Actions to prevent pregnant girls from school dropout

Lessons learnt from Covid-19 in Uganda

Mbale, Uganda, 21 June 2017. Pupils in a primary school classroom. Photo: Sven Hansen.

A recent study conducted in south-western Uganda identifies five main barriers to school-age mothers returning to school following pregnancy: negative self-perception, childcare burdens, community and family tensions, a tense school environment and ineffective policies. This policy note offers advice to policy makers at all levels and in all sectors on what they should do to tackle these barriers.

By Viola Nilah Nyakato, Elizabeth Kemigisha, Faith Mugabi, Milka Nyariro and Susan Kools

Female education has been at the forefront of global and national development agendas for decades. International treaties and policies, such as the 1994 Cairo International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD), put reproductive health, the empowerment of women and gender equality on the development agenda. UN Sustainable Development Goal number 5 (SDG 5) aims to achieve gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls. And target 5.3 is to eliminate all harmful practices, such as childhood, early and forced marriage, and female genital mutilation.

Despite these ambitions, the advancement of girls’ education continues to face challenges, such as sexual and gender-based violence associated with early unplanned teenage pregnancy and motherhood, forced marriage, and the high risk of HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted infections. Efforts to advance policies and programmes to address these issues face a range of cultural, religious and economic impediments. For example, in 2018 Uganda launched its National Sexuality Education Framework, which encountered resistance from cultural and religious leaders. Due to risk avoidance, it was never rolled out and was instead replaced by a programme that focused exclusively on sexual abstinence.

Covid-19 and reversals in girls’ education

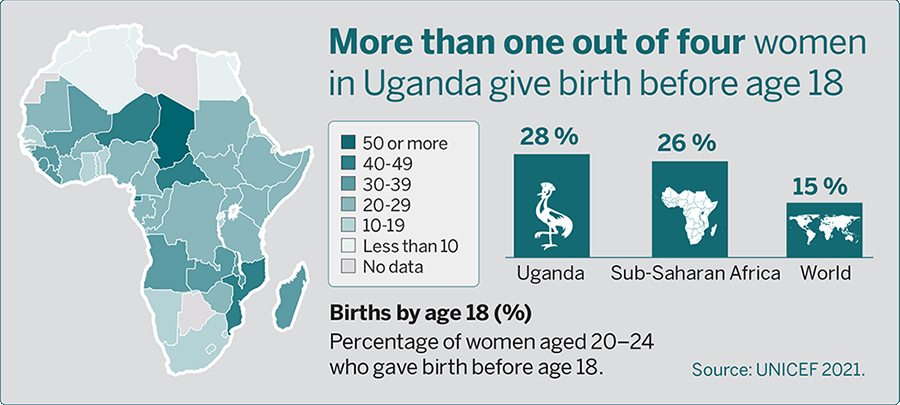

According to a recent report by Unicef (2021) External link, opens in new window., the percentage of women who give birth before the age of 18 is far higher in Sub-Saharan Africa than in most other regions, in average 26 per cent compared to a world average of 15 per cent. In Uganda, the rate is 28 per cent. Teenage pregnancy, adolescent childbearing and early marriage increase the risk that girls drop out of school. These are the leading drivers behind the widening gender gap in education. In most low-income countries, the Covid-19 pandemic has threatened education outcomes and progress on SDG 5. Girls’ education may have been the greatest disruption arising from increased adolescent pregnancy, sexual and gender-based violence, and child and forced marriage. Unesco estimates

External link, opens in new window., the percentage of women who give birth before the age of 18 is far higher in Sub-Saharan Africa than in most other regions, in average 26 per cent compared to a world average of 15 per cent. In Uganda, the rate is 28 per cent. Teenage pregnancy, adolescent childbearing and early marriage increase the risk that girls drop out of school. These are the leading drivers behind the widening gender gap in education. In most low-income countries, the Covid-19 pandemic has threatened education outcomes and progress on SDG 5. Girls’ education may have been the greatest disruption arising from increased adolescent pregnancy, sexual and gender-based violence, and child and forced marriage. Unesco estimates External link, opens in new window. that over 11 million girls may never return to school due to the Covid-19 disruption.

