Yesterday mineral supplier, tomorrow battery producer

How green industrialisation can push Africa's economies up the global value chains

Mining in Zambia, October 2006. Photo: Kyle Gman, Flickr.

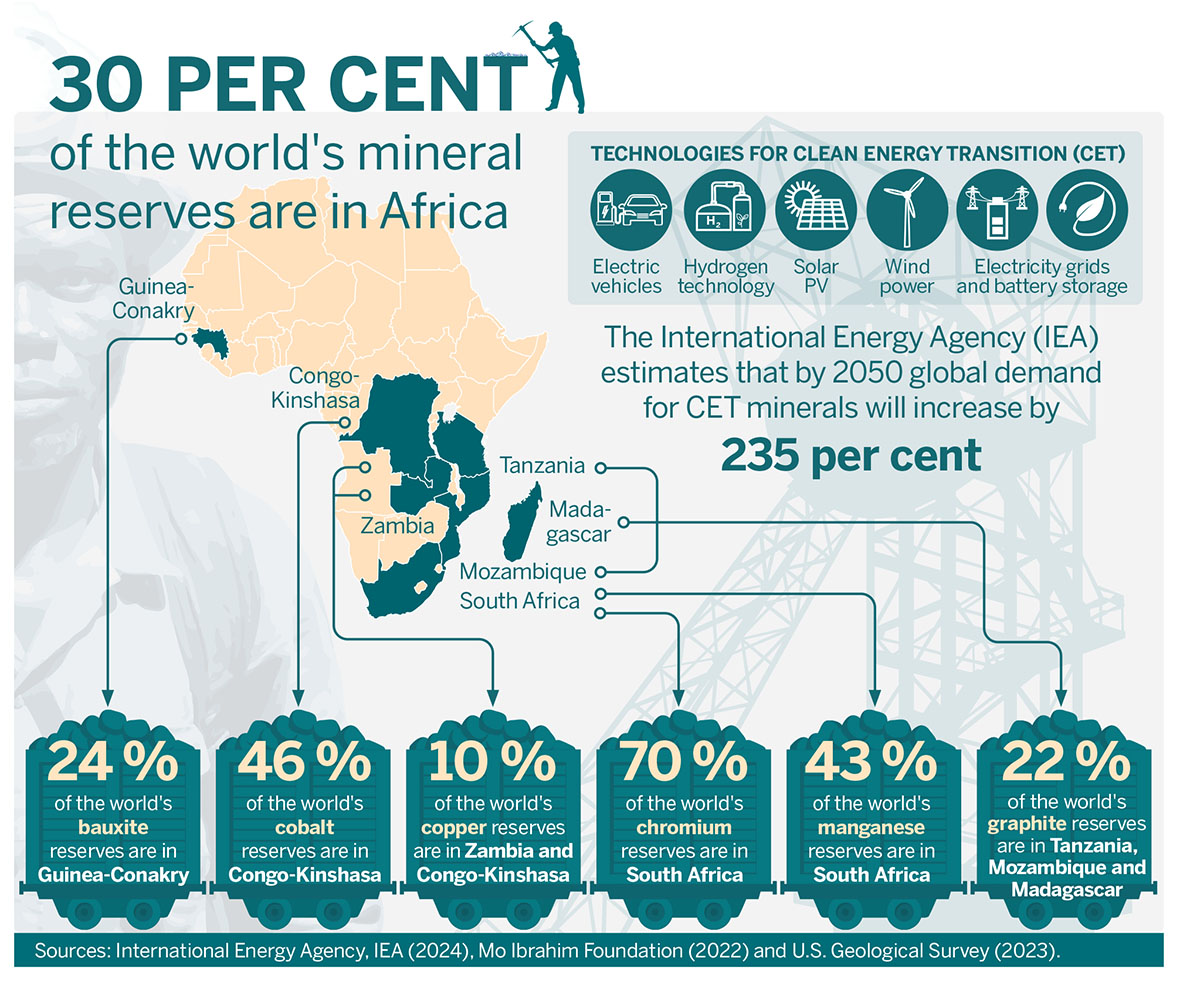

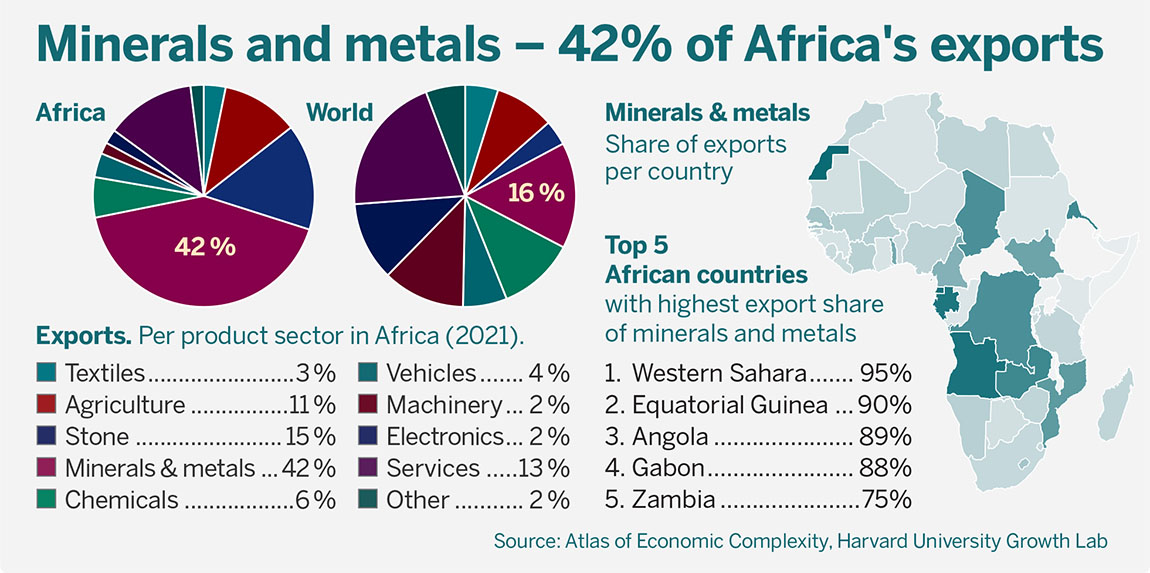

The current global green mineral boom is driving increased mining exploration in Africa. The African Union has outlined shared visions to leverage the continent’s mineral reserves and youth boom in pursuit of sustainable development and socio-economic transformation. Achieving these goals requires mineral-rich African economies to transition from commodity export to manufacture of higher value-added products. To do so, they need to invest in their youthful population, and in research and innovation.

The global commodities boom that began in the early 2000s has been driven by rising demand from emerging markets, particularly China and India. While oil and gas have long dominated the geoeconomic agenda for extractive resources, the shift towards renewable energy, electrification and digitalisation has meant increased demand for battery minerals (cobalt, bauxite, platinum, graphite, nickel, manganese, lithium, rare earths) and for copper and gold, used in electrical wiring and circuit boards. These structural shifts on the demand side are accompanied by increased mineral exploration and new mining developments in Africa. Resource-rich African countries provide commodities needed for the green transition; but they bear the disproportionate environmental and social costs of extraction and derive little benefit from it.

Calls have arisen for better conditions in African mining – especially for fair agreements on revenue sharing between multinational firms and governments, and for increased ‘local content’ (the share of goods and services provided in the sector domestically). These issues shape local, national and international political debate, and have sometimes been criticised as a form of ‘resource nationalism’. African countries are becoming increasingly proactive in aligning and shaping policies. Importantly, in 2009 African grassroots activists pushed the African Union (AU) to implement the Africa Mining Vision, which now frames the strategic direction of the continent’s minerals sector and seeks to make Africa’s minerals part of its socio-economic transformation. At the centre of the strategy is value addition. In recent years, DR Congo, Guinea, Tanzania and other African countries have renegotiated the terms of large-scale mineral investment in their countries to gain better deals, promoting local and regional mineral value chains.

