Patriarchal politics, online violence and silenced voices

The decline of women in politics in Zimbabwe

Chitungwiza, Zimbabwe, 30 August 2023. A woman walking past a wall with a painted message calling for “Fresh Elections”, referring to the main opposition party's demand for fresh elections that meet regional standards. Photo: Zinyange Auntony, AFP.

In this year's elections in Zimbabwe, the number of women nominated and elected to national office decreased. This decline can be attributed to increased online harassment of women in politics, as well as financial obstacles and patriarchal attitudes. To reverse this trend, it is crucial for the government, political parties and civil society to address gender-based electoral violence effectively. Additionally, the government should genuinely implement gender quotas, focusing on empowering women in politics rather than using quota as a means to improve their international image, attract international donor funds and secure more women voters.

By Shingirai Mtero, Mandiedza Parichi and Diana Højlund Madsen

Zimbabwe held elections on 23 and 24 August 2023 to elect a new president, members of parliament and local government authorities. The main focus of the elections was the ‘battle of the titans’ between the incumbent, President Emmerson Mnangagwa, representing the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) party, and Nelson Chamisa, representing the main opposition party, Citizens Coalition for Change (CCC). Although the voting days were described as calm, preliminary reports by election observers from the African Union (AU) External link, opens in new window. and the Southern African Development Community (SADC)

External link, opens in new window. and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) External link, opens in new window. determined that the elections had not met the requirements of either Zimbabwe’s constitution or SADC’s principles and guidelines governing democratic elections.

External link, opens in new window. determined that the elections had not met the requirements of either Zimbabwe’s constitution or SADC’s principles and guidelines governing democratic elections.

The Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (ZEC) announced that Mnangagwa had won the presidential election, obtaining 52.6 percent External link, opens in new window. of the national vote. The CCC rejected

External link, opens in new window. of the national vote. The CCC rejected External link, opens in new window. this outcome and appealed to SADC

External link, opens in new window. this outcome and appealed to SADC External link, opens in new window. and the AU to intervene, asserting that a Zimbabwean court would not overturn the election results. These diplomatic appeals did not yield immediate results and Mnangagwa was sworn in as president of Zimbabwe on 4 September 2023. In its final report

External link, opens in new window. and the AU to intervene, asserting that a Zimbabwean court would not overturn the election results. These diplomatic appeals did not yield immediate results and Mnangagwa was sworn in as president of Zimbabwe on 4 September 2023. In its final report External link, opens in new window., SADC recommended that all grievances related to the outcome of the elections needed to be directed to the relevant domestic courts in Zimbabwe.

External link, opens in new window., SADC recommended that all grievances related to the outcome of the elections needed to be directed to the relevant domestic courts in Zimbabwe.

Commissioner Janet Ramatoulie Sallah-Njie, the AU’s Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Women in Africa, went to Zimbabwe to observe the elections. Sallah-Njie said she was encouraged External link, opens in new window. by Zimbabwean women’s enthusiasm to participate in the electoral process. But with the focus of the election on the fight between the two 'Big Men'

External link, opens in new window. by Zimbabwean women’s enthusiasm to participate in the electoral process. But with the focus of the election on the fight between the two 'Big Men' External link, opens in new window., concerns over gender and women’s representation were treated as peripheral.

External link, opens in new window., concerns over gender and women’s representation were treated as peripheral.

Sallah-Njie cautioned the government over reports of escalating political tension and attacks on voters and members of political parties, especially women, both online and offline. She warned that violent gendered prejudices drove these online attacks and could result in physical violence against women. The rise in online and offline harassment of women in politics has made women’s participation in elections less safe in Zimbabwe. Data from a 2023 Afrobarometer report External link, opens in new window. shows that 75 percent of Zimbabweans believe women should have the same chances as men to be elected for political office, but 58 percent acknowledge that once elected, women are at higher risk of criticism or harassment.

External link, opens in new window. shows that 75 percent of Zimbabweans believe women should have the same chances as men to be elected for political office, but 58 percent acknowledge that once elected, women are at higher risk of criticism or harassment.