External link, opens in new window. that over 11 million girls may never return to school due to the Covid-19 disruption.

According to the 2020 Unesco Global Education Monitoring Report External link, opens in new window., the closure of schools at the peak of the Covid-19 pandemic disrupted formal learning and education in most countries, affecting more than 1.6 billion students in 194 countries, and exacerbating the situation in Sub-Saharan Africa. During the pandemic, over 15 million children were kept out of school for close to two years. In the course of the preparations to reopen schools, the Uganda National Planning Authority estimated that 30 per cent of all pre-Covid-19 school-going children may not return for various reasons, including teenage pregnancy and early marriage.

External link, opens in new window., the closure of schools at the peak of the Covid-19 pandemic disrupted formal learning and education in most countries, affecting more than 1.6 billion students in 194 countries, and exacerbating the situation in Sub-Saharan Africa. During the pandemic, over 15 million children were kept out of school for close to two years. In the course of the preparations to reopen schools, the Uganda National Planning Authority estimated that 30 per cent of all pre-Covid-19 school-going children may not return for various reasons, including teenage pregnancy and early marriage.

The rise of teen pregnancy and its costs

According to a recent report by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) External link, opens in new window. (2022), the number of teen pregnancies in Uganda increased by 6 per cent between 2019 and 2021 – from 358,000 to 379,000. A research report

External link, opens in new window. (2022), the number of teen pregnancies in Uganda increased by 6 per cent between 2019 and 2021 – from 358,000 to 379,000. A research report External link, opens in new window. commissioned by the Forum for African Women Educationalists (FAWE) analyses the impact of Covid-19, based on data collected in a survey of more than 3,000 randomly selected schoolgirls and young women aged 10–24 years, and comparative survey data from over 3,000 boys and young men, from randomly selected districts across Uganda. The study found that during the first six months of lockdown, from March to September 2020, the incidence of pregnancy increased by 366 per cent among girls aged 10–14. In the age groups 15–19 and 20–24, the increase was 25 per cent and 21 per cent, respectively, over the same period.

External link, opens in new window. commissioned by the Forum for African Women Educationalists (FAWE) analyses the impact of Covid-19, based on data collected in a survey of more than 3,000 randomly selected schoolgirls and young women aged 10–24 years, and comparative survey data from over 3,000 boys and young men, from randomly selected districts across Uganda. The study found that during the first six months of lockdown, from March to September 2020, the incidence of pregnancy increased by 366 per cent among girls aged 10–14. In the age groups 15–19 and 20–24, the increase was 25 per cent and 21 per cent, respectively, over the same period.

A recent report External link, opens in new window. by UNFPA and Uganda’s National Planning Authority on the economic and social burdens of teen pregnancy in Uganda estimated that USD 362 million were spent on the reproductive health care of teenage mothers in 2020. That is equivalent to 43 per cent of the Ministry of Health’s annual budget. Also, teenage pregnancy increases sexual gender-based violence victimization and failure to complete school. The report estimates that about 64 per cent of teen mothers will not complete primary education, and 60 per cent will end up in peasant agricultural work. Completing a secondary-school level of education improves employability by 73 per cent among girls and by 92 per cent among boys. Early school drop-out leads to a loss of economic opportunities.

External link, opens in new window. by UNFPA and Uganda’s National Planning Authority on the economic and social burdens of teen pregnancy in Uganda estimated that USD 362 million were spent on the reproductive health care of teenage mothers in 2020. That is equivalent to 43 per cent of the Ministry of Health’s annual budget. Also, teenage pregnancy increases sexual gender-based violence victimization and failure to complete school. The report estimates that about 64 per cent of teen mothers will not complete primary education, and 60 per cent will end up in peasant agricultural work. Completing a secondary-school level of education improves employability by 73 per cent among girls and by 92 per cent among boys. Early school drop-out leads to a loss of economic opportunities.

In addition, adolescent mothers are not physically mature and suffer increased maternal morbidity and mortality: teenage pregnancy contributes to 28 per cent of maternal deaths. Culturally, pregnancy out of wedlock is considered immoral and shaming for the girl, and frequently leads to forced marriage and/or abandonment.