The changing African mining agenda

Minerals are primary inputs in long manufacturing value chains. African countries can benefit from these chains and reduce dependence on commodity exports, as highlighted in a recent European Centre for Development Policy Management report External link, opens in new window. (2023) on the potential for green industrial development in Africa. In a world where Asia, North America and Europe dominate the more lucrative end of battery-mineral value chain (e.g. the refining of minerals and assembly of battery packs), research and development and assembly of electric cars, resource-rich African countries are all too aware of their position in the global value chain: they are seeking to have mining feature on their development agendas and to shape their technological futures on their own terms.

External link, opens in new window. (2023) on the potential for green industrial development in Africa. In a world where Asia, North America and Europe dominate the more lucrative end of battery-mineral value chain (e.g. the refining of minerals and assembly of battery packs), research and development and assembly of electric cars, resource-rich African countries are all too aware of their position in the global value chain: they are seeking to have mining feature on their development agendas and to shape their technological futures on their own terms.

Across the continent, for example in Mali, Burkina Faso and Tanzania, there are plans to set up new refineries to process minerals such as gold or nickel. Namibia and Zimbabwe has put a legislation in place to cover domestic processing of lithium. South Africa has adopted green energy transition plans on the back of its abundant platinum-group minerals. Notably, DR Congo and Zambia, which are Africa’s lead cobalt and copper producers are partnering to establish a battery industry. They are being supported in these plans by the African Minerals Development Centre which was established in 2013 to drive the African Mining Vision. Additionally, start-ups in electrical vehicle assembly are emerging across the continent in Ghana, Nigeria and Kenya, so too the growth of renewable energy projects and digital technology hubs External link, opens in new window..

External link, opens in new window..

The AfCFTA provides renewed opportunities for the deeper and more sustainable integration of African economies. A key challenge for Africa’s resource-rich countries is how to implement policies for value addition that consider not only the large-scale mining sector, where multinational corporations dominate, but also the role of small-scale mining, which often raises ethical concerns on work conditions but sees greater local ownership and employment. To this end countries such as DR Congo, Tanzania and Zambia are innovating on models to integrate both. For example, they are promoting small-scale mining cooperatives to provide financial and technical support to scale-up, mechanise and establish safe work and environmental guidelines. More recently, in line with industrialisation agendas, small-scale mining cooperatives offer a way to aggregate mineral produce for domestic refining and manufacturing. However, challenges related to the governance of mining, and collection of resource rents remain.

Social and environmental challenges

While mining often lies at the heart of programmes to boost exports and industrial production in Africa, its adverse environmental and social impact is widely acknowledged and has led to much controversy and litigation. In Zambia, for example, mining communities won a court case External link, opens in new window. on environmental pollution against the multinational mining company Vedanta, setting a legal precedent. At small-scale mining sites, dangerous working conditions, child labour and the lack of formalised governance have fuelled conflict and raised ethical concerns.

External link, opens in new window. on environmental pollution against the multinational mining company Vedanta, setting a legal precedent. At small-scale mining sites, dangerous working conditions, child labour and the lack of formalised governance have fuelled conflict and raised ethical concerns.

In contexts where the regulatory capacity is weak, ensuring socially and environmentally sustainable mining becomes challenging. In some African countries, civil society has mobilised to halt mining – e.g. ongoing efforts to stop a titanium mine External link, opens in new window. being developed in Mpondoland on South Africa’s east coast or the cancellation in 2023 of plans to mine

External link, opens in new window. being developed in Mpondoland on South Africa’s east coast or the cancellation in 2023 of plans to mine External link, opens in new window. in Zambia’s lower Zambezi conservation area, following a decade of environmental action. In several instances, communities have moved into small-scale mining, seeing it as a way for them to benefit directly from booming demand. In the Katanga region of DR Congo, for example, the liberalisation in the early 2000s of the previously dominant (but financially distressed) state mining sector saw a surge in small-scale mining

External link, opens in new window. in Zambia’s lower Zambezi conservation area, following a decade of environmental action. In several instances, communities have moved into small-scale mining, seeing it as a way for them to benefit directly from booming demand. In the Katanga region of DR Congo, for example, the liberalisation in the early 2000s of the previously dominant (but financially distressed) state mining sector saw a surge in small-scale mining External link, opens in new window. on the back of large labour retrenchment, and an attendant rise in new investment in mining from multinationals.

External link, opens in new window. on the back of large labour retrenchment, and an attendant rise in new investment in mining from multinationals.

