Preserving heritage, nurturing progress, raising social equity

Policy advice on how indigenous peoples can advance sustainable agriculture in Kenya

_red_web%20resolution.jpg)

Baringo, Kenya, May 2023. Jane Chepkwony, Jeremiah Kiprotich and Kibet Kipsang are climate activists belonging to two of Kenya's indigenous peoples – the forest-dwelling Ogieks and the agro-pastoralist Endorois. Photo: CEMIRIDE/IRRI.

Recognising and including the knowledge and leadership of indigenous peoples in building resilient food systems is crucial for equitable transformation. Kenyan decision makers must empower indigenous peoples to engage in local climate adaptation and agricultural sector planning, and at the same time protect those peoples’ rights.

By Eleanor Fisher, Nyang’ori Ohenjo, Mary Ng’endo and Jon Hellin

Social equity is at the core of climate-resilient agriculture. The 2015 Paris Agreement, a legally binding international treaty on climate change, enshrines equity and the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities, and respective capacities in the light of different national circumstances. To ensure fair and just societal transformation, it is fundamental that social equity underpins climate adaptation measures. As research on transformative adaptation External link, opens in new window. suggests, addressing climate justice means tackling the root causes of complex inequalities and making political choices about the (re)distribution of benefits.

External link, opens in new window. suggests, addressing climate justice means tackling the root causes of complex inequalities and making political choices about the (re)distribution of benefits.

To sustain the lives and livelihoods of indigenous peoples in Kenya, attention to social equity implies a whole-of-society approach that builds transformative pathways for sustainable agriculture, shared prosperity and decent work for all. This is vital for indigenous peoples, who hold a unique position as collective rights holders recognised in various policy frameworks by the UN, the African Union, and the state of Kenya.

Vulnerability to climate change

Standing on a hill overlooking Lake Bogoria in Kenya’s Rift Valley, a local leader points to pastureland that once provided good grazing for livestock and to fields where crops were cultivated. He describes how the pastures have dried out, and how, despite fertile soils, food crops no longer grow because of lack of rain. When it does rain, the rain is either light and scattered, or causes flooding because so many trees have been cut down to make charcoal. Charcoal burning is a coping strategy in dire times, a source of money for food and other necessities.

The leader points to nearby beehives saying even the bees have left to look for nectar and water. In an adjacent village, people recount how in the 1970s they were displaced from Lake Bogoria External link, opens in new window. for wildlife conservation – but today this brings few benefits, while tick-borne diseases and bird flu make life even more difficult.

External link, opens in new window. for wildlife conservation – but today this brings few benefits, while tick-borne diseases and bird flu make life even more difficult.

For the people in these communities, drought and unpredictable weather patterns have created a harsh environment that the recent rains have not alleviated. They are Endorois agro-pastoralists, a semi-nomadic indigenous people who for centuries have lived by herding cattle and goats around Lake Bogoria. Land, and the cattle and goats that graze it, are the basis of the Endorois’ livelihoods, but also of people’s identity, social relations and memories.

Among the Endorois, being equitable means sharing. In principle, those in need should be supported and everyone should be treated fairly. Local leaders and politicians should not display bias and should work to ensure that everyone has access to services, such as water, roads, health care and education. Nonetheless, these are communities where many inequalities undermine this principle.

Years of colonisation brought new cultures and social orders, and forced the eviction of people from their lands. Today, inequalities compound vulnerability and make building resilience to climate change even harder for women and young people, people with disabilities and older people. Inequalities are reinforced when leaders do not share information or benefit some people at the expense of others. Women, in particular, experience lack of empowerment. They live in a male-dominated society and have limited possibilities for influencing village decisions at the lowest level of decision-making in their communities.

