Gender gains overshadowed by constitutional violation

An analysis of the situation for women in politics after the 2022 Kenya elections

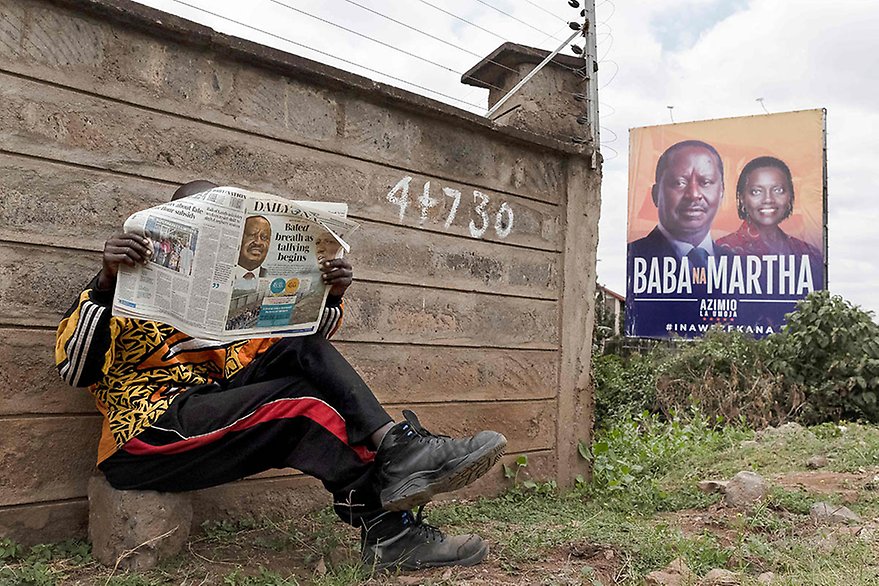

Nairobi, 10 August 2022. A man reads the Daily Nation newspaper while seated near a campaign billboard of Raila Odinga and his running mate Martha Karua, following Kenya's general election. Photo by Tony Karumba, AFP.

From a gender perspective, three main lessons can be learnt from the general election. First, gender issues are on the rise, a fact shown not least by the appointment of the first-ever women running mate for one of the two main presidential candidates. Second, although the ratios of women representatives at all levels are slowly but steadily increasing, the gender quota is just window dressing, which the parties blatantly ignore or work around by nominating women candidates to top-up lists. Third, violence against women in politics poses a serious threat to women’s political inclusion and citizenship.

By Shilla Sintoyia Memusi and Diana Højlund Madsen

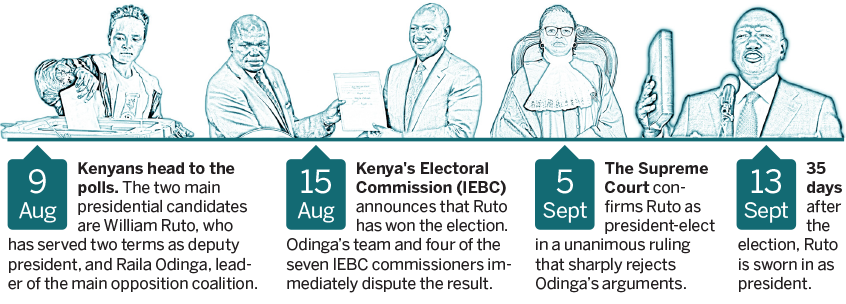

On 9 August, Kenyans headed to the polls to elect the country’s president. In addition to the executive, Kenyans also elected 290 members of parliament, 47 governors, 47 senators, 47 women representatives and 1,450 members of county assemblies in the elections. However, the executive race was the focus of attention. Both online and offline, the two presidential contenders William Ruto and Raila Odinga engaged in rhetoric to disparage the other, a tactic that succeeded because of – and was perpetuated by – the spread of misinformation External link, opens in new window..

External link, opens in new window..