However, investments in large-scale mining from multinational corporations have also seen concerns raised on corruption and tax evasion and calls for greater transparency in the mineral agreements that countries enter. This has brought about some change. Frameworks have been established for high-level negotiations between governments and foreign investors to address issues of tax evasion and corruption. The global campaign “Publish what you pay External link, opens in new window.”, organised by NGOs such as Global Witness, Mining Watch, Public Eye and various small national organisations (over 400, in 28 countries), has made strides on tax evasion and avoidance. On the back of this international public pressure, the intergovernmental Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative

External link, opens in new window.”, organised by NGOs such as Global Witness, Mining Watch, Public Eye and various small national organisations (over 400, in 28 countries), has made strides on tax evasion and avoidance. On the back of this international public pressure, the intergovernmental Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative External link, opens in new window. (EITI) was established in 2003 to promote transparent governance of natural resources by encouraging its 57 member states (27 of them African) to disclose mining-related fiscal data regularly. The requirements for obtaining mining rights for large-scale mine developments have grown more rigorous and standardised. Today, preliminary environmental impact assessments are a prerequisite in most African countries. In many places, mining investors are also required to negotiate with resident communities to obtain “social licences” and commit to remediation procedures after mine closure. However, the behaviour of mining investors varies according to the different legislation in host countries. Furthermore, most action aimed at addressing local concerns on the benefits of mining and minimising negative impacts – from corporate social responsibility (CSR) programmes to environmental audits – still relies heavily on voluntary commitment to non-binding standards.

External link, opens in new window. (EITI) was established in 2003 to promote transparent governance of natural resources by encouraging its 57 member states (27 of them African) to disclose mining-related fiscal data regularly. The requirements for obtaining mining rights for large-scale mine developments have grown more rigorous and standardised. Today, preliminary environmental impact assessments are a prerequisite in most African countries. In many places, mining investors are also required to negotiate with resident communities to obtain “social licences” and commit to remediation procedures after mine closure. However, the behaviour of mining investors varies according to the different legislation in host countries. Furthermore, most action aimed at addressing local concerns on the benefits of mining and minimising negative impacts – from corporate social responsibility (CSR) programmes to environmental audits – still relies heavily on voluntary commitment to non-binding standards.

Small-scale mining contributes to the global supply of green transition minerals such as copper, cobalt, lithium and manganese. Also, for digitalisation, with demand for minerals such gold, and the so-called 3Ts (tantalum, tungsten and tin), some that are sourced from conflict-ridden areas such as Eastern DR Congo. While most mining-related conflict remains confined to a local context, the increased scrutiny of mining operations in source countries also affects international trade. “Due diligence” procedures – like those codified by the OECD External link, opens in new window. that require companies which import minerals to identify, report and address possible rights violations and adverse impacts all along the value chain – have become more stringent. In some cases, they have been made compulsory and incorporated into legislation. One example is the US Dodd–Frank Act

External link, opens in new window. that require companies which import minerals to identify, report and address possible rights violations and adverse impacts all along the value chain – have become more stringent. In some cases, they have been made compulsory and incorporated into legislation. One example is the US Dodd–Frank Act External link, opens in new window. (2010), which has a section with import requirements regarding conflict minerals originating from DR Congo and adjoining countries. Another is the EU Regulation 2017/821

External link, opens in new window. (2010), which has a section with import requirements regarding conflict minerals originating from DR Congo and adjoining countries. Another is the EU Regulation 2017/821 External link, opens in new window. for responsible trade in minerals from high-risk areas. More recently, in 2023, with the increased demand for battery minerals for the green transition, the EU plans to adopt certification for batteries, the EU battery passport

External link, opens in new window. for responsible trade in minerals from high-risk areas. More recently, in 2023, with the increased demand for battery minerals for the green transition, the EU plans to adopt certification for batteries, the EU battery passport External link, opens in new window., aimed at creating a regulatory standard in the life cycle of batteries. While laudable, these regulatory mechanisms have been criticised for their failure to acknowledge the significance of small-scale mining for the livelihood of millions of Africans.

External link, opens in new window., aimed at creating a regulatory standard in the life cycle of batteries. While laudable, these regulatory mechanisms have been criticised for their failure to acknowledge the significance of small-scale mining for the livelihood of millions of Africans.