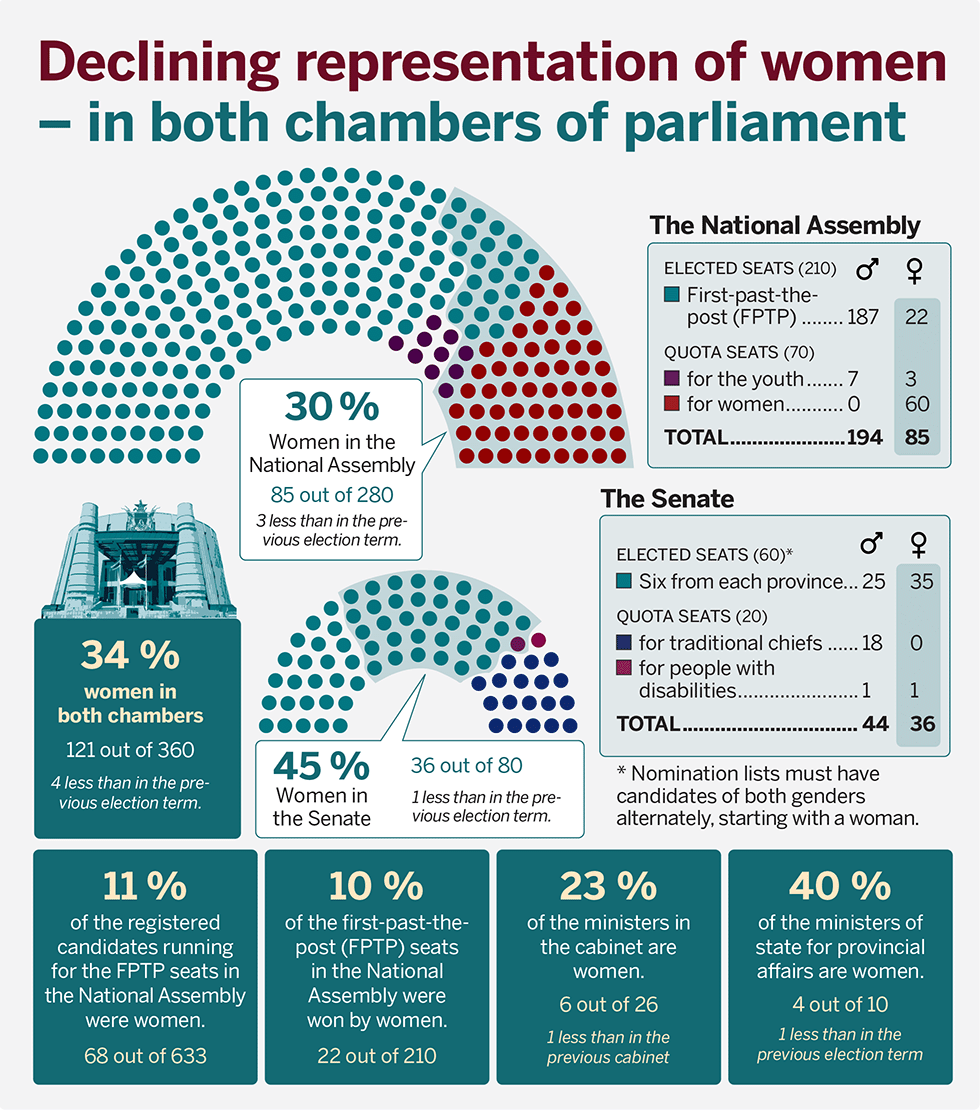

Source: Data collected through the ongoing research project Making Politics Safer – Gendered Violence and Electoral Temporalities in Africa. (At the time of publication, some female CCC parliamentary and local government representatives had been recalled from their positions. As such the figures displayed here may change).

Significant losses...