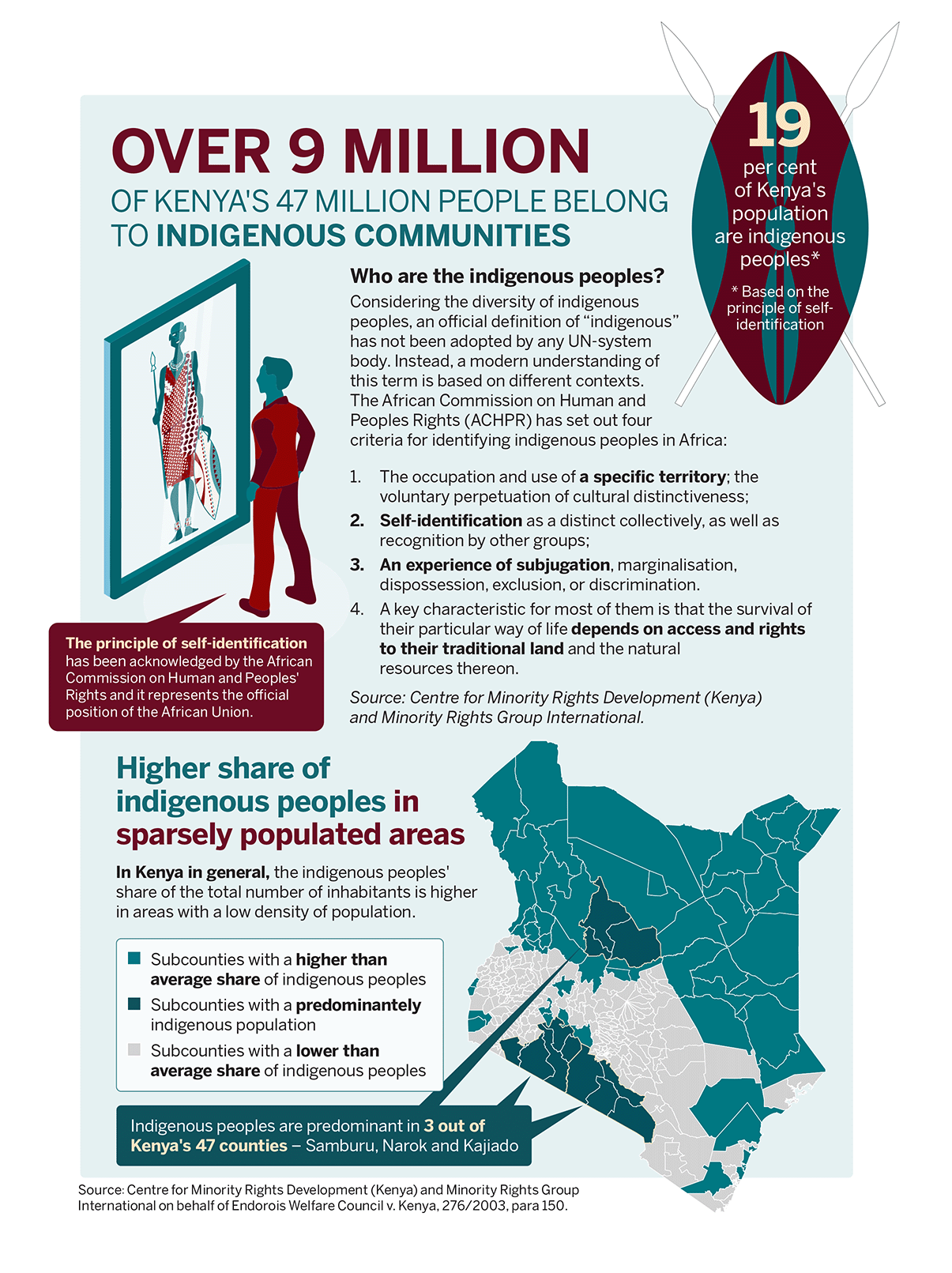

These communities in the Rift Valley are among the many diverse groups of indigenous peoples who live in different parts of Kenya. They are part of the almost 80 percent External link, opens in new window. of people in the country who depend on agriculture-based livelihoods for employment, income, nutrition and food security.

External link, opens in new window. of people in the country who depend on agriculture-based livelihoods for employment, income, nutrition and food security.

The majority of indigenous peoples in Kenya are pastoralists or agro-pastoralists, concentrated in the north and south. Geographically dispersed forest dwellers (hunter-gatherers) may practise agriculture, but they also rely on non-timber forest products. Fisher communities are dependent on inland bodies of water and the Indian Ocean. Pastoralism, hunting and gathering, and fishing all depend on land and other natural resources, which are tied to indigenous territories, ways of life, cultures, wellbeing and survival.

