Attacks on scholars a threat to democracy in Africa

The link between decreased academic freedom and the stagnation of democracy

Kampala, 18 May 2020. Ugandan scholar and activist Stella Nyanzi arrested by police officers as she organised a protest. Photo Sumy Sadurni, AFP.

The percentage of attacks on higher education is higher in Africa than in any other region. And with Covid lockdowns, the academic freedom at African universities has been challenged even further. Given the strong links between academic freedom and democracy, organisations working with democratic development in Africa should take action to

support and protect scholars at risk.

By Esther Kariuki, Hajer Kratou and Liisa Laakso

Academic freedom refers to the right of universities and individual scholars to conduct research, to teach and to communicate, even on matters that may be politically sensitive, without being targeted for suppression. The Kampala Declaration on Intellectual Freedom and Social Responsibility further highlights a reciprocal social responsibility. Academia has to be committed to adhere to research ethics, truth and objectivity.

Threats are on the rise

Threats to academic freedom, violent attacks on the higher education community including scholars, students, staff and institutions, are on the rise globally. In a 2017 statement External link, opens in new window., the European Association of Development Research and Training Institutes (EADI), raised alarm on incidents of infringement of scholars’ human rights within and outside of Europe, stressing its global nature. Recent trends in several European countries

External link, opens in new window., the European Association of Development Research and Training Institutes (EADI), raised alarm on incidents of infringement of scholars’ human rights within and outside of Europe, stressing its global nature. Recent trends in several European countries External link, opens in new window. suggest narrowing academic space through regulatory restrictions and limitations. Social media all over the world provide platforms for a fast spreading of hate speech affecting researchers working on issues that have become politically sensitive like migration, racism, climate change or even vaccinations.

External link, opens in new window. suggest narrowing academic space through regulatory restrictions and limitations. Social media all over the world provide platforms for a fast spreading of hate speech affecting researchers working on issues that have become politically sensitive like migration, racism, climate change or even vaccinations.

The Scholars at Risk (SAR) External link, opens in new window. network identifies, assesses and tracks attacks on academic freedom through its Academic Freedom Monitoring Project

External link, opens in new window. network identifies, assesses and tracks attacks on academic freedom through its Academic Freedom Monitoring Project External link, opens in new window.. SAR is a global