Unlike in previous elections, the outgoing president, Uhuru Kenyatta, supported not his deputy, Ruto, but Odinga, whose party made up the opposition during Kenyatta’s term in office. Considering the proximity of both Ruto and Odinga to state power, there was tension over the parties’ reaction to the results. Mind games during the tallying period External link, opens in new window. did little to ease spreading anxiety, but most hoped for free and fair elections followed by a peaceful transition. This came to pass when the Supreme Court threw out a petition to block Ruto’s swearing-in

External link, opens in new window. did little to ease spreading anxiety, but most hoped for free and fair elections followed by a peaceful transition. This came to pass when the Supreme Court threw out a petition to block Ruto’s swearing-in External link, opens in new window..

External link, opens in new window..

The third election to be conducted under the 2010 Constitution, this year’s poll saw the formation of two main coalitions: Ruto’s Kenya Kwanza and Odinga’s Azimio la Umoja. Unsurprisingly, both candidates chose ethnic-Kikuyu running mates. Considering the history of ethnicised political violence in Kenya, this move served to defuse social tensions among the Kikuyu, the country’s largest ethnic group, who, for the first time in Kenya’s history, had no presidential candidate.

Odinga is an ethnic Luo, a community that has not had a successful presidential candidate, while Ruto is from the Kalenjin community, as was late president Daniel Arap Moi, who was in power for 24 years. In his book Multiethnic Democracy – The Logic of Elections and Policymaking in Kenya External link, opens in new window., Jeremy Horowitz observes that the party system in Kenya is weakly institutionalised and electoral alignments are shaped taking into consideration elite coalitions with ethnic affiliations. This also involves politics characterised by patronage/matronage and clientelism. This tactic is founded on the absence of parties based on a consistent political ideology. The instrumentalization of tribal identities and manipulation of ethnic grievances

External link, opens in new window., Jeremy Horowitz observes that the party system in Kenya is weakly institutionalised and electoral alignments are shaped taking into consideration elite coalitions with ethnic affiliations. This also involves politics characterised by patronage/matronage and clientelism. This tactic is founded on the absence of parties based on a consistent political ideology. The instrumentalization of tribal identities and manipulation of ethnic grievances External link, opens in new window. have therefore always informed political mobilisation. Consequently, the threat and often use of violence hang over every election cycle, especially since electoral violence in 2007-2008.

External link, opens in new window. have therefore always informed political mobilisation. Consequently, the threat and often use of violence hang over every election cycle, especially since electoral violence in 2007-2008.

It is therefore important to note the role of the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI) External link, opens in new window. in reducing ethnic tension between the Luo and Kikuyu communities. The BBI, a constitutional amendment bill of November 2020, emanated from the rapprochement between Kenyatta and Odinga after the 2017 post-election violence. According to its architects, the bill aimed to prevent the winner-takes-all system that experts say has been the main cause of electoral violence.

External link, opens in new window. in reducing ethnic tension between the Luo and Kikuyu communities. The BBI, a constitutional amendment bill of November 2020, emanated from the rapprochement between Kenyatta and Odinga after the 2017 post-election violence. According to its architects, the bill aimed to prevent the winner-takes-all system that experts say has been the main cause of electoral violence.

Kenyatta’s critics see the BBI process as an ill-disguised power grab by a president who has served two terms and is constitutionally barred from running for a third. However, a handshake in 2018 between Kenyatta and Odinga became the iconic symbol of the pair’s promise to heal the country’s divisions. Pre-election analysis External link, opens in new window. by UK-based NGO Saferworld points out that the landmark handshake contributed to a positive shift in relations between divided ethnic communities, especially in violence-prone hotspots such as Kibera in the capital Nairobi. Coupled with institutional reforms in the past decade, the formation of coalitions and strategic choice of deputies has contributed to reducing hostility between political parties and ethnic communities.

External link, opens in new window. by UK-based NGO Saferworld points out that the landmark handshake contributed to a positive shift in relations between divided ethnic communities, especially in violence-prone hotspots such as Kibera in the capital Nairobi. Coupled with institutional reforms in the past decade, the formation of coalitions and strategic choice of deputies has contributed to reducing hostility between political parties and ethnic communities.

