Counter-terrorism has to be transborder and address root causes

Joint efforts key as jihadist violence spills over into Burkina Faso, Benin and Niger

Fishing in Pendjari in north western Benin, adjoining the Arli National Park in Burkina Faso. Photo: Jean Di Stasio.

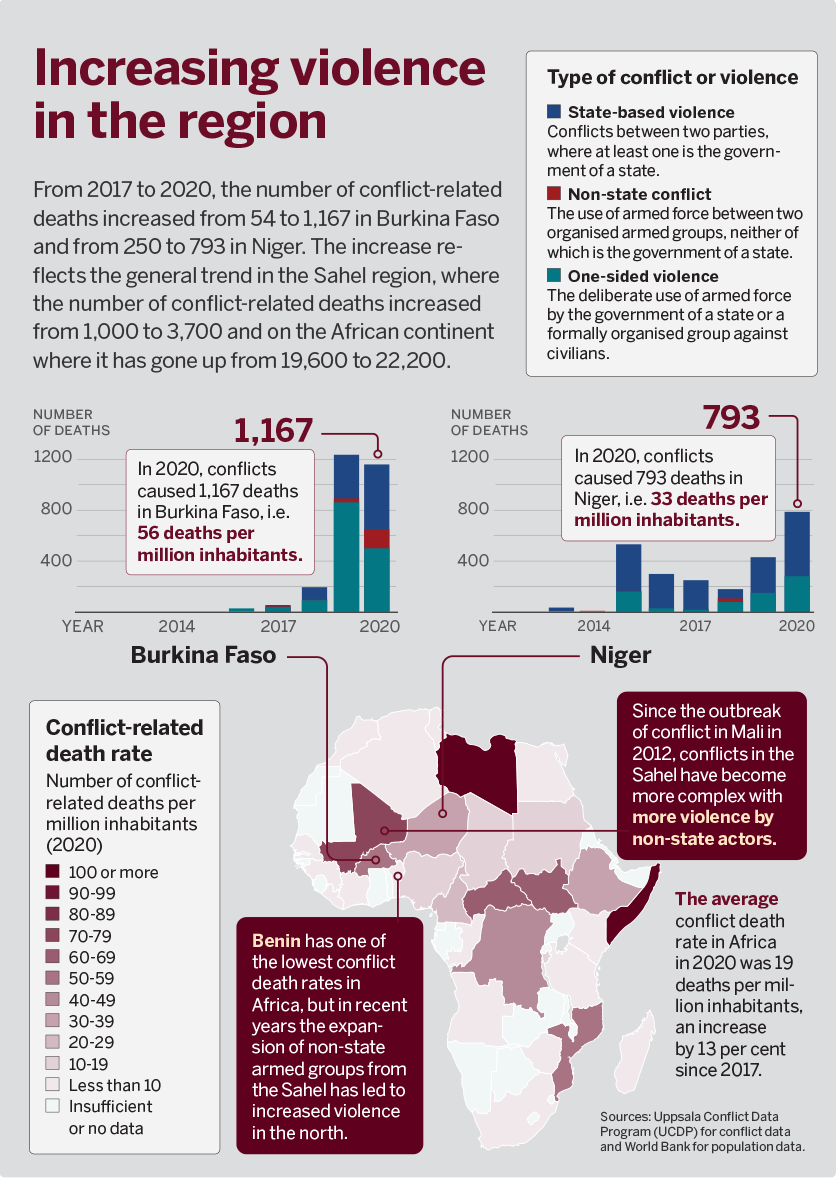

The spiral of violence in the Sahel is threatening to engulf the biosphere reserve in the cross-border territory shared by Burkina Faso, Benin and Niger. The rising violence is causing massive displacement and all three countries should respond jointly by mobilising and coordinating state armed forces to protect affected populations. But a joint military response is not enough. The three states should also collaborate to address the root causes of the insecurity: the land and pastoralism crisis; inconsistency in the distribution of forest resources; and a poorly integrated approach to managing the biosphere reserve.