A 2015 research report External link, opens in new window. by the New York-based international non-governmental organization (NGO) Population Council on the education sector’s response to early and unintended pregnancy in Sub-Saharan Africa shows that nearly all those girls who drop out of school due to pregnancy will not return: the figure ranges from 95 per cent in Zambia to 99 per cent in Tanzania. And many of those who do return face ridicule, blame and shame. Parenting teens are denied a second chance at education, because the school management fears that they will contaminate the ‘good’ girls who are in school; meanwhile they encounter negativity from family and community members, who blame them for bringing shame upon the family. The few who do return to school are likely to drop out because of the tense and hostile learning environments.

External link, opens in new window. by the New York-based international non-governmental organization (NGO) Population Council on the education sector’s response to early and unintended pregnancy in Sub-Saharan Africa shows that nearly all those girls who drop out of school due to pregnancy will not return: the figure ranges from 95 per cent in Zambia to 99 per cent in Tanzania. And many of those who do return face ridicule, blame and shame. Parenting teens are denied a second chance at education, because the school management fears that they will contaminate the ‘good’ girls who are in school; meanwhile they encounter negativity from family and community members, who blame them for bringing shame upon the family. The few who do return to school are likely to drop out because of the tense and hostile learning environments.

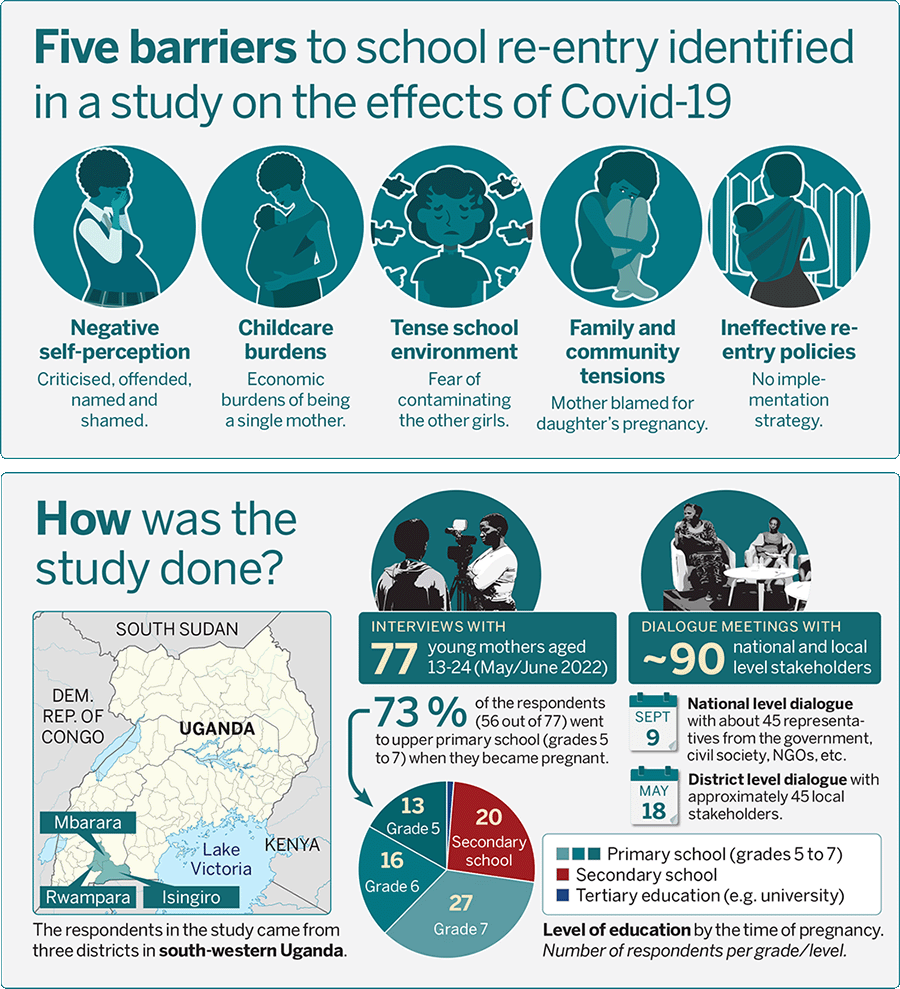

Study identifies barriers to a return to school

In May and June 2022, we conducted a qualitative assessment of educational aspirations and opportunities for after-pregnancy girls, with a focus on the effects of the Covid-19 lockdown. The study included focus group discussions (FGDs) and individual interviews with young mothers, their parents and young boys. It also builds on experiences drawn from two stakeholder dialogue meetings, one at national level and one at local level, with representatives from national ministries, government agencies, civil society organisations, international development partners, local governments, social service offices, teachers and religious leaders.