To address some of these challenges, African countries will need to ensure that global regulatory frameworks align to their develop agendas, and to shape their own benchmarks (especially in extractive locations), to which the state and corporations need to adhere. This will require a shift from voluntary CSR to binding agreements. Additionally, across several African countries there are calls to engage with debates on the redistribution and management of resource rents from large-scale mining, especially given the strategic significance of green minerals.

A green transformation agenda

Minerals for the green transition, with which southern and central Africa are particularly endowed, are seen as strategic in Africa’s socio-economic transformation agenda. However, huge deposits of mineral resources offer no guarantee of prosperity and shared benefits External link, opens in new window.. In Sub-Saharan Africa, only Botswana has achieved sustained development by harnessing its natural resources. Several challenges prevent many of Africa’s commodity-dependent economies from embarking on a green transformation agenda. The combination of commodity price shocks and lack of fiscal discipline brings macroeconomic instability, which manifests itself in high inflation, large budget deficits, high indebtedness and capital flight. Moreover, less democratic regimes in countries that are rich in natural resources are more prone to rent-seeking behaviour (i.e. privileged elites exploiting their positions to extract private benefits from public resources). This hits public spending efficiency and contributes to poor governance, political instability and conflict. Instability and mismanagement present obstacles to the diversification and industrialisation of the economy, as a risky environment is off-putting to domestic and foreign investors alike. In addition, resource-rich countries tend to perform poorly in terms of human capital development: opportunities are missed, as people living in poverty do not get a fair chance because they suffer from poor healthcare, underemployment and low-quality education (or no schooling at all).

External link, opens in new window.. In Sub-Saharan Africa, only Botswana has achieved sustained development by harnessing its natural resources. Several challenges prevent many of Africa’s commodity-dependent economies from embarking on a green transformation agenda. The combination of commodity price shocks and lack of fiscal discipline brings macroeconomic instability, which manifests itself in high inflation, large budget deficits, high indebtedness and capital flight. Moreover, less democratic regimes in countries that are rich in natural resources are more prone to rent-seeking behaviour (i.e. privileged elites exploiting their positions to extract private benefits from public resources). This hits public spending efficiency and contributes to poor governance, political instability and conflict. Instability and mismanagement present obstacles to the diversification and industrialisation of the economy, as a risky environment is off-putting to domestic and foreign investors alike. In addition, resource-rich countries tend to perform poorly in terms of human capital development: opportunities are missed, as people living in poverty do not get a fair chance because they suffer from poor healthcare, underemployment and low-quality education (or no schooling at all).

Investment in reproducible capital

Green growth requires substantial physical and human capital. Since mineral resources are finite, resource rents will diminish over time and ultimately be exhausted. Mineral-rich African countries need to transform their resources into reproducible assets: i.e. use the government share of profits to invest in physical and human capital. Some resource-abundant countries, like Zambia, Nigeria, Gabon and Botswana, have been relatively successful External link, opens in new window. in this. Botswana, for example, has a fairly transparent fiscal system

External link, opens in new window. in this. Botswana, for example, has a fairly transparent fiscal system External link, opens in new window. and allocates resources efficiently from mining to public services (like education and health) and infrastructure (such as energy, water). Others, such as Angola and Congo-Brazzaville – though possessing significant resource rents – are running down their assets, which will reduce future social welfare.

External link, opens in new window. and allocates resources efficiently from mining to public services (like education and health) and infrastructure (such as energy, water). Others, such as Angola and Congo-Brazzaville – though possessing significant resource rents – are running down their assets, which will reduce future social welfare.