By Papa Sow, senior researcher, the Nordic Africa Institute

Western media outlets External link, opens in new window. have attributed the violence that has flared in the ‘three borders’ area to armed jihadist groups affiliated to Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State. Having expanded their sphere of operations to the ‘point triple’ area, some of these armed groups have seized control of the management of fishing, poaching and hunting resources – transforming them into an eldorado

External link, opens in new window. have attributed the violence that has flared in the ‘three borders’ area to armed jihadist groups affiliated to Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State. Having expanded their sphere of operations to the ‘point triple’ area, some of these armed groups have seized control of the management of fishing, poaching and hunting resources – transforming them into an eldorado External link, opens in new window. and demanding the payment of tributes (zakat) – as well as the traffic in wood and various other goods. Given the steady rise in attacks, the challenge that arises is one of how to pacify the sprawling ‘point triple’ area while at the same time redefining the territorial governance of W Park.

External link, opens in new window. and demanding the payment of tributes (zakat) – as well as the traffic in wood and various other goods. Given the steady rise in attacks, the challenge that arises is one of how to pacify the sprawling ‘point triple’ area while at the same time redefining the territorial governance of W Park.

The presence of armed groups is not the only cause of political and social instability in W Park. Other issues also add to insecurity and vulnerability of different groups in the area: lack of consultation with local populations on security matters; the land and pastoralism crisis; inconsistency in the distribution of forest resources; and a poorly integrated approach to managing the biosphere reserve.

Spillovers from Mali

The proliferation of armed groups in the ‘three borders’ area, and by extension the ‘point triple’ area, can be linked to the decade-long conflict that started in Mali and has spilled over into neighbouring countries to the south and the west. The stagnation of peace agreements between the Malian state and the various armed factions involved in the conflict, the lack of success the foreign (primarily French) military presence has had in helping take control of corridors used for transhumance (cattle and pastures) and arms trafficking, coupled with the sheer, ungovernable size of Mali, has led to a perilous security situation. This in turn has spilled over into neighbouring countries.

Non-state armed Islamist groups operating in the ‘three borders’ area shared by Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger have headed southwards and are now active in the ‘point triple’ area shared by Benin, Burkina Faso and Niger. Moreover, the conflict has led to the stigmatisation of Fulani populations not only in Mali but in northern Benin and Burkina Faso. As a result, members of certain ethnic communities have been radicalised and gone on to join the armed groups.