Gender: a key issue for both coalitions

Odinga’s choice of Karua as deputy was an additional strategic move. Karua is known to be bold; she is a human rights defender, has served as a cabinet minister and vied for the presidency in 2013. Karua has been dubbed Kenya’s Iron Lady, a title she believes External link, opens in new window. reflects the misogyny and patriarchy in Kenyan society, where strength is perceived as male. Karua promised that her government would pay particular attention to socioeconomic rights, and her candidacy is a nod to the ongoing gender equality debate. While unveiling his deputy in May, Odinga stated:

External link, opens in new window. reflects the misogyny and patriarchy in Kenyan society, where strength is perceived as male. Karua promised that her government would pay particular attention to socioeconomic rights, and her candidacy is a nod to the ongoing gender equality debate. While unveiling his deputy in May, Odinga stated:

After 60 years of independence, we cannot excuse the male domination of the executive. For the first time in the history of our republic and on the seventh multi-party election, history is calling us to close the gender gap in our country. History is calling on us to reciprocate the struggles and fidelity of our women. History is calling on us to produce our first woman deputy president.

Karua’s candidacy was mostly positively received. Rahab Muiu, the chair of the largest women’s organisation in Kenya, Maendeleo ya Wanawake External link, opens in new window., declared that the nomination was well deserved and expressed confidence in Karua’s commitment to promoting a women friendly agenda. This points back to the gender equality debate with both coalitions highlighting the women’s agenda in their manifestos and efforts to win women’s votes.

External link, opens in new window., declared that the nomination was well deserved and expressed confidence in Karua’s commitment to promoting a women friendly agenda. This points back to the gender equality debate with both coalitions highlighting the women’s agenda in their manifestos and efforts to win women’s votes.

Ruto’s Kenya Kwanza coalition's manifesto External link, opens in new window., promised to provide financial and capacity-building support for women; to implement the two-thirds gender rule in elected and appointed positions in the public sector within 12 months; and to increase the number of gender desks and responsible personnel at police stations. However, Odinga’s Azimio la Umoja’s manifesto

External link, opens in new window., promised to provide financial and capacity-building support for women; to implement the two-thirds gender rule in elected and appointed positions in the public sector within 12 months; and to increase the number of gender desks and responsible personnel at police stations. However, Odinga’s Azimio la Umoja’s manifesto External link, opens in new window. promised to progressively aim for gender parity in appointments, and at the very least adhere to the two-thirds gender rule. It also pledged to enhance the professional capacity of young women in different areas and to establish incubation centres for businesses targeting women in rural areas, among other things. The women’s agenda clearly constituted a key focus area for both coalitions.

External link, opens in new window. promised to progressively aim for gender parity in appointments, and at the very least adhere to the two-thirds gender rule. It also pledged to enhance the professional capacity of young women in different areas and to establish incubation centres for businesses targeting women in rural areas, among other things. The women’s agenda clearly constituted a key focus area for both coalitions.