The study identifies five barriers to a return to school following pregnancy: negative self-perception, childcare burdens, family and community tensions, a tense school environment and ineffective school re-entry policies.

- Negative self perception. Those young mothers who are criticized, who endure offensive comments, and who are named and shamed for falling pregnant at a young age and outside marriage often suffer negative emotional and psychological effects. A quote from a parent about one of the young mothers in the study captures the dilemma:

My child got pregnant and after childbirth she went back to school, but it was not easy for her in class. Whenever she tried to concentrate, all in vain, she would instead cry and end up in deep thought. Eventually, she failed completely and decided to drop out again ... we did not know what to do. We were confused and later we decided to take her to a vocational training programme, where she is training in tailoring.

(FGD, parents/guardians, Rwekubo, May 2022)

- Childcare burdens. Most of the young mothers were single mothers, and often the burden of caring for the baby had been passed to their families. Here are a couple of quotes from young mothers in the study:

If my father can give me a second chance, I will be very willing to go back and study; but I also need to have a plan for who will take care of my baby back at home, so that when I am in school, I do not need to worry.

(Interview, pregnant adolescent, Isingiro, May 2022)

Most of our parents don’t want us to leave them with our babies. When they don’t have anything to feed them with they tell you to stay at home and look after your baby, you then also decide to stop schooling. If they agree to take care of the child, then you go back to school; and if they refuse, you just sit down at home and look after your baby.

(FGD, pregnant adolescents, Isingiro, May 2022)

- Family and community tensions. When a young girl gets pregnant, there is tension within her family caused by the lost dreams and aspirations of a good education and a better future for her. The pregnant girl’s mother is usually the one blamed for not bringing up a morally upstanding child.

As a mother, you have to allow and accept the situation, because when your husband finds out that his daughter is pregnant, he will put the blame on you and even abuse you, so you have to suffer but you have to withstand all of that so you have to take the burden and look after your daughter’s baby.

(FGD, parents/guardians, Mwizi, May, 2022)

Fathers sometimes are so harsh on their daughters if they become pregnant. Instead of giving them a second chance, the fathers will be chasing them away from their homes, making matters worse.

(FGD, parents/guardians, Rwekubo, May 2022)

- Tense school environment. Many of the pregnant schoolgirls are separated from the other students for fear that they will exert a negative influence on the other girls. The punishment of denying them schooling also serves as an example to deter other girls from what the school management labels irresponsible sexual behaviour.

When these girls get pregnant and get back to school, they feel out of place and uncomfortable, they get traumatized and stigmatized. Other students in school will be laughing at her, sometimes calling her a lot of names and other comments. So when such things like this happen to them, they feel they want to hide from the public for the rest of their lives.

(FGD, parents/guardians, Rwekubo, May 2022)

- Ineffective school re-entry policies. Most school return policies and guidelines are ineffective, while others – such as the Accelerated Education Programmes (AEPs), which are recognized by the Education Act 2008, or the 2021 Revised Guidelines for Prevention and Management of Pregnancy in School Settings, issued by the Ministry of Education and Sports – are not in use. Participants in the stakeholder dialogue meetings shared experiences of how the AEPs rolled out by NGOs had been effective among older students returning to school. A study by Save the Children

External link, opens in new window. on AEP for refugees also shows that the programmes greatly improve the transition from primary to secondary school. The same policies could be rolled out in other public and private schools for the general population.

External link, opens in new window. on AEP for refugees also shows that the programmes greatly improve the transition from primary to secondary school. The same policies could be rolled out in other public and private schools for the general population.