Regarding small-scale mining, it is no longer viewed as an illegal activity that should be banned, but as a sector that should be formalised, scaled up and supported to provide decent employment and sustainable livelihoods. The Mosi-oa-Tunya Declaration (2018) in Livingstone, Zambia, reflects this shift by acknowledging the greater local participation, ownership and direct community benefits of the sector, compared to large-scale industrial mining. However, the different approaches taken to small-scale mining can result in the uneven distribution of benefits across territories and social/economic categories. While several initiatives to upskill small-scale miners in areas such as health and safety External link, opens in new window., mining techniques

External link, opens in new window., mining techniques External link, opens in new window. and geological surveys

External link, opens in new window. and geological surveys External link, opens in new window. have borne interesting results, there is a continuing urgent need for additional support and investment. Affordable credit to purchase equipment for mining and processing remains an issue, even when small-scale miners can pool resources through mining cooperatives. Access to reliable electricity to operate equipment, let alone energy for refining of minerals and their production into finished goods is needed but hampered by the large energy deficits in most African countries. Inadequate transport and logistics related to the moving and storage of mineral commodities disproportionately affects small-scale miners, who often must rely on brokers who at times skim much of the value of what they produce. Additionally, miners and their communities continue to face multiple health and safety risks. A significant share of the workforce in small-scale mining are women. Unequal pay, sexual harassment and difficulties to obtain mining titles constrain women’s decent work outcomes. To support decent work in small-scale mining, the World Bank (2020) report on the sector also recommends interventions that target health and improve wellbeing. Provision of quality education would also importantly provide the base to catalyse innovation for higher added value products from minerals.

External link, opens in new window. have borne interesting results, there is a continuing urgent need for additional support and investment. Affordable credit to purchase equipment for mining and processing remains an issue, even when small-scale miners can pool resources through mining cooperatives. Access to reliable electricity to operate equipment, let alone energy for refining of minerals and their production into finished goods is needed but hampered by the large energy deficits in most African countries. Inadequate transport and logistics related to the moving and storage of mineral commodities disproportionately affects small-scale miners, who often must rely on brokers who at times skim much of the value of what they produce. Additionally, miners and their communities continue to face multiple health and safety risks. A significant share of the workforce in small-scale mining are women. Unequal pay, sexual harassment and difficulties to obtain mining titles constrain women’s decent work outcomes. To support decent work in small-scale mining, the World Bank (2020) report on the sector also recommends interventions that target health and improve wellbeing. Provision of quality education would also importantly provide the base to catalyse innovation for higher added value products from minerals.

R&D, digitalisation and green funding

Strategic investment in research and development (R&D) is crucial. Africa will struggle to achieve the goals of a green industrialisation agenda without significant investment in training and R&D. If mineral-rich countries are to derive additional value from their resources, they need to invest in training not only geologists and mining engineers, but also process, chemical and electrical engineers. Value addition relies on innovation in technology, but also on knowledge. UNESCO’s (2021) science report External link, opens in new window. notes that Africa’s countries spend on average 0.6 per cent of GDP on R&D – far below the world average of 1.8 per cent and the OECD average of 2.4 per cent. Digital technologies are transforming the world, and the digital divide between Africa and the rest of the world is wide. According to a recent report from Brookings

External link, opens in new window. notes that Africa’s countries spend on average 0.6 per cent of GDP on R&D – far below the world average of 1.8 per cent and the OECD average of 2.4 per cent. Digital technologies are transforming the world, and the digital divide between Africa and the rest of the world is wide. According to a recent report from Brookings External link, opens in new window. (2023), the digital gap between Africa and richer countries is particularly severe in areas such as access to internet and digital skills. Within African countries, there are also digital gaps according to income, gender and rural-urban disparities. Africa’s digital development would thus need to include policy interventions to enhance digital skills across the population and would need to take account of the local context. For mineral-rich countries, strategic investment in digital technologies and R&D targeting the mineral sector is important. Machine learning, for example, can accelerate learning in battery mineral chemistry

External link, opens in new window. (2023), the digital gap between Africa and richer countries is particularly severe in areas such as access to internet and digital skills. Within African countries, there are also digital gaps according to income, gender and rural-urban disparities. Africa’s digital development would thus need to include policy interventions to enhance digital skills across the population and would need to take account of the local context. For mineral-rich countries, strategic investment in digital technologies and R&D targeting the mineral sector is important. Machine learning, for example, can accelerate learning in battery mineral chemistry External link, opens in new window. and efficiency in mineral refining

External link, opens in new window. and efficiency in mineral refining External link, opens in new window.. Collaboration between African universities and institutions of higher learning globally could lead to the joint development of technologies that reduce costs and enhance the use of Africa’s natural resources. Greater interdisciplinary collaboration is also important in understanding the broader societal challenges of more intensive mining exploration.