In 2023, the number of women nominated to contest Zimbabwe’s elections declined significantly. Candidate data External link, opens in new window. collected for the research project Making Politics Safer – Gendered Violence and Electoral Temporalities in Africa

External link, opens in new window. collected for the research project Making Politics Safer – Gendered Violence and Electoral Temporalities in Africa External link, opens in new window. shows that of 633 registered candidates running for 210 first-past-the-post (FPTP) parliamentary seats, only 68 (11 percent), were women. FPTP means that the candidate who gets the most votes in their constituency wins, even if it is less than half the votes. Of the 68 women candidates, ZANU-PF fielded 23 (34 percent), the CCC 20 (29 percent) and the remaining 25 were from minority parties (27 percent) or independent candidates (10 percent).

External link, opens in new window. shows that of 633 registered candidates running for 210 first-past-the-post (FPTP) parliamentary seats, only 68 (11 percent), were women. FPTP means that the candidate who gets the most votes in their constituency wins, even if it is less than half the votes. Of the 68 women candidates, ZANU-PF fielded 23 (34 percent), the CCC 20 (29 percent) and the remaining 25 were from minority parties (27 percent) or independent candidates (10 percent).

In the Senate, 36 women (45 percent) were elected. In the National Assembly, 60 women were elected through the quota, 22 were elected through FPTP voting and three were elected through the youth quota, bringing the total to 85 women representatives (30 percent). Overall, women’s representation in the Zimbabwean Parliament stands at 34 percent, which just exceeds SADC’s minimum requirement or a critical mass of 30 percent, but falls short of gender parity. Only six ministers, six deputy ministers and five permanent secretaries (who are not elected but appointed by the president), out of a total of 67 appointees, were women.

Lack of financial resources also played a role in the exclusion of women candidates, especially in the competitive FPTP elections. The candidature fees were raised by 20 times since last election (2018) – for presidential candidates from USD 1,000 to 20,000 and for parliamentarian candidates from USD 50 to 1,000. Exorbitant fees exclude women from political participation, especially in the competitive FPTP elections – and, in particular, women from minority parties and independent candidates. For this reason, many women candidates failed to raise enough capital to successfully campaign. Linda Masarira External link, opens in new window. wanted to run for president but did not contest the presidency because she could not raise the fee required for a presidential nomination. Both the AU and SADC linked increased nomination costs to the decline in women’s political participation. The findings of an AU and Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa joint election observation mission emphasised that these fees undermined “Zimbabwe’s constitutional aspiration and international/regional commitment towards gender equality.”

External link, opens in new window. wanted to run for president but did not contest the presidency because she could not raise the fee required for a presidential nomination. Both the AU and SADC linked increased nomination costs to the decline in women’s political participation. The findings of an AU and Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa joint election observation mission emphasised that these fees undermined “Zimbabwe’s constitutional aspiration and international/regional commitment towards gender equality.”

ZEC’s arbitrary application of financial policies also exclude women. ZEC initially disqualified the only woman in the presidential race, Elisabeth Valerio External link, opens in new window., for paying late in local currency: ZEC had allegedly advised her to pay in US dollars to avoid disqualification. In Zimbabwe, both the US dollar and the Zimbabwe dollar are recognised as legal tender. However, the US dollar is preferred and in many instances government agencies, such as ZEC, discourage or refuse payments in Zimbabwe dollars. This is not done officially, but is arbitrarily applied depending on the agency or government department. Valerio took ZEC to court, successfully challenged the decision to disqualify her and had her nomination reinstated.

External link, opens in new window., for paying late in local currency: ZEC had allegedly advised her to pay in US dollars to avoid disqualification. In Zimbabwe, both the US dollar and the Zimbabwe dollar are recognised as legal tender. However, the US dollar is preferred and in many instances government agencies, such as ZEC, discourage or refuse payments in Zimbabwe dollars. This is not done officially, but is arbitrarily applied depending on the agency or government department. Valerio took ZEC to court, successfully challenged the decision to disqualify her and had her nomination reinstated.