Uganda does not lack strategic programmes and policies that apply to this situation: the problem is some of these programmes remain dead letters. For example, Save the Children has used the Accelerated Education Programme to achieve school re-entry for refugee children living in camps across the country, and many children have returned to school under the programme; but for public schools it has remained a dead letter, although it dates as far back as 2008.

(Kampala, stakeholder dialogue meeting, May 2022)

Policy recommendations

The Ministry of Education and Sports should make schools safe for pregnant and parenting adolescents, by investing in:

- Counselling, childcare support, and sexual and reproductive health education

- Whole-school awareness campaigns on engagement, protection and connectedness, in order to reduce the risk of pupils dropping out of school and being discriminated against

- School communication campaigns to combat sexual and gender-based violence and gender inequality.

The government and its development cooperation partners should secure effective and comprehensive alternative learning environments, by:

- Assessing existing government, civil society and NGO initiatives on returning to school following pregnancy

- Securing funding for alternative learning environments that cater for the special needs of pregnant and parenting adolescents: for example, the need to escape from social shunning, to learn parenting skills and to combine schooling with income-generating activities.

Civil society and NGOs, in partnership with government departments and agencies, should remove the barriers to a return to school following pregnancy, by:

- Running community-level campaigns to eliminate stigma and shame, to discourage early marriage and to end sexual and gender-based violence

- Pursuing an integrated educational approach that includes improving family relations, promoting parenting skills, providing community-based and onsite childcare support, and engaging the fathers of the teenage mothers’ children

- Engaging cultural and religious leaders in advocacy and in finding solutions for inclusive education.

Development cooperation partners should promote and support government and non-government efforts towards a return to education following pregnancy, by:

- Strengthening girls’ and women’s organizations that work with sexual and reproductive health and rights

- Establishing and securing funding packages for national and local-level NGO advocacy initiatives for after-pregnancy school return

- Supporting capacity-building through cross-ministerial working groups and programmes on access to sexual and reproductive health education and services.

NAI Policy Notes are a series of research-based briefs on relevant topics, intended for strategists and decision makers in foreign policy, aid and development. They aim to inform and generate input to the public debate and to policymaking. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute. The quality of the series is assured by internal peer-review processes and plagiarism-detection software.

About the authors

- Viola Nilah Nyakato, Senior Researcher, Nordic Africa Institute and Senior Lecturer, Mbarara University of Science and Technology (MUST) in Uganda.

- Elizabeth Kemigisha, Lecturer, MUST.

- Faith Mugabi, social scientist and research intern, MUST.

- Milka Nyariro, Postdoc Fellow, Department of Family Medicine, McGill University, Canada.

- Susan Kools, Professor Emeritus at the Universities of Virginia and California San Francisco, USA, and Honorary Professor at MUST.

Further reading

The NAI policy notes series is based on academic research. For further reading on this topic, we recommend the following titles:

- Nyakato, V. N., Achen, C., Chambers, D., Kaziga, R., Ogunnaya, Z., Wright, M., & Kools, S. (2021). Very young adolescent perceptions of growing up in rural southwest Uganda: Influences on sexual development and behavior

External link, opens in new window.. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 25:2, 50-64.

External link, opens in new window.. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 25:2, 50-64. - Nyakato, V. N., Kemigisha, E., Tuhumwire, M., & Fisher, E. (2021). Covid reveals flaws in the protection of girls in Uganda: Recommendations on how to tackle sexual and gender based violence

External link, opens in new window.. NAI Policy Notes 2021:5. Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

External link, opens in new window.. NAI Policy Notes 2021:5. Nordiska Afrikainstitutet. - Nyariro, M. (2021). “We have heard you but we are not changing anything”: Policymakers as audience to a photovoice exhibition on challenges to school re-entry for young mothers in Kenya

External link, opens in new window.. Agenda, 35:1, 94-108.

External link, opens in new window.. Agenda, 35:1, 94-108.

How to refer to this policy note:

Nyakato, Viola Nilah; Kemigisha, Elizabeth; Mugabi, Faith; Nyariro, Milka and Kools, Susan (2022). Actions to prevent pregnant girls from school dropout : Lessons learnt from Covid-19 in Uganda. NAI Policy Notes, 2022:8. Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:nai:diva-2743 External link.

External link.