Many indigenous peoples lack access to land, natural resources or viable livelihood alternatives, including as a result of eviction External link, opens in new window.. Wider socioeconomic processes and poor access to services contribute to difficulties adapting to climate change. While there is potential to benefit from the ‘green transition’, projects to offset carbon

External link, opens in new window.. Wider socioeconomic processes and poor access to services contribute to difficulties adapting to climate change. While there is potential to benefit from the ‘green transition’, projects to offset carbon External link, opens in new window., intensify agriculture

External link, opens in new window., intensify agriculture External link, opens in new window. or generate renewable energy

External link, opens in new window. or generate renewable energy External link, opens in new window. all provoke controversy. Fears are raised over lack of respect for indigenous rights, appropriation of land, and minimal or non-existent benefit sharing.

External link, opens in new window. all provoke controversy. Fears are raised over lack of respect for indigenous rights, appropriation of land, and minimal or non-existent benefit sharing.

In Kenya, indigenous peoples are guaranteed land rights and protection from displacement, recognising the unique importance, and cultural and spiritual values that they attach to their lands, territories and natural resources. Unfortunately, in practice, laws and policies may be ignored, especially when the private sector negotiates business investment directly with the government. This carries the danger of maladaptation, increasing vulnerability to climate change by reproducing injustices and rights violations.

Climate effects on livelihoods and security

Agriculture is the mainstay of Kenya’s economy, comprising crops, livestock, fisheries and forestry. Many different institutions – government, private, parastatal and non-governmental – are involved in the sector. The central government is responsible for policy, while service provision is devolved to county governments, underlining the important role they play in food security. In its 2021 agricultural policy External link, opens in new window., the Government of Kenya cites utilisation of indigenous knowledge and resources as one of its guiding principles.

External link, opens in new window., the Government of Kenya cites utilisation of indigenous knowledge and resources as one of its guiding principles.

Moreover, in its Climate Smart Agriculture Strategy (2017–2026) External link, opens in new window., the government cites the potential of indigenous knowledge to help with climate adaptation, while highlighting the limited inventory and lack of a legal framework for indigenous knowledge. The strategy notes that the value of indigenous knowledge and skills will increase as the impacts of climate change become more pressing, and proposes integrating indigenous and scientific knowledge. However, it doesn’t specifically address what roles indigenous peoples themselves should play in climate-smart agriculture and how their rights should be safeguarded.

External link, opens in new window., the government cites the potential of indigenous knowledge to help with climate adaptation, while highlighting the limited inventory and lack of a legal framework for indigenous knowledge. The strategy notes that the value of indigenous knowledge and skills will increase as the impacts of climate change become more pressing, and proposes integrating indigenous and scientific knowledge. However, it doesn’t specifically address what roles indigenous peoples themselves should play in climate-smart agriculture and how their rights should be safeguarded.

Kenya is exposed to many natural hazards, the most common being floods and droughts. The World Bank External link, opens in new window. attributes over 70 percent of disasters in the country to extreme climatic events. The agricultural sector is highly vulnerable to such events, with climate risks posing a threat to agricultural livelihoods and challenging sustainability. Production losses are magnified by rising and novel infestations of insects, diseases and invasive species.

External link, opens in new window. attributes over 70 percent of disasters in the country to extreme climatic events. The agricultural sector is highly vulnerable to such events, with climate risks posing a threat to agricultural livelihoods and challenging sustainability. Production losses are magnified by rising and novel infestations of insects, diseases and invasive species.

The IPCC’s Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability report External link, opens in new window. identifies indigenous peoples in Africa as being profoundly vulnerable to the effects of climate variability and change. According to Kenya’s Second National Communication to the UNFCCC (2015)

External link, opens in new window. identifies indigenous peoples in Africa as being profoundly vulnerable to the effects of climate variability and change. According to Kenya’s Second National Communication to the UNFCCC (2015) External link, opens in new window., around 85 percent of Kenya’s land mass is a fragile arid and semi-arid ecosystem, where land use is largely by pastoralists. Droughts have a severe impact in arid zones. Conflict and other issues of insecurity in northern Kenya also contribute to vulnerability. Moreover, the expansion of crop farming into semi-arid areas is affecting the dynamics of pastoralism and contributing to conflict. Likewise, when combined with decreasing forest coverage and exclusions from forests that have served as a livelihood base for hunter gatherers, climate change is having negative impacts upon forest-based livelihoods. It is also affecting small-scale fisheries, including due to changes in fish populations and their distribution.