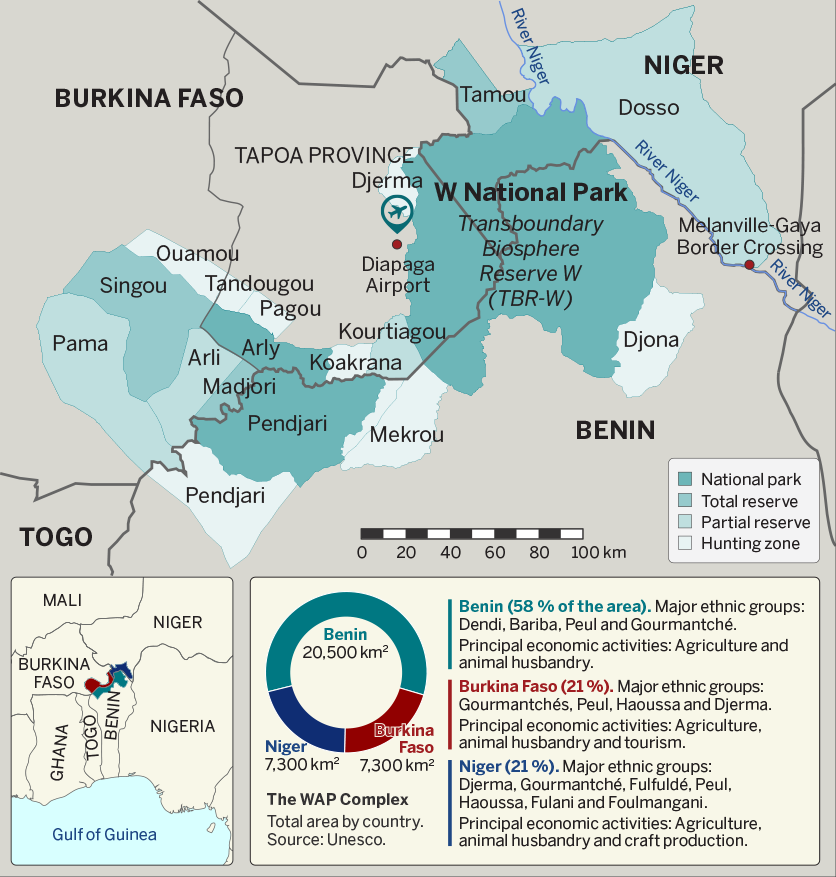

The W Transboundary Biosphere Reserve (TBR-W). An expanse of national parks, reserves and hunting zones that traverses Benin, Burkina Faso and Niger. The total area of the extended region, also known at the Point Triple Area or the WAP Complex, covers 35,000 square kilometres.

Deteriorating security in Burkina Faso

In Burkina Faso, a climate of terror has reigned in Tapoa – a province in the east of the country, located between Benin and Niger – since 2019, where non-state armed groups began invading forests and parks previously popular with foreign tourists. In these thick forests, the armed groups have not only taken control of resources but, in some locations, the extraction of gold. Moreover, the groups have attempted to capitalise on the local population’s frustrations and feeling of neglect towards the Burkinabe state (and by extension of the border states of Benin and Niger) by developing a parallel political economy in the spaces under their control.

The armed groups often distribute land and authorise the exploitation of local resources (hunting, fishing) to populations who consider themselves abandoned by the central authorities. One consequence of this is that some local gold miners have closely allied themselves with armed groups. The control of gold washing sites allows the armed groups to accumulate cash and create corridors for the trafficking of various goods (gold, cigarettes, drugs, armaments), which are often sent to ‘improvised clandestine ports’ in neighbouring coastal countries (Benin, Ghana, Togo). While some researchers, for example Lanzano et al (2021) External link, opens in new window., who have studied small scale mining in Burkina Faso, argue that “there is no automatic or 'natural' link between violence, insecurity and artisanal gold mining”, others such as Brottem (2022)

External link, opens in new window., who have studied small scale mining in Burkina Faso, argue that “there is no automatic or 'natural' link between violence, insecurity and artisanal gold mining”, others such as Brottem (2022) External link, opens in new window. and de Bruijne (2021)

External link, opens in new window. and de Bruijne (2021) External link, opens in new window., who have studied the growing threat of violent extremism in Coastal West Africa and Northern Benin, conclude that the management of natural resources is a driver of violence.

External link, opens in new window., who have studied the growing threat of violent extremism in Coastal West Africa and Northern Benin, conclude that the management of natural resources is a driver of violence.

In response to the violence, local populations in Burkina Faso have been mobilising ‘self-defence militias’ consisting of youth and people from civil society. Although the Burkinabe army general staff announced sweeps in the east of the country to carry out road clearance and excavations, the self-defence militias have demanded a larger mobilisation of the army and coordinated operations across the country. The conflict has also spread to Benin and Niger.

Increased violence in Benin and Niger

In northern Benin, the expansion strategy of non-state armed groups active in Mali, Niger and neighbouring Burkina Faso has led to increasing incidences of violence. In February 2020, for example, a Beninese policeman was killed in an attack on a post in W Park, while in May of the previous year, two French nationals, whose local guide has been found dead, were held for ransom following an excursion in Pendjari National Park, near the border with Burkina Faso.

The armed groups, which have arrived in northern Benin from Niger and Burkina Faso, have succeeded in creating and mastering routes in forest parks, allowing them to move around quickly and avoid capture. Moreover, they have begun using their forest cover to make regular incursions, attacking local populations and representatives of the state, which in turn has provoked the mobilisation of national armed forces and the displacement of populations.