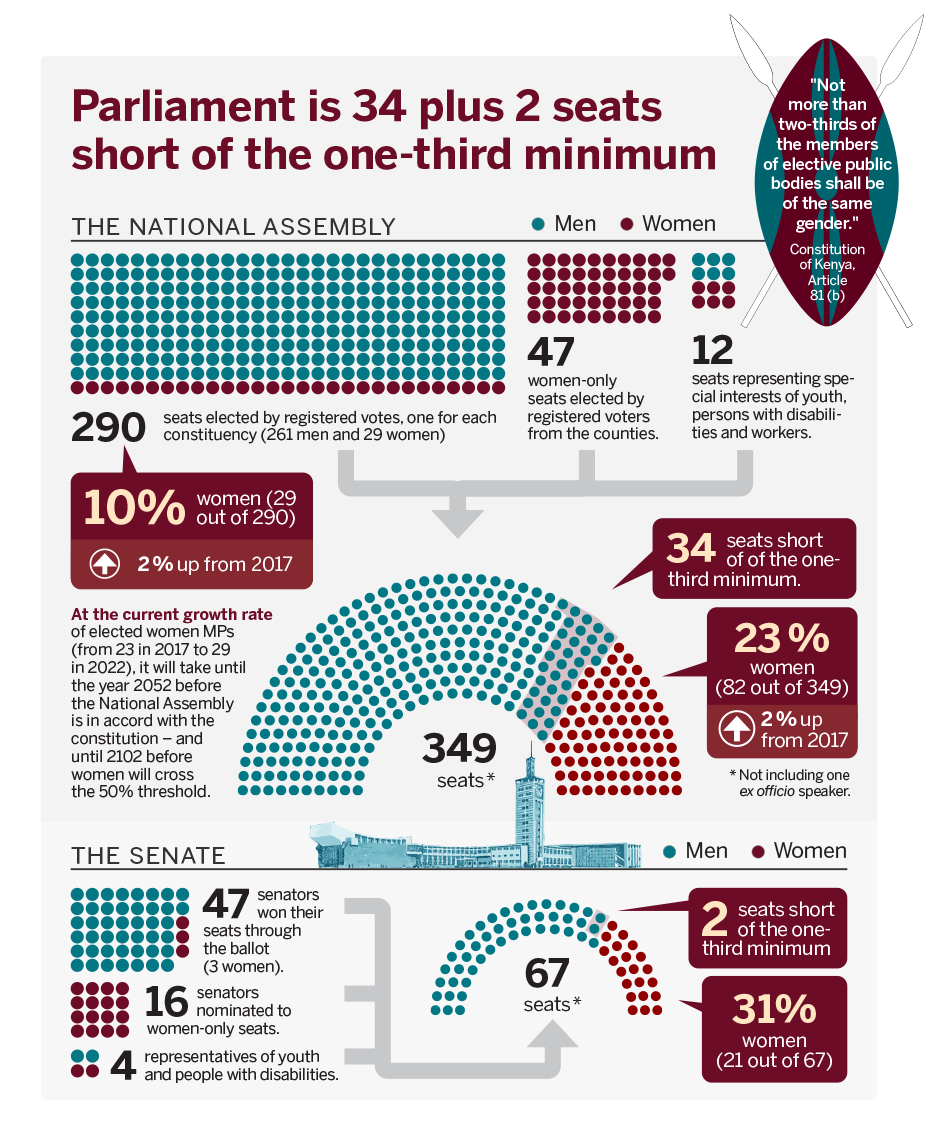

Gender quota: a choice, not an obligation

The gender quota was adopted in the last constitutional reform in 2010. Article 81(b) of the Constitution External link, opens in new window. states that “not more than two-thirds of the members of elective public bodies shall be of the same gender”. Article 177, which deals with the composition of the county assemblies, states that apart from the assembly members elected by the registered voters of the wards, the assembly should be expanded by ‘‘the number of special seat members necessary to ensure that no more than two-thirds of the membership of the assembly are of the same gender.’’

External link, opens in new window. states that “not more than two-thirds of the members of elective public bodies shall be of the same gender”. Article 177, which deals with the composition of the county assemblies, states that apart from the assembly members elected by the registered voters of the wards, the assembly should be expanded by ‘‘the number of special seat members necessary to ensure that no more than two-thirds of the membership of the assembly are of the same gender.’’

In practice, this is achieved through top-up lists that allow political parties to nominate women to meet the gender quota. But although they contribute to fulfilling gender quotas in the county assemblies, the top-up lists leave little room for substantive change. Unlike the elected members of the county assemblies, who owe their allegiance to their constituencies, women appointed as “special seat members” owe allegiance to their political parties. Their tokenistic representation does not allow them freedom to push for an agenda that may be against the interests of their male-dominated parties.

The practice of top-up lists is not explicit in this National Assembly, which throughout both periods after the introduction of the gender quota – the 11th Parliament (2013-2017) and the 12th Parliament (2017-2022) – operated in violation of the Constitution. The composition of the 12th Parliament would have required at least 117 women in the National Assembly and 23 in the Senate to fulfil the constitutional requirement. However, the two bodies had only 76 and 21 women, respectively.