…and small gains

Amid the significant gender losses in the 2023 elections, there were small gender gains. The number of women representatives in local government increased due to the extension of the quota to local government level External link, opens in new window.. In Bulawayo Province, the smallest of Zimbabwe’s ten provinces in terms of population, the proportion of women councillors increased to 39 percent

External link, opens in new window.. In Bulawayo Province, the smallest of Zimbabwe’s ten provinces in terms of population, the proportion of women councillors increased to 39 percent External link. from 31 percent in 2018; in Harare Province, the largest province in terms of population, women’s representation increased to 36 percent

External link. from 31 percent in 2018; in Harare Province, the largest province in terms of population, women’s representation increased to 36 percent External link, opens in new window. from 12 percent

External link, opens in new window. from 12 percent External link, opens in new window.. The cities of Masvingo and Mutare elected their first female mayors, and the capital Harare elected its first female deputy mayor.

External link, opens in new window.. The cities of Masvingo and Mutare elected their first female mayors, and the capital Harare elected its first female deputy mayor.

Nonetheless, since the implementation of the national gender quota in 2013, with each election the number of women representatives in the National Assembly, Senate and Cabinet of Zimbabwe has declined. This slow regression indicates a bias within political parties against women candidates, driven by patriarchal beliefs Opens in new window. that portray women as being weak

Opens in new window. that portray women as being weak External link, opens in new window.. These prejudices are also evident in the way women in politics are harassed and threatened online.

External link, opens in new window.. These prejudices are also evident in the way women in politics are harassed and threatened online.

Escalating online violence

The democratic space for physical protest has diminished significantly in Zimbabwe since the highly contested elections in July 2018, when the army shot at protesters External link, opens in new window. in Harare, killing six people and injuring 35. The state-led clampdown on protests has pushed Zimbabweans to increasingly use social media as a platform for political engagement.

External link, opens in new window. in Harare, killing six people and injuring 35. The state-led clampdown on protests has pushed Zimbabweans to increasingly use social media as a platform for political engagement.

This is especially true for women. A 2020 report External link, opens in new window. by international non-governmental organisation Hivos looked at how women leaders use social media in Zimbabwe. The study showed that social media has become a critical tool for political agency, allowing women leaders to access a larger political base, campaign for support, share ideas with each other and voters, and engage in activism. But the Hivos study also revealed another side to the story. It showed that male dominance in Zimbabwe extends to social media, replicating the patriarchal attitudes that reinforce sexist attitudes towards women offline, and that online abuse against women is increasing.

External link, opens in new window. by international non-governmental organisation Hivos looked at how women leaders use social media in Zimbabwe. The study showed that social media has become a critical tool for political agency, allowing women leaders to access a larger political base, campaign for support, share ideas with each other and voters, and engage in activism. But the Hivos study also revealed another side to the story. It showed that male dominance in Zimbabwe extends to social media, replicating the patriarchal attitudes that reinforce sexist attitudes towards women offline, and that online abuse against women is increasing.

Janet Ramatoulie Sallah-Njie warned External link, opens in new window. that allegations of persistent online violence targeting women involved in Zimbabwean politics should not be ignored. She implored the government to “strengthen its efforts in combatting hate speech and harmful content, that fuel animosity and incite violence against women in politics.” Without such measures to safeguard women representatives, Sallah-Njie warned that women could eventually leave active politics.

External link, opens in new window. that allegations of persistent online violence targeting women involved in Zimbabwean politics should not be ignored. She implored the government to “strengthen its efforts in combatting hate speech and harmful content, that fuel animosity and incite violence against women in politics.” Without such measures to safeguard women representatives, Sallah-Njie warned that women could eventually leave active politics.