Rising violence has also been seen in Niger, with an October 2021 attack on a police station in Tillabéry region, within the ‘three borders’ area, leading to three people being killed and seven wounded. The attack took place just as Niger president Mohamed Bazoum was engaged in an official visit to Burkina Faso to discuss security issues.

Meanwhile, civilian populations living close to the near 630 kilometre border between Niger and Burkina Faso have suffered abuses at the hands of the Al-Qaeda-affiliated Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims (GSIM), causing the displacement of entire families and exposing nearly 600,000 people to food insecurity.

W Park under threat

W Park is Africa’s first Transboundary Biosphere Reserve, recognised by Unesco External link, opens in new window.. According to a case study

External link, opens in new window.. According to a case study External link, opens in new window. by international law researcher Michelot and Burkinabé government official Ouedraogo, W Park has faced multiple pressures (wood cutting, hunting, poaching, fishing, harvesting of medicinal plants, illegal mining) leading to a level of exploitation that threatens the potential of the unique ecosystems contained within the reserve.

External link, opens in new window. by international law researcher Michelot and Burkinabé government official Ouedraogo, W Park has faced multiple pressures (wood cutting, hunting, poaching, fishing, harvesting of medicinal plants, illegal mining) leading to a level of exploitation that threatens the potential of the unique ecosystems contained within the reserve.

With the support of external partners, the three states have together put in place a management framework aimed at utilising the reserve’s natural resources for the purposes of local, national and regional development. To achieve this, a regional process for coordinating national policies has been adopted, with the participation of local populations in the common management of resources a focal point. Such processes have enabled a reduction in anthropogenic pressures, minimising and calming conflicts arising from exploitation practices and land tenure systems around the point of convergence between the three borders.

More recently, however, the future of the reserve – its conservation, as well as the sustainability of development activities aimed at local populations – has come under serious threat due to incursions by armed groups. These groups have ‘colonised’ this natural geographical area, and continue to live inside the park, committing abuses against populations who have largely been left to fend for themselves.

It would be overly simplistic, however, to assume that the armed groups are the sole cause of the current situation. Rather, it can also be seen as due to bankrupt political management, including negligence in maintaining the gains (forest protection management, socio-economic outcomes of the W Park, existing regulatory and institutional tools, etc) made since the 2000 Tapoa Declaration, whereby the three states agreed to put in place the legislative and institutional tools necessary to facilitate collaborative management of the region.

Since 2018, W Park has become a major corridor of banditry, providing sanctuary for all kinds of trafficking. Moreover, activities such as gold panning, hunting and fishing have fallen into the hands of the armed groups. Forest eco-guards – poorly equipped, poorly trained and long considered predatory by local populations – have found themselves the target of these armed groups. As such, numerous guards have either been killed by the armed groups or else recruited into their ranks. Meanwhile, many of the forest guards who remain loyal to the three states refrain from visiting the forest areas of W Park due to a lack of ammunition.

This confused situation has reinforced mistrust between the different communities and between forest guards and communities. It has also helped foster insurgencies that are then exploited by the armed groups, which have developed organised criminal networks that feed on cross-border banditry. In order to shield themselves from cattle theft and/or the crisis of pastoralism (land pressure on grazing areas and transhumance corridors), or simply to seek physical protection, certain pastoralist groups have been targeted comparatively more successfully by the armed groups (mainly the jihadists). This not only threatens social cohesion but fuels resentment towards increasingly stigmatised nomadic populations.

Conclusions

Armed groups are engaged in the ‘progressive colonisation’ of forestry and mining resources. Therefore, forest enclaves have fallen into the hands of armed groups, with the present state of affairs in the Point Triple Area as a case in point. The violence arising from the establishment of armed groups in these areas, combined with neglect and political mismanagement on the part of the national authorities in Burkina Faso, Niger and Benin, has resulted in a situation where certain sections of the local population are being recruited into the armed groups, while other sections are seeking to form civil militias in order to offer resistance. If social cohesion is to be preserved and further violence averted, considerable work is required to address the injustices suffered by pastoralists, fishermen and all those who depend on forest economies and biodiversity.

