other less favourable lending conditions, including less flexibility during economic downturns or crises. Such increased exposure to commercial creditors could heighten vulnerability to external shocks, increase the financial burden on SSA governments and lead to debt distress, as these creditors may be less willing to provide debt relief or restructuring in times of crisis.

External link, opens in new window., multilateral creditors currently hold 23 percent of the debt, whereas bilateral creditors account for 34 percent and Eurobond debt now accounts for 44 percent of Africa’s total debt. The shift, particularly to commercial creditors, carries risks including higher interest rates and shorter repayment periods, and other less favourable lending conditions, including less flexibility during economic downturns or crises. Such increased exposure to commercial creditors could heighten vulnerability to external shocks, increase the financial burden on SSA governments and lead to debt distress, as these creditors may be less willing to provide debt relief or restructuring in times of crisis.

Second, the emergence of new players in the debt landscape of SSA, particularly China, is another marked characteristic of the region’s current external debt trends. Between 2000 and 2023, China engaged in around 1,200 loan agreements with various African governments totalling USD 160 billion External link, opens in new window.. In 2022, China emerged as Africa’s largest bilateral lender, holding nearly 12 percent, or around USD87 billion, of the continent’s public and private external debt. China has become a significant private lender, accounting for over USD24 billion of Africa’s external debt in 2022. This shift in composition of bilateral creditors introduces new dynamics and potentially divergent lending practices, which may lack transparency and adherence to international standards for debt sustainability. For instance, although the image of China as a predatory lender looking to expropriate SSA’s economic resources does not stand up to scrutiny in most cases, there are indications that China may in some cases have sought geostrategic influence in exchange for providing financial services; for example, military bases in Djibouti and Equatorial Guinea. Concerns have been raised that SSA’s increasing reliance on China for financing could increase the complexity of debt management for SSA governments, and raise concerns about the terms and conditions of loans, including interest rates, repayment periods and collateral requirements. For instance, while China has in certain cases shown flexibility by agreeing twice to restructure debt owed by Congo-Brazzaville in 2019 and in 2021, this came at a price, with increases in the net present value of repayments resulting from the restructuring. Therefore, if not carefully managed, Chinese loans to SSA could lead to debt dependency and jeopardise long-term fiscal sustainability.

External link, opens in new window.. In 2022, China emerged as Africa’s largest bilateral lender, holding nearly 12 percent, or around USD87 billion, of the continent’s public and private external debt. China has become a significant private lender, accounting for over USD24 billion of Africa’s external debt in 2022. This shift in composition of bilateral creditors introduces new dynamics and potentially divergent lending practices, which may lack transparency and adherence to international standards for debt sustainability. For instance, although the image of China as a predatory lender looking to expropriate SSA’s economic resources does not stand up to scrutiny in most cases, there are indications that China may in some cases have sought geostrategic influence in exchange for providing financial services; for example, military bases in Djibouti and Equatorial Guinea. Concerns have been raised that SSA’s increasing reliance on China for financing could increase the complexity of debt management for SSA governments, and raise concerns about the terms and conditions of loans, including interest rates, repayment periods and collateral requirements. For instance, while China has in certain cases shown flexibility by agreeing twice to restructure debt owed by Congo-Brazzaville in 2019 and in 2021, this came at a price, with increases in the net present value of repayments resulting from the restructuring. Therefore, if not carefully managed, Chinese loans to SSA could lead to debt dependency and jeopardise long-term fiscal sustainability.

Third, over the past decade, the rapid surge in Eurobond issuances alongside non-Paris Club loans with shorter maturity periods, has concentrated debt maturities between 2024 and 2030. This has positioned SSA to confront unprecedented debt service obligations in the years ahead, pushing the median public debt-to-GDP ratio from 32 percent in 2010 to around 60 percent in 2022. Zambia exemplifies these challenges. After a decade of heavy borrowing for infrastructure development, its debts surged to 131 percent of GDP in 2020, including USD3 billion in Eurobonds. In 2021, the mineral-rich country requested debt restructuring under the G20 Common Framework, which has been a complex and challenging process, given that its debt is dispersed among 44 creditors.