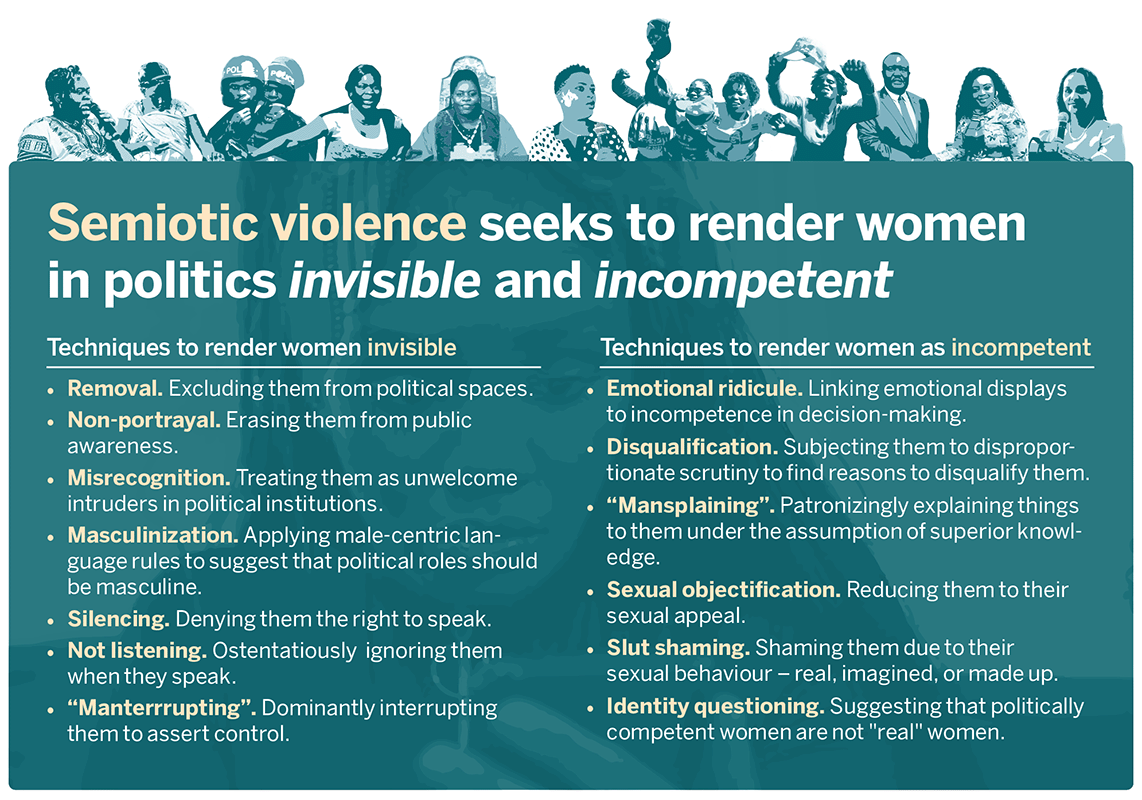

Gender scholar Mona Lena Krook describes these types of attacks as semiotic violence External link, opens in new window., in which semiotic resources – such as words, images and body language – are deployed to injure, discipline and subjugate women. Semiotic violence also shapes public perceptions of female politicians, and can lead to women being judged as incompetent or unfit for political office.

External link, opens in new window., in which semiotic resources – such as words, images and body language – are deployed to injure, discipline and subjugate women. Semiotic violence also shapes public perceptions of female politicians, and can lead to women being judged as incompetent or unfit for political office.

Modified version of a model introduced by gender scholar Mona Lena Krook in Violence against Women in Politics (2020).

Examples of online violence

This form of violence is prevalent in Zimbabwean online media. Women politicians are routinely attacked when they question male power. For example, Linda Masarira challenged journalist Hopewell Chin’ono over his position on xenophobia on social media platform ‘X’ (formerly Twitter). Chin’ono did not respond to Masarira’ s questions but instead tweeted her that she should ‘go and take a bath External link, opens in new window.’. Masarira is often attacked by online ‘trolls’ as she is dark skinned (an example of ‘colourism’). Chin’ono weaponised Masarira’ s appearance, ignoring the substantive question she had raised.

External link, opens in new window.’. Masarira is often attacked by online ‘trolls’ as she is dark skinned (an example of ‘colourism’). Chin’ono weaponised Masarira’ s appearance, ignoring the substantive question she had raised.

Young female leaders are also attacked over personal matters such as their marital status, age and sexual history. Fadzayi Mahere, is a member of parliament for the CCC and an accomplished constitutional lawyer. Although her professional accomplishments are well known, trolls have repeatedly attacked her for not having a husband and children. For example, X user @CdeBhanan’ana tweeted External link, opens in new window.: “rumour is saying Mahere has been involved in sex relationships for long, these [relationships] have been used as a Curriculum Vitae for acquiring high posts”. X user @Mananabula2 asked

External link, opens in new window.: “rumour is saying Mahere has been involved in sex relationships for long, these [relationships] have been used as a Curriculum Vitae for acquiring high posts”. X user @Mananabula2 asked External link, opens in new window.: “How can one run a constituency when she can’t have a husband...constituency problems are way bigger than those of a marriage”.