Policy recommendations

- National authorities should provide further support and coordination for initiatives being pursued by local populations and ‘self-defence militias’ aimed at mitigating the threat of non-state armed groups. Such initiatives include making forest villages inaccessible to motorcycles (the main means of transport for armed groups), and the creation of forest tunnels/corridors to hide threatened native populations.

- State armed forces from all three countries in the ‘point triple’ should be mobilised and coordinated to protect affected populations. In this regard, following the death of forest rangers in the ‘point triple’ area on 8 February 2022, the President of Benin launched an ‘internal response plan

External link, opens in new window.’, which involves a joint military operation with Burkina Faso and Niger aimed at dismantling the armed and criminal groups threatening this part of West Africa.

External link, opens in new window.’, which involves a joint military operation with Burkina Faso and Niger aimed at dismantling the armed and criminal groups threatening this part of West Africa. - Burkina Faso, Benin and Niger should, in collaboration, re-adopt an integrated and inclusive approach to forest ecology and cross-border security in order to address the new land pressures in W Park, which are contributing to a rise in violence and collapse in mutual trust between communities.

- National authorities, backed by international partners, should pursue measures aimed at strengthening social cohesion between and among communities in Burkina Faso, Benin and Niger, thereby defusing factors driving insurgency among pastoralists, fishers and others, and restoring mutual trust. This should incorporate broad consultations with local populations (especially the self-defence groups), and an inclusive approach that seeks to end stigmatisation of particular communities.

NAI Policy Notes are a series of research-based briefs on relevant topics, intended for strategists and decision makers in foreign policy, aid and development. They aim to inform and generate input to the public debate and to policymaking. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute. The quality of the series is assured by internal peer-review processes and plagiarism-detection software.

About the author

- Papa Sow is a senior researcher at the Nordic Africa Institute. His research focuses on population dynamics and migration in West Africa, particularly Senegal, The Gambia, Benin and Niger, with special links to climate variability and uncertainties.

Further reading

The NAI policy notes series is based on academic research. For further reading on this topic, we recommend the following titles:

- Brottem, Leif (2022). The Growing Threat of Violent Extremism in Coastal West Africa

External link, opens in new window.. Washington DC: Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

External link, opens in new window.. Washington DC: Africa Center for Strategic Studies. - de Bruijne, Kars (2021). Laws of Attraction : Northern Benin and risk of violent extremist spillover

External link, opens in new window.. The Hague: Conflict Research Unit of Clingendael.

External link, opens in new window.. The Hague: Conflict Research Unit of Clingendael. - KAS Regional Programme Political Dialogue West Africa (PDWA) and Promédiation (2021). North of the countries of the Gulf of Guinea : The new frontier for jihadist groups? Kondrad Adenauer Stiftung (KAS).

- Lanzano, Cristiano; Luning, Sabine and Ouédraogo, Alizèta (2021). Insecurity in Burkina Faso – beyond conflict minerals: the complex links between artisanal gold mining and violence

External link, opens in new window.; (NAI Policy Notes, 2021:3). Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

External link, opens in new window.; (NAI Policy Notes, 2021:3). Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet. - Michelot, Agnès and Ouedraogo, Boubacar (2009). Aires Protégées transfrontalières: le cadre juridique de la réserve de biosphère transfrontalière du W (Bénin, Burkina Faso, Niger)

External link, opens in new window.; IUCN-EPLP No 81.

External link, opens in new window.; IUCN-EPLP No 81. - Pellerin, Mathieu et al (2021). Entendre la voix des éleveurs au Sahel et en Afrique de l'Ouest : Quel avenir pour le pastoralisme face à l'insécurité et ses impacts?

External link, opens in new window. ; Réseau Billital Maroobé (RBM).

External link, opens in new window. ; Réseau Billital Maroobé (RBM).

How to refer to this policy note:

Sow, Papa (2022). Counter-terrorism has to be trans-border and address root causes : Joint efforts key as jihadist violence spills over into Burkina Faso, Benin and Niger. NAI Policy Notes, 2022:6. Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:nai:diva-2713 External link.

External link.