Analysis of the quota in 2019 External link, opens in new window. by Kenyan NGO the Centre for Rights Education and Awareness concluded that there is an outright disregard by Parliament of court orders to implement the two-thirds principle, and related impunity. The main reason is lack of political will or a political culture that is not aligned with the intentions of the Constitution, making it difficult for Kenya to achieve gender parity. The quota is thus seen as a political choice rather than a constitutional obligation.

External link, opens in new window. by Kenyan NGO the Centre for Rights Education and Awareness concluded that there is an outright disregard by Parliament of court orders to implement the two-thirds principle, and related impunity. The main reason is lack of political will or a political culture that is not aligned with the intentions of the Constitution, making it difficult for Kenya to achieve gender parity. The quota is thus seen as a political choice rather than a constitutional obligation.

Violence and sexism

Researcher Maina wa Mũtonya, who has studied the patriarchical discourse that stands in the way of women in politics, concludes that cases of corruption against women politicians achieve greater prominence in the public debate and media coverage, not because of the women’s positions but because they are women. He also describes how women in politics at local level are labelled as ‘outsiders’ if their husbands belong to a different ethnic community, indicating that the benefits from the women winning would be directed elsewhere. Such attitudes played out in the 2022 primaries, leaving women terrified. Testimony from Violet Omwamba External link, opens in new window., one of the strongest candidates in Nyamira in Western Kenya, speaks for itself:

External link, opens in new window., one of the strongest candidates in Nyamira in Western Kenya, speaks for itself:

I was forced to step down because the community cannot be led by a woman. I was told if I wanted to vie, I should focus on the woman representative seat.

Such accounts are the background for different forms of violence against women External link, opens in new window., negatively affecting their active political engagement. Informal normative environments play a big role in shaping violence against women politicians in Kenya. In a BBC report

External link, opens in new window., negatively affecting their active political engagement. Informal normative environments play a big role in shaping violence against women politicians in Kenya. In a BBC report External link, opens in new window. on women candidates’ experiences during the campaign period, one woman who was running for a seat in the National Assembly told of how she had received online threats of gang rape.

External link, opens in new window. on women candidates’ experiences during the campaign period, one woman who was running for a seat in the National Assembly told of how she had received online threats of gang rape.

According to a recent Afrobarometer survey External link, opens in new window., 87% of Kenyans said that women should have the same chances as men of being elected; 77% say that female candidates and their families would gain standing in the community, but many (53%) also said they were likely to be criticised or harassed. This demonstrates that more needs to be done to make Kenya’s political space friendlier and more open to women.

External link, opens in new window., 87% of Kenyans said that women should have the same chances as men of being elected; 77% say that female candidates and their families would gain standing in the community, but many (53%) also said they were likely to be criticised or harassed. This demonstrates that more needs to be done to make Kenya’s political space friendlier and more open to women.

With the main focus being on the presidential debate, the media did not pay much attention to gender-based violence at the local level. However, gender-based violence, especially sexual harassment, has been on the rise. During the Covid-19 lockdown, cases of violence against women in Kenya increased, as they did across the world. The elections were held at a time when women were particularly vulnerable to violence. The safety of women during and outside of election cycles is therefore a matter of concern in the country.

Institutional barriers

In analysis of the potential drivers of violence External link, opens in new window. during the 2022 elections, International Crisis Group notes that critical institutions such as the IEBC were ill prepared. In addition to being underfunded, the post of chief executive officer of the commission was vacant for almost four years until March 2022, just five months before the election. On the other hand, public trust in the judiciary’s independence increased following the Supreme Court’s nullification of the results

External link, opens in new window. during the 2022 elections, International Crisis Group notes that critical institutions such as the IEBC were ill prepared. In addition to being underfunded, the post of chief executive officer of the commission was vacant for almost four years until March 2022, just five months before the election. On the other hand, public trust in the judiciary’s independence increased following the Supreme Court’s nullification of the results External link, opens in new window. of the 2017 presidential election. A 2021 study