External link, opens in new window., around 85 percent of Kenya’s land mass is a fragile arid and semi-arid ecosystem, where land use is largely by pastoralists. Droughts have a severe impact in arid zones. Conflict and other issues of insecurity in northern Kenya also contribute to vulnerability. Moreover, the expansion of crop farming into semi-arid areas is affecting the dynamics of pastoralism and contributing to conflict. Likewise, when combined with decreasing forest coverage and exclusions from forests that have served as a livelihood base for hunter gatherers, climate change is having negative impacts upon forest-based livelihoods. It is also affecting small-scale fisheries, including due to changes in fish populations and their distribution.

The International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA) External link, opens in new window., a human rights organisation, underscores how vulnerable Kenya’s indigenous women are to climate risks, both because they belong to marginalised communities, and because they face internal social and cultural prejudices that deny them equal opportunities. Modern land ownership systems privilege men, and women’s essential roles in the agricultural and livestock-keeping workforce are systematically undervalued and underpaid.

External link, opens in new window., a human rights organisation, underscores how vulnerable Kenya’s indigenous women are to climate risks, both because they belong to marginalised communities, and because they face internal social and cultural prejudices that deny them equal opportunities. Modern land ownership systems privilege men, and women’s essential roles in the agricultural and livestock-keeping workforce are systematically undervalued and underpaid.

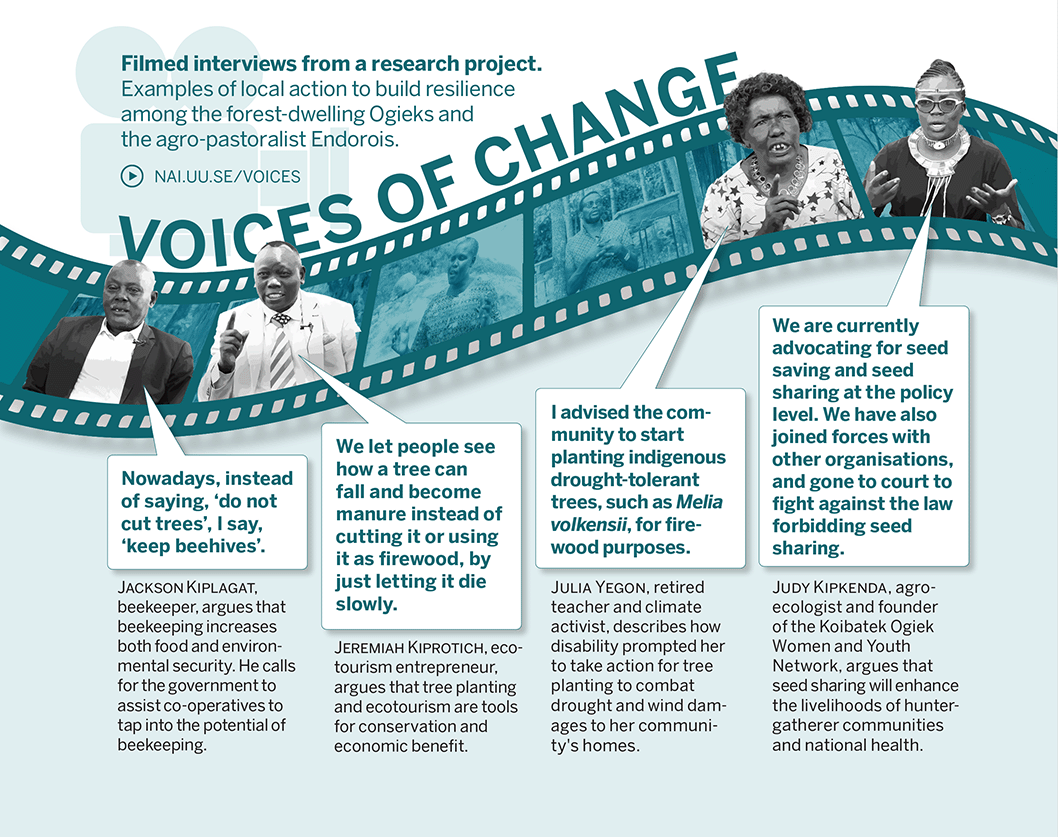

Local action to build resilience

While climate change poses profound challenges for indigenous peoples in Kenya, there are many positive examples of the value of indigenous leadership, knowledge and experience in building resilience. This includes how pastoralists know how to respond quickly External link, opens in new window. to changes in external conditions by moving their livestock.