External link, opens in new window.: “How can one run a constituency when she can’t have a husband...constituency problems are way bigger than those of a marriage”.

In both instances Mahere’s marital status is used against her. In the first example, it is implied that she has used sex to ascend the CCC leadership rather than her qualifications. In the second, her competence as a leader is questioned, not because she lacks professional experience, but because she has failed to secure a husband. More recently, above a picture of Tatenda Mavetera, the Minister for Information and Communication Technology, X user @jahman_adamski External link, opens in new window., a political commentator with more than 58,000 followers, posted the comment, “ladies and gentlemen, I present to you the Honourable Dr Ambitious Smallhouse (Mistress).” The implication was that Mavetera had been appointed as a minister because she was a ‘smallhouse’ or mistress to a high-ranking ZANU-PF official.

External link, opens in new window., a political commentator with more than 58,000 followers, posted the comment, “ladies and gentlemen, I present to you the Honourable Dr Ambitious Smallhouse (Mistress).” The implication was that Mavetera had been appointed as a minister because she was a ‘smallhouse’ or mistress to a high-ranking ZANU-PF official.

Using an intersectional approach to analyse the typology of violence women are subjected to is important. Gender, age, marital status, sexuality/assumed sexual behaviour and political affiliation intersect to create a particular type of female politician that is highly susceptible to semiotic violence. This violence is driven by patriarchy and hegemonic masculinity in politics. If women are unmarried, single parents or widowed External link, opens in new window., they are represented as immoral and rebellious

External link, opens in new window., they are represented as immoral and rebellious External link, opens in new window. and therefore unfit to be politicians. Fuelled by these prejudices, the persistent attacks make political participation less safe for women and deter them from running for public office.

External link, opens in new window. and therefore unfit to be politicians. Fuelled by these prejudices, the persistent attacks make political participation less safe for women and deter them from running for public office.

Online media has also been used to invalidate claims of physical political violence against women. In 2020, three opposition leaders, Joana Mamombe, Cecilia Chimbiri and Netsai Marova External link, opens in new window., were allegedly abducted and sexually assaulted for participating in an anti-government protest. Police dismissed their claims and jailed the women for allegedly faking their own abductions. Zimbabwean media published stories

External link, opens in new window., were allegedly abducted and sexually assaulted for participating in an anti-government protest. Police dismissed their claims and jailed the women for allegedly faking their own abductions. Zimbabwean media published stories External link, opens in new window. that depicted the women as liars

External link, opens in new window. that depicted the women as liars External link, opens in new window., promiscuous

External link, opens in new window., promiscuous External link, opens in new window. or mentally unstable

External link, opens in new window. or mentally unstable External link, opens in new window.. The women’s online persecution and subsequent criminal prosecution indicate that Zimbabwean institutions are unwilling to address gendered political violence.

External link, opens in new window.. The women’s online persecution and subsequent criminal prosecution indicate that Zimbabwean institutions are unwilling to address gendered political violence.

While physical violence was not recorded on the election days in August 2023, there were reports of gendered electoral violence in by-elections and primaries in March that year. Between 2018 and July 2022, Zimbabwean civil society organisation Women's Academy for Leadership and Political Excellence (WALPE) recorded 37 cases of gendered political violence against women, including an attack on Thokozile Dube External link, opens in new window., a CCC ward candidate from Matabeleland. WALPE Director Sitabile Dewa asserted

External link, opens in new window., a CCC ward candidate from Matabeleland. WALPE Director Sitabile Dewa asserted External link, opens in new window. that, “the reoccurrence of violence during elections has continuous negative ripple effects to the participation of women in electoral processes.”

External link, opens in new window. that, “the reoccurrence of violence during elections has continuous negative ripple effects to the participation of women in electoral processes.”