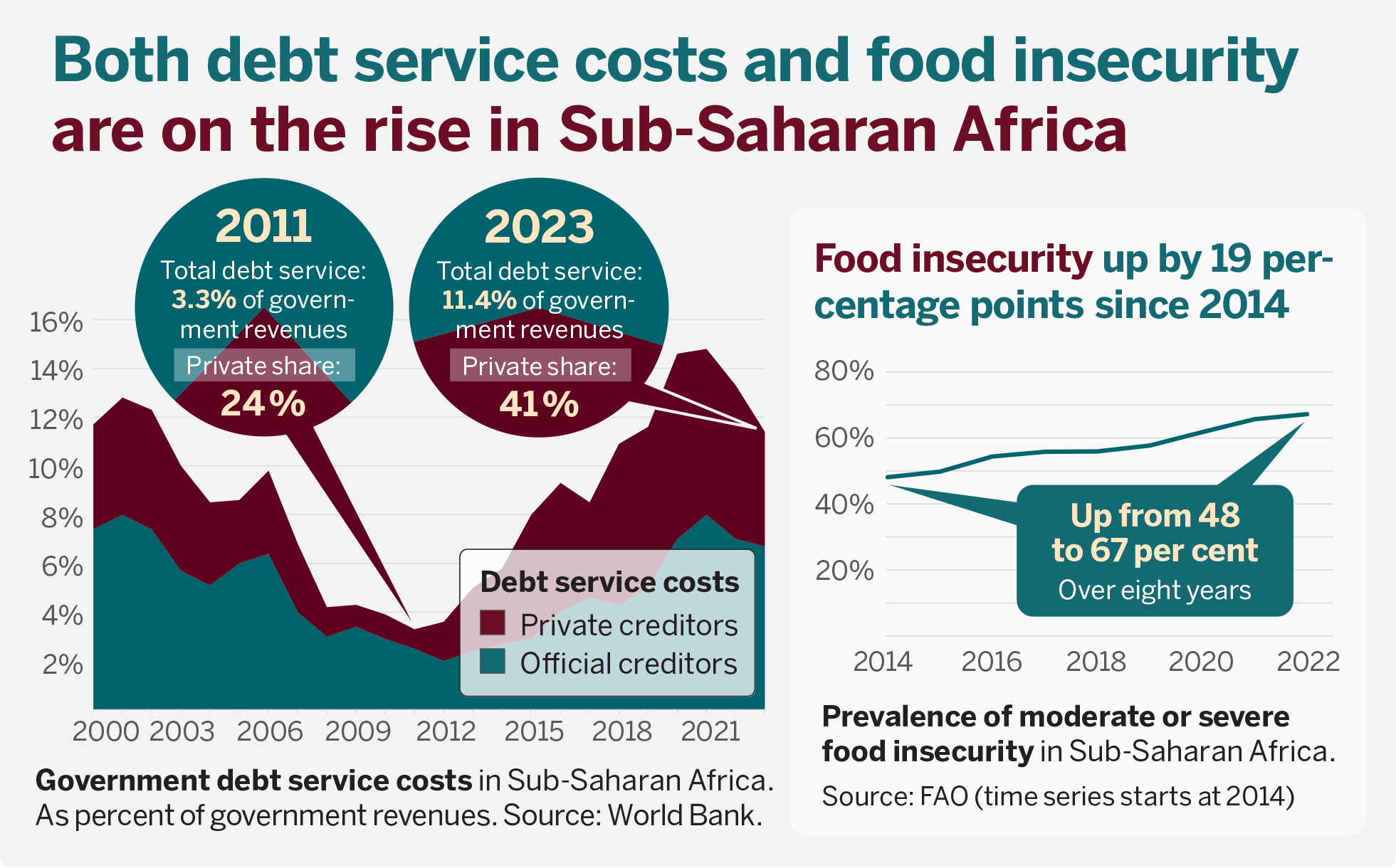

According to the African Development Bank External link, opens in new window., African countries will pay USD 74 billion in debt service payments in 2024, a sharp increase from USD17 billion in 2010. According to World Bank data (2023)