External link, opens in new window. to changes in external conditions by moving their livestock.

Incorporating community voices External link, opens in new window. and experiences from diverse geographies helps foster food system sustainability

External link, opens in new window. and experiences from diverse geographies helps foster food system sustainability External link, opens in new window. in high-level decision-making forums. As Kenyan human rights organisation, the Centre for Minority Rights Development (CEMIRIDE)

External link, opens in new window. in high-level decision-making forums. As Kenyan human rights organisation, the Centre for Minority Rights Development (CEMIRIDE) External link, opens in new window. proposes, indigenous peoples can be advocates for change in ways that address their worldviews, rights and values within agricultural development.

External link, opens in new window. proposes, indigenous peoples can be advocates for change in ways that address their worldviews, rights and values within agricultural development.

Four types of equity

For local climate action to succeed in Kenya, it is important to integrate understanding based on the particular circumstances of indigenous peoples, recognising the significance of social equity. Ensuring representation, agency and a meaningful voice in decision-making is critical.

Internationally, this aligns with a four-year programme on agriculture and food security External link, opens in new window. that the UNFCCC started in 2022. It recognises that adaptation is a priority for vulnerable groups, including women, indigenous peoples and small-scale farmers, and emphasises the value of indigenous knowledge systems. In Kenya, an example of how this is being addressed is through how the World Bank and the governments of Sweden and Denmark, among others, have supported the Government of Kenya to develop the Financing Locally-Led Climate Action programme

External link, opens in new window. that the UNFCCC started in 2022. It recognises that adaptation is a priority for vulnerable groups, including women, indigenous peoples and small-scale farmers, and emphasises the value of indigenous knowledge systems. In Kenya, an example of how this is being addressed is through how the World Bank and the governments of Sweden and Denmark, among others, have supported the Government of Kenya to develop the Financing Locally-Led Climate Action programme External link, opens in new window..

External link, opens in new window..

Four types of social equity External link, opens in new window. are relevant to achieving the whole-of-society approach that needs to guide locally-led climate action:

External link, opens in new window. are relevant to achieving the whole-of-society approach that needs to guide locally-led climate action:

- Recognitional equity to embrace different identities, values and rights, rejecting cultural assimilation, and recognising how indigenous knowledge is integrated into people’s ways of life. Alongside valuing cultural diversity, and promoting women’s rights and gender equality, recognitional equity points to the need to reduce the vulnerability of minority groups within indigenous communities, including young people, older people, and people with disabilities.

- Representational equity to empower indigenous peoples to shape agricultural strategy by having a meaningful and effective role in decision-making that includes women and other vulnerable groups.

- Distributional equity to ensure indigenous peoples have equitable access to the benefits of climate-resilient agriculture; and, furthermore, that adaptation strategies do not expose vulnerable groups to greater risk or generate further unequal burdens.

- Intergenerational equity to enable indigenous peoples to secure stewardship of land and natural resources for future generations.

With attention to recognitional, representational, distributional and intergenerational equity comes the potential for building participatory parity to secure indigenous peoples’ full participation in society through locally led, climate-resilient, transformative pathways.

Policy recommendations

- National government should empower indigenous peoples, including women, young people and people with disabilities, to participate meaningfully in agricultural sector planning by enhancing mechanisms for diverse and inclusive participation in decision-making– for example, through the Climate Smart Agriculture Multi-Stakeholder Platform (CSA-MSP), chaired and hosted by the Climate Change Unit of the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries and Co-operatives.

- County governments should promote indigenous peoples’ roles in building climate-sensitive agriculture by strengthening their involvement in the design of locally led adaptation planning, and by promoting stakeholder platforms for county-level climate-resilient agriculture. The allocation of finances to support agricultural extension service delivery – for example, via the FLLoCA Program

External link, opens in new window. – can encourage the adoption of climate-resilient agriculture. Stimulating value chains and markets would further support indigenous peoples’ use of climate-resilient agricultural practices.