External link, opens in new window. of the 2017 presidential election. A 2021 study External link, opens in new window. by the International Federation of Women Lawyers (FIDA Kenya) on legal and policy gaps that impede women’s political participation in Kenya found the judiciary to be the institution that was most committed to promoting women’s political participation. However, a High Court ruling

External link, opens in new window. by the International Federation of Women Lawyers (FIDA Kenya) on legal and policy gaps that impede women’s political participation in Kenya found the judiciary to be the institution that was most committed to promoting women’s political participation. However, a High Court ruling External link, opens in new window. to suspend the IEBC’s decision to blacklist political parties that did not meet the gender quota introduced doubts among campaigners for women’s political freedom over the judiciary’s commitment to enforcing Article 81(b).

External link, opens in new window. to suspend the IEBC’s decision to blacklist political parties that did not meet the gender quota introduced doubts among campaigners for women’s political freedom over the judiciary’s commitment to enforcing Article 81(b).

In this year’s elections, a lot of injustices against women candidates were perpetuated by and within political parties during the nomination process. For those who did not get direct nomination tickets, many lost to their male counterparts through in-party consensus building and voter bribery External link, opens in new window.. According to Beth Syengo, president of the Orange Democratic Movement’s Women’s League, besides using unorthodox means such as violence and propaganda to derail the campaigns of their female counterparts, men massively used bribery to get their party tickets.

External link, opens in new window.. According to Beth Syengo, president of the Orange Democratic Movement’s Women’s League, besides using unorthodox means such as violence and propaganda to derail the campaigns of their female counterparts, men massively used bribery to get their party tickets.

Mulle Musau, national coordinator of the Election Observation Group, a national platform comprising civil society organisations, with a mandate to strengthen democracy in Kenya, believes that these were boardroom decisions External link, opens in new window., and that money was a key factor. Opportunities, therefore, went to much better-resourced contenders, who were usually men. Overall, the constellation of institutional challenges, monetisation of electoral processes and normative environments that impede women’s political agency continue to make it difficult for women to compete fairly against men in Kenya’s political processes.

External link, opens in new window., and that money was a key factor. Opportunities, therefore, went to much better-resourced contenders, who were usually men. Overall, the constellation of institutional challenges, monetisation of electoral processes and normative environments that impede women’s political agency continue to make it difficult for women to compete fairly against men in Kenya’s political processes.

Beyond the small wins

The IEBC reported that of the candidates cleared to run for elective positions, only 1,962 were women, against 14,137 men. In the run-up to the elections, there were many efforts to support women’s political candidacy. For example, FIDA Kenya launched the Vote A Dada campaign during their Women Leadership Conference in August 2021, which focused on enhancing women’s participation in governance. Later, FIDA Kenya partnered with Womankind Worldwide on the Women Leadership Academy, a training programme to increase public discourse and promote women’s participation in the August 2022 polls. This was a forum for women legislators External link, opens in new window. to share their experiences with other women political aspirants, focusing on political party processes, campaign strategies, mental wellness and media training.

External link, opens in new window. to share their experiences with other women political aspirants, focusing on political party processes, campaign strategies, mental wellness and media training.

Despite all these efforts, in the end only 186 women were elected across 1,882 positions up for election. Ten counties did not elect any women External link, opens in new window., while Nakuru was the only county to meet the gender quota. Despite the small wins, the general outcome remains discouraging, and has prompted a rethink on efforts towards an increased representation of women. Ruto’s cabinet

External link, opens in new window., while Nakuru was the only county to meet the gender quota. Despite the small wins, the general outcome remains discouraging, and has prompted a rethink on efforts towards an increased representation of women. Ruto’s cabinet External link, opens in new window., which he unveiled a couple of weeks after he was sworn in as president, does not reflect his promise to commit to gender parity: only seven out of 22 ministers are women.

External link, opens in new window., which he unveiled a couple of weeks after he was sworn in as president, does not reflect his promise to commit to gender parity: only seven out of 22 ministers are women.