External link, opens in new window., African countries will pay USD 74 billion in debt service payments in 2024, a sharp increase from USD17 billion in 2010. According to World Bank data (2023) External link, opens in new window., at least a fifth of government revenue in the SSA region goes on external debt payments, which largely exceeds governments’ expenditure on education and health care. Therefore, many SSA countries that are in debt distress do not necessarily have high debt stocks, but their capacity to service their debts is challenged by elevated current costs of funding in tight financial conditions. The disproportionate allocation of funds for debt servicing raises grave concerns, given SSA countries’ limited capacity to generate the requisite budgetary resources to cope with the rapid surge in debt servicing. This diversion of resources away from critical social sectors also perpetuates cycles of poverty and inequality that may hinder progress towards achieving the targets of the Sustainable Development Goals in the region.

External link, opens in new window., at least a fifth of government revenue in the SSA region goes on external debt payments, which largely exceeds governments’ expenditure on education and health care. Therefore, many SSA countries that are in debt distress do not necessarily have high debt stocks, but their capacity to service their debts is challenged by elevated current costs of funding in tight financial conditions. The disproportionate allocation of funds for debt servicing raises grave concerns, given SSA countries’ limited capacity to generate the requisite budgetary resources to cope with the rapid surge in debt servicing. This diversion of resources away from critical social sectors also perpetuates cycles of poverty and inequality that may hinder progress towards achieving the targets of the Sustainable Development Goals in the region.

Growing debts spark food insecurity

This confluence of unsustainable debt levels, along with recent global shocks, has profound implications for the food security of the SSA region, which is already grappling with hunger and malnutrition. At a time of elevated global food prices and volatile supply chains, unsustainable debt levels intensify pressure on food production and distribution systems, drive up food prices, and exacerbate hunger and malnutrition; in SSA most countries are heavily dependent on food imports External link, opens in new window. and 60 percent of the population are already experiencing moderate to severe food insecurity. The economics literature might suggest that food insecurity is more closely correlated with a country’s income level than its debt-to-GDP ratio, but new evidence from Nordic Africa Institute research suggests that external debt stock and debt servicing generally exert a significant negative impact on food security in SSA, with few exceptions.

External link, opens in new window. and 60 percent of the population are already experiencing moderate to severe food insecurity. The economics literature might suggest that food insecurity is more closely correlated with a country’s income level than its debt-to-GDP ratio, but new evidence from Nordic Africa Institute research suggests that external debt stock and debt servicing generally exert a significant negative impact on food security in SSA, with few exceptions.

Among the many pathways by which unsustainable debt levels cause food insecurity, four are especially relevant to SSA. First, unsustainable levels of external debt lead to macroeconomic instability, including currency depreciation and inflation. These make importing agricultural inputs such as fertilisers and machinery unaffordable for producers, leading directly and indirectly to lower agricultural productivity and decreased food availability. Second, unsustainable debt levels fuel inflation and exchange rate fluctuations, which erode the purchasing power of the population and complicate household budgets; nearly 50 percent of household expenditure in SSA is allocated to food commodities. Third, this increases both the demand for and the cost of food imports for a region that is a net importer of food and agricultural products (despite having 60 percent of the world’s uncultivated and unutilised arable land). Accordingly, under the dynamics of rapid indebtment, Africa’s food import bill has more than tripled, reaching about USD 35 billion a year; food prices rose, on average, nearly 24 percent External link, opens in new window. between 2020 and 2022. Four, the impact of external debt on food security extends well beyond mere shortages and affordability, potentially igniting socio-political unrest. Empirical agricultural economics literature indicates that food insecurity is often compounded by and intertwined with conflict, creating a vicious cycle whereby food insecurity is both a trigger for and a consequence of unrest. A recent example is Sri Lanka, where a government default on debt led to an economic crisis, resulting in a staggering 90 percent increase in food prices. This left over a quarter of the population facing severe food insecurity, contributing to mass revolts that toppled the political system. Many signs of the debt-food security links discussed above suggest that the Sri Lanka scenario could potentially unfold in several SSA countries with similar external vulnerabilities, particularly those where external sectors are also under intense pressure.