The misappropriation of the gender quota

Zimbabwe first implemented the gender quota External link, opens in new window. through the new constitution

External link, opens in new window. through the new constitution External link, opens in new window. in 2013, reserving seats for women through proportional representation. Between 2008 and 2013, in the National Assembly and Senate, respectively, women’s representation rose from 14 percent to 32 percent, and from 33 to 48 percent; However, women’s representation then declined in the 2018 elections, to 31 percent and 46 percent, respectively. Of these women, only 12 percent were elected through FPTP voting, and only 13 percent of local government councillors were women. Responding to the extremely low level of women’s representation in local government, a constitutional amendment

External link, opens in new window. in 2013, reserving seats for women through proportional representation. Between 2008 and 2013, in the National Assembly and Senate, respectively, women’s representation rose from 14 percent to 32 percent, and from 33 to 48 percent; However, women’s representation then declined in the 2018 elections, to 31 percent and 46 percent, respectively. Of these women, only 12 percent were elected through FPTP voting, and only 13 percent of local government councillors were women. Responding to the extremely low level of women’s representation in local government, a constitutional amendment External link, opens in new window. was introduced in 2021 to extend the 30 percent gender quota.

External link, opens in new window. was introduced in 2021 to extend the 30 percent gender quota.

In theory, the purpose of the gender quota is to increase women’s representation and ultimately to achieve gender parity – 50/50 female-to-male representation. It is worrying that even under the quota, the number of women nominated and elected continues to decline. This contradiction is a result of the misappropriation of the quota. Instead of using it to increase women’s representation, political parties are segregating women to the quota. By nominating so few women for constituency seats, political parties are reducing the overall number of women who can be elected into office – in effect, using the quota to sequester women’s participation in representative politics.

Often, countries adopt a gender quota after making what political scientist Melody Valdini calls an ‘inclusion calculation External link, opens in new window.’, that weighs up the costs and benefits to the regime of including women. For Zimbabwe, using the quota to feminise governance structures could be beneficial as it would improve the nation’s international standing and assist in securing international aid. Women’s inclusion could be instrumental in securing political parties’ success by winning more female voters. However, women representatives elected through the quota are often subjected to elite patriarchal bargaining

External link, opens in new window.’, that weighs up the costs and benefits to the regime of including women. For Zimbabwe, using the quota to feminise governance structures could be beneficial as it would improve the nation’s international standing and assist in securing international aid. Women’s inclusion could be instrumental in securing political parties’ success by winning more female voters. However, women representatives elected through the quota are often subjected to elite patriarchal bargaining External link, opens in new window. and less inclined to push ‘women’s issues’ as their loyalties are primarily to their political parties rather than to women at large.

External link, opens in new window. and less inclined to push ‘women’s issues’ as their loyalties are primarily to their political parties rather than to women at large.

Zimbabwe is a signatory to the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance External link, opens in new window., the Maputo Protocol

External link, opens in new window., the Maputo Protocol External link, opens in new window. and the SADC Protocol on Gender and Development

External link, opens in new window. and the SADC Protocol on Gender and Development External link, opens in new window.. Article 29(3) of the African Charter emphasises that states parties should “take all possible measures to encourage the full and active participation of women in the electoral process and ensure gender parity in representation at all levels, including legislatures.” However, as the 2023 elections have shown, Zimbabwe is moving further away from the regional guidelines it subscribes to.

External link, opens in new window.. Article 29(3) of the African Charter emphasises that states parties should “take all possible measures to encourage the full and active participation of women in the electoral process and ensure gender parity in representation at all levels, including legislatures.” However, as the 2023 elections have shown, Zimbabwe is moving further away from the regional guidelines it subscribes to.

Policy recommendations

- Online harassment of women in politics should be punishable by law. Zimbabwe’s Domestic Violence Act

External link, opens in new window. and Cyber and Data Protection Act

External link, opens in new window. and Cyber and Data Protection Act External link, opens in new window. should be operationalised to assign punitive criminal charges against individuals or organisations that use online platforms to threaten, harass and ridicule women representatives or women who aspire to participate in elections.