External link, opens in new window.. Collaboration between African universities and institutions of higher learning globally could lead to the joint development of technologies that reduce costs and enhance the use of Africa’s natural resources. Greater interdisciplinary collaboration is also important in understanding the broader societal challenges of more intensive mining exploration.

Investment in renewable energy is expensive and requires long-term funding. Several debt-distressed mineral-rich African countries face difficulties in attracting capital for long-term investment, which makes additional external finance important. International financial institutions have announced various programmes to increase the mobilisation of green finance. For example, the African Development Bank launched the African Green Bank initiative at the COP27 meeting in Egypt in November 2022. The EU has launched its Global Gateway to support investment in renewable energy and climate adaptation in Africa and elsewhere. This could potentially catalyse the synergies between Africa’s green industrialisation plans and the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism External link, opens in new window., and thus facilitate access to the EU market for Africa’s industrial products processed with green energy. However, there are also concerns that the mechanism could have a negative impact on African exports

External link, opens in new window., and thus facilitate access to the EU market for Africa’s industrial products processed with green energy. However, there are also concerns that the mechanism could have a negative impact on African exports External link, opens in new window..

External link, opens in new window..

Policy recommendations

- Expand expertise in international trade, mineral and environmental law to leverage better deals with multinational corporations and to address international trade conflicts that may arise from geoeconomic fragmentation and the strategic significance of green minerals.

- Widen and deepen regional cooperation. The AfCFTA provides opportunities for the deeper and more sustainable integration of African economies. Value addition can be accelerated by enlarging markets, improve availability of technologies and integrate labour markets. Digital technologies provide important opportunities to identify producers and consumers across the continent as well as a payment system that simplify intra-African transactions. Allowing goods and services to flow freely across African borders is a prerequisite to stimulate value addition in the mineral sector.

- Develop a clear policy and regulatory framework for the creation and management of mineral wealth. Collaboration between governments, civil society organisations and mining producers is essential to ensure that resource-extraction activities adhere to environmental and social standards, respect human rights and contribute to sustainable development.

- Engage in global dialogue to re-shape regulatory frameworks and standards for the mineral sector and its products, for example electric batteries, to ensure that they align with Africa’s mining vision and country development agendas.

- Integrate the small-scale mining sector into plans for green industrialisation, recognising its significance for decent employment and supporting the sector through training, access to finance, equipment, energy, logistics, and access to markets. Additionally, through public policies that build up human capital such as quality healthcare and education.

- Invest in greater collaboration between universities and other research institutes within Africa and the rest of the world to further the development of mining and related industrial technologies and to understand the broader societal challenges of more intensive mining. Together, promote programmes that not only address the gaps in digital literacy and skills, but foster innovation in the sector and ensure Africa’s broader participation in the green transition and digital economy.

- Engage with international financial institutions and initiatives, such as the African Green Bank and the EU’s Global Gateway, to secure long-term and affordable financing for renewable energy projects.

NAI Policy Notes is a series of research-based briefs on relevant topics, intended for strategists and decision makers in foreign policy, aid and development. It aims to inform and generate input to the public debate and to policymaking. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute. The quality of the series is assured by internal peer-reviewing processes.

About the authors

- Cristiano Lanzano is a social anthropologist with a background in political science and development studies. He is an expert on the extractive sector and mining.

- Jörgen Levin is a development economist specialised on inclusive growth, taxation and public spending.

- Patience Mususa is an environmental anthropologist whose research centres on mining and human settlement, green transition, urbanisation, and community welfare.

How to refer to this policy note:

Lanzano, Cristiano; Levin, Jörgen; Mususa, Patience (2024). Yesterday mineral supplier, tomorrow battery producer : How green industrialisation can push Africa's economies up the global value chains. (NAI Policy Notes, 2024:2). Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:nai:diva-2951 External link, opens in new window.

External link, opens in new window.

On a related note

Value unearthed: Africa's mineral resources strategy shift

African nations are working to boost the value of their mineral resources globally. But, hurdles like infrastructure gaps, tech limitations, and complex regulations stand in the way. Will Africa overcome these challenges?