A recent Afrobarometer survey External link, opens in new window. shows that 56% of women in Kenya do not feel close to any political party, compared with 38% of men. This gap points towards a democratic trust deficit among women voters. This deficit may be reflected in the fact that this year’s general election had the lowest voter turnout in 15 years. However, the particular set-up with the presidential candidates and their historical links to the former president may also have played a role in this development.

External link, opens in new window. shows that 56% of women in Kenya do not feel close to any political party, compared with 38% of men. This gap points towards a democratic trust deficit among women voters. This deficit may be reflected in the fact that this year’s general election had the lowest voter turnout in 15 years. However, the particular set-up with the presidential candidates and their historical links to the former president may also have played a role in this development.

Policy recommendations

- Political parties need to respect the two-thirds gender principle in their lists of nominees. While the IEBC tried to sanction political parties that did not adhere to this rule, the decision was overturned in court. There is, therefore, a need for institutional cooperation in finally putting irreversible measures in place for non-compliance. The 2022 National Assembly should legislate a formula to achieve electoral gender parity in Kenya.

- Violence against women in politics should be adequately addressed through joint efforts by institutions such as the IEBC, the National Gender and Equality Commission and organisations working to advance women’s rights. The focus should be on countering gender norms that work against women in politics, promoting the benefits of gender-balanced representation in politics and providing tools for conflict mediation.

- Support for women political candidates exposed to violence needs to be in place in the form of clear systems for reporting and counselling. Political parties need to take a strong stance against gendered violence.

- Institutional barriers such as the competitive ‘first-past-the-post’ system

External link, opens in new window., and related patronage politics and monetisation of politics also work against women candidates. They should be addressed in parallel with implementation of the quota system. This is a long-term process, which should be initiated by the new government and preferably approved by all political parties.

External link, opens in new window., and related patronage politics and monetisation of politics also work against women candidates. They should be addressed in parallel with implementation of the quota system. This is a long-term process, which should be initiated by the new government and preferably approved by all political parties.

NAI Policy Notes are a series of research-based briefs on relevant topics, intended for strategists and decision makers in foreign policy, aid and development. They aim to inform and generate input to the public debate and to policymaking. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute. The quality of the series is assured by internal peer-review processes and plagiarism-detection software.

About the authors

- Shilla Sintoyia Memusi is a policy analyst with a PhD in development sociology from the University of Bayreuth, Germany. Her research expertise is on feminist institutionalism and women’s political representation.

- Diana Højlund Madsen is a senior researcher at the Nordic Africa Institute. Her research expertise is on gender and governance, women’s political representation, gender mainstreaming, and gender and conflict.

Further reading

The NAI policy notes series is based on academic research. For further reading on this topic, we recommend the following titles:

- Højlund Madsen, Diana (2021). Gendered Institutions and Women’s Political Representation in Africa

External link, opens in new window.: Africa Now Series, Bloomsbury / ZED Books and the Nordic Africa Institute.

External link, opens in new window.: Africa Now Series, Bloomsbury / ZED Books and the Nordic Africa Institute. - Højlund Madsen, Diana; Aning, Kwesi; Hallberg Adu, Kajsa (2020). A Step Forward but No Guarantee of Gender Friendly Policies

External link, opens in new window. – Female Candidates Spark Hope in the 2020 Ghanaian Elections; (NAI Policy Notes, 2020:7). Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

External link, opens in new window. – Female Candidates Spark Hope in the 2020 Ghanaian Elections; (NAI Policy Notes, 2020:7). Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet. - Memusi, Shilla S (2020). Gender Equality Legislation and Institutions at the Local Level in Kenya: Experiences of the Maasai

External link, opens in new window.; University of Bayreuth.

External link, opens in new window.; University of Bayreuth. - Memusi, Shilla S (2019). "What Can a Woman Say or Do?” Gender Norms and Public Participation among the Maasai in Kenya

External link, opens in new window..

External link, opens in new window..

How to refer to this policy note:

Memusi, Shilla S & Madsen, Diana H, 2022, Gender gains overshadowed by constitutional violation : An analysis of the situation for women in politics after the 2022 Kenya elections. NAI Policy Notes, 2022:7. Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:nai:diva-2714 External link.

External link.