External link, opens in new window. between 2020 and 2022. Four, the impact of external debt on food security extends well beyond mere shortages and affordability, potentially igniting socio-political unrest. Empirical agricultural economics literature indicates that food insecurity is often compounded by and intertwined with conflict, creating a vicious cycle whereby food insecurity is both a trigger for and a consequence of unrest. A recent example is Sri Lanka, where a government default on debt led to an economic crisis, resulting in a staggering 90 percent increase in food prices. This left over a quarter of the population facing severe food insecurity, contributing to mass revolts that toppled the political system. Many signs of the debt-food security links discussed above suggest that the Sri Lanka scenario could potentially unfold in several SSA countries with similar external vulnerabilities, particularly those where external sectors are also under intense pressure.

The increasing pressure from external debts compels SSA governments to prioritise debt servicing over investments in agriculture and food production. As funding diminishes for essential agricultural development programmes, such as irrigation projects and subsidies for smallholder farmers, food productivity and availability are adversely affected. This trend is reflected in the persistent decline of the average share of agriculture in total government expenditure in Africa, which has dropped from about 7 percent per year in the 1980s to less than 3 percent per year in the past decade. In the same vein, only seven out of 54 African countries meet the 10 percent threshold set by the Maputo Declaration External link, opens in new window. in 2013, and only 12 countries have fulfilled the commitment to invest 1 percent of GDP in agricultural research and development. This underinvestment hampers agricultural innovation and productivity, exacerbating food insecurity and malnutrition across the continent.

External link, opens in new window. in 2013, and only 12 countries have fulfilled the commitment to invest 1 percent of GDP in agricultural research and development. This underinvestment hampers agricultural innovation and productivity, exacerbating food insecurity and malnutrition across the continent.

SSA governments facing high debt-servicing obligations often resort to austerity measures External link, opens in new window., which typically include cuts to social programmes such as food assistance and nutrition initiatives. Such austerity-driven cuts in food assistance programmes can lead to increased malnutrition, particularly among vulnerable populations such as children, pregnant women and older people. In addition, tight austerity measures may force governments to halt long-term infrastructure development projects before their completion, ultimately undermining potential return on investment and hindering economic growth. An example is Angola, which has recently frozen a portion of non-social spending (i.e. government expenditures that are not directly related to social services, food assistance and nutrition programmes, and healthcare or welfare programmes) on projects that are less than 80 percent complete, to manage to continue servicing debt, paying salaries and making sure the country is functioning.

External link, opens in new window., which typically include cuts to social programmes such as food assistance and nutrition initiatives. Such austerity-driven cuts in food assistance programmes can lead to increased malnutrition, particularly among vulnerable populations such as children, pregnant women and older people. In addition, tight austerity measures may force governments to halt long-term infrastructure development projects before their completion, ultimately undermining potential return on investment and hindering economic growth. An example is Angola, which has recently frozen a portion of non-social spending (i.e. government expenditures that are not directly related to social services, food assistance and nutrition programmes, and healthcare or welfare programmes) on projects that are less than 80 percent complete, to manage to continue servicing debt, paying salaries and making sure the country is functioning.