External link, opens in new window. – can encourage the adoption of climate-resilient agriculture. Stimulating value chains and markets would further support indigenous peoples’ use of climate-resilient agricultural practices. - Donor organisations can enable indigenous community-based organisations to shape and benefit from climate-smart agricultural programmes by investing in strengthening civil society – for example, by providing workshops on advocacy and skills development.

- Government planners and private sector investors must in practice embrace human rights safeguards for climate-sensitive agricultural investments that affect indigenous peoples. They include effective consultation in the design and implementation of the proposed investments based on the Free, Prior, and Informed Consent principle

External link, opens in new window., in line with Sessional Paper No. 03 of 2021 on National Action Plan on Business and Human Rights

External link, opens in new window., in line with Sessional Paper No. 03 of 2021 on National Action Plan on Business and Human Rights External link, opens in new window..

External link, opens in new window.. - National, county, and local authorities, and the international community, have to recognise that indigenous agricultural knowledge draws on people’s values, worldviews, and ways of life. Indigenous peoples must have sovereignty over their knowledge to craft solutions that build resilience and adaptation to the impact of climate change, while protecting their rights. An example is the Rights-based Innovative Traditional Knowledge Tool

External link, opens in new window. for co-production in climate monitoring and weather forecasting.

External link, opens in new window. for co-production in climate monitoring and weather forecasting. - All stakeholders, including the indigenous communities themselves, must address social equity in responses to the impacts of climate change on the agriculture sector; in particular, by recognising that indigenous women (including women with disabilities and young women) are especially vulnerable, given their limited access to resources and services. There is strong evidence that climate change affects women and men differently.

Further reading

The NAI policy notes series is based on academic research. For further reading on this topic, we recommend the following titles:

- CEMIRIDE. 2022. Towards a rights-based innovative traditional knowledge tool for systematic weather forecasting and decision support by indigenous and local communities.

External link, opens in new window. Policy Brief.

External link, opens in new window. Policy Brief. - Fisher, E. and Hellin, J. 2022. Building systemic resilience to climate variability and extremes (ClimBeR): social equity in climate-resilient agriculture.

External link, opens in new window. ClimBeR Briefing Note. CGIAR and Nordic Africa Institute.

External link, opens in new window. ClimBeR Briefing Note. CGIAR and Nordic Africa Institute. - Hellin, J., et al. 2022. Transformative adaptation and implications for transdisciplinary climate change research.

External link, opens in new window. Environmental Research : Climate 1 023001.

External link, opens in new window. Environmental Research : Climate 1 023001.

NAI Policy Notes are a series of research-based briefs on relevant topics, intended for strategists and decision makers in foreign policy, aid and development. They aim to inform and generate input to the public debate and to policymaking. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute. The quality of the series is assured by internal peer-review processes and plagiarism-detection software.

About the authors

- Eleanor Fisher is Head of Research at the Nordic Africa Institute and senior social science advisor to the CGIAR Initiative on Climate Resilience.

- Nyang’ori Ohenjo is Chief Executive Officer at CEMIRIDE, Kenya, a partner to the CGIAR initiative on Climate Resilience.

- Mary Ng’endo is gender and social equity implementation lead of the CGIAR Research Initiative on Climate Resilience.

- Jon Hellin is co-lead of the CGIAR Initiative on Climate Resilience with the International Rice Research Institute.

How to refer to this policy note:

Fisher, Eleanor; Ohenjo, Nyang’ori; Ng’endo, Mary; Hellin, Jon (2023). Preserving heritage, nurturing progress, raising social equity : Policy advice on how indigenous peoples can advance sustainable agriculture in Kenya. (NAI Policy Notes, 2023:3). Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:nai:diva-2900 External link, opens in new window.

External link, opens in new window.

This policy brief is based on a collaboration between the Nordic Africa Institute (NAI), the Centre for Minority Rights Development (CEMIRIDE) External link, opens in new window., and the CGIAR Research Initiative on Climate Resilience (ClimBeR)

External link, opens in new window., and the CGIAR Research Initiative on Climate Resilience (ClimBeR) External link, opens in new window.. The authors would like to thank all funders who supported this research through their contributions to the CGIAR Trust Fund.

External link, opens in new window.. The authors would like to thank all funders who supported this research through their contributions to the CGIAR Trust Fund.