External link, opens in new window. should be operationalised to assign punitive criminal charges against individuals or organisations that use online platforms to threaten, harass and ridicule women representatives or women who aspire to participate in elections. - Online gendered electoral violence should be adequately addressed at national level. Key institutions such as the Zimbabwe Gender Commission, Zimbabwe Republic Police, ZEC and women’s organisations should collaborate to create a framework for a national council that responds to incidents of online and offline gendered electoral violence. Part IV of the Domestic Violence Act

External link, opens in new window. could be used as a model for this council.

External link, opens in new window. could be used as a model for this council. - Financial barriers to women’s participation in elections should be addressed. ZEC should reduce nomination fees to align with fees set across the region. A subsidy should be introduced for nomination costs for women and other marginalised groups.

- The Government of Zimbabwe and Zimbabwean political parties must meet their obligations to regional protocols on gender equality and parity. The gender quota should be used, in earnest, to increase women’s representation, and democratic plurality in the country. Civil society organisations and other stakeholders should use their influence to compel political parties to nominate more women outside the quota to achieve gender parity.

Further reading

The NAI policy notes series is based on academic research. For further reading on this topic, we recommend the following titles:

- Bhatasara, Sandra & Chiweshe, Manase (2021). Women in Zimbabwean Politics Post-November 2017.

External link, opens in new window. Journal of Asian and African Studies.

External link, opens in new window. Journal of Asian and African Studies. - Kambarani, Maureen (2006). Femininity, Sexuality and Culture: Patriarchy and Female Subordination in Zimbabwe.

External link, opens in new window. Africa Regional Sexuality Resource Centre.

External link, opens in new window. Africa Regional Sexuality Resource Centre. - Krook, Mona Lena (2020). Semiotic Violence

External link, opens in new window.; in Violence against Women in Politics. Oxford University Press.

External link, opens in new window.; in Violence against Women in Politics. Oxford University Press. - Mutsvairo, Bruce (2020). Disenchanting or Demoralizing: Zimbabwean Women Share their Social Media Experience.

External link, opens in new window. Hivos.

External link, opens in new window. Hivos. - Madsen, Diana Højlund (Ed.) (2020). Gendered institutions and women’s political representation in Africa

External link, opens in new window.. Africa Now. Bloomsbury and the Nordic Africa Institute.

External link, opens in new window.. Africa Now. Bloomsbury and the Nordic Africa Institute. - Ncube, Gibson (2020). Eternal mothers, whores or witches: the oddities of being a woman in politics in Zimbabwe

External link, opens in new window.. Agenda : Empowering women for gender equity, volume 34, Isuue 4, pages 25-33.

External link, opens in new window.. Agenda : Empowering women for gender equity, volume 34, Isuue 4, pages 25-33. - Valdini, Melody E (2019). The Inclusion Calculation: Why Men Appropriate Women's Representation

External link, opens in new window. (Oxford Academic, New York).

External link, opens in new window. (Oxford Academic, New York).

NAI Policy Notes are a series of research-based briefs on relevant topics, intended for strategists and decision makers in foreign policy, aid and development. They aim to inform and generate input to the public debate and to policymaking. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute. The quality of the series is assured by internal peer-review processes and plagiarism-detection software.

About the authors

- Shingirai Mtero is a postdoctoral researcher at the Nordic Africa Institute (NAI), where she is currently working with a research project on gendered electoral violence.

- Mandiedza Parichi is a lecturer at the Great Zimbabwe University. Her research interests are media and political representation and gender-based violence.

- Diana Højlund Madsen is a senior researcher at NAI. She leads a research project on gendered electoral violence in Ghana, Kenya and Zimbabwe.

How to refer to this policy note:

Mtero, Shingirai; Parichi, Mandiedza; Højlund Madsen, Diana (2023). Patriarchal politics, online violence and silenced voices: The decline of women in politics in Zimbabwe. (NAI Policy Notes, 2023:4). Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:nai:diva-2910 External link, opens in new window.

External link, opens in new window.

This policy brief is an outcome of the research project Making Politics Safer: Gendered Violence and Electoral Temporalities in Africa, funded by the Swedish Research Council, project-id 2022-03742_VR.