In a region where undernourishment has risen over the past decade – from 17 percent in 2011 to 22 percent in recent years External link, opens in new window., the highest percentage of any region in the world – austerity-driven cuts in food assistance and nutrition programmes mean that many individuals lose access to crucial food support that helps them meet their basic dietary needs. This can lead to increased malnutrition, which undermines efforts to improve food security and nutrition, and deepen the cycle of poverty and health disparities in the region. In this regard, the empirical development economics literature suggests that the relationship between external debt and food security is bidirectional, implying not only that high external debt contributes to food insecurity, but also that food insecurity drives the demand for external debt. Persistent food insecurity compels SSA governments to seek external debt to fund emergency food imports, social safety nets, and nutrition programmes to address immediate needs, or to invest in agricultural development and infrastructure to boost food production in the long term. Thus, the interplay between external debt and food security creates a vicious cycle, where each exacerbates the other, making it challenging for SSA countries to achieve sustainable economic growth and food security.

External link, opens in new window., the highest percentage of any region in the world – austerity-driven cuts in food assistance and nutrition programmes mean that many individuals lose access to crucial food support that helps them meet their basic dietary needs. This can lead to increased malnutrition, which undermines efforts to improve food security and nutrition, and deepen the cycle of poverty and health disparities in the region. In this regard, the empirical development economics literature suggests that the relationship between external debt and food security is bidirectional, implying not only that high external debt contributes to food insecurity, but also that food insecurity drives the demand for external debt. Persistent food insecurity compels SSA governments to seek external debt to fund emergency food imports, social safety nets, and nutrition programmes to address immediate needs, or to invest in agricultural development and infrastructure to boost food production in the long term. Thus, the interplay between external debt and food security creates a vicious cycle, where each exacerbates the other, making it challenging for SSA countries to achieve sustainable economic growth and food security.

Policy recommendations

Breaking the link between external debt and food insecurity in Africa requires urgent action and close international coordination across key policy areas for both debt and food security.

- SSA governments should reform financial and monetary policies to improve their institutional budgeting and risk management frameworks. This will help them efficiently assess fiscal risks and manage the changing structures of their debt portfolios. Such adjustments should also be designed to improve control over government expenditure to ensure that borrowed funds are efficiently invested in growth-enhancing projects that promote economic growth and generate income for debt repayment.

- Lenders should collaborate in negotiations to explore and evaluate ways to assist SSA countries in addressing their complex debt situation. Potential measures include initiatives akin to the G20-backed Debt Service Suspension Initiative

External link, opens in new window., rescue loans from the IMF and other debt relief initiatives, which often require shareholder approval or favourable assessments by multilateral development banks before entering into debt rescheduling negotiations.

External link, opens in new window., rescue loans from the IMF and other debt relief initiatives, which often require shareholder approval or favourable assessments by multilateral development banks before entering into debt rescheduling negotiations. - Regional financial integration, through initiatives such as the African Continental Free Trade Agreement, offers promising opportunities to enhance domestic resource mobilisation and ensure debt sustainability.

- SSA governments should, in collaboration with the international community and civil society organisations, identify and offer support to vulnerable households facing food insecurity due to austerity measures and expenditure cuts to reduce fiscal deficits.

- It is necessary to prioritise investments in sustainable agriculture to build the productive capacities of SSA food systems and foster food security, building their preparedness and adaptive capacity for future and potential risks.

NAI Policy Notes is a series of research-based briefs on relevant topics, intended for strategists and decision makers in foreign policy, aid and development. It aims to inform and generate input to the public debate and to policymaking. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute. The quality of the series is assured by internal peer-reviewing processes.

About the authors

- Assem Abu Hatab is professor in development economics, and senior researcher at NAI, with a specific focus on the economics and sustainable management of food systems.

- Tabeer Riaz is an agricultural economist, and research assistant at NAI, with a focus on water management.

- Emmanuel Orkoh is a development economist and postdoctoral researcher at NAI. His research focuses on the impact of trade and welfare policies in Africa.

How to refer to this policy note:

Abu Hatab, Assem; Riaz, Tabeer; Orkoh, Emmanuel (2024). The debt trap dilemma of African governments : Balancing debt services, food security and development – while avoiding civil unrest. (NAI Policy Notes, 2024:3). Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:nai:diva-2961 External link, opens in new window.

External link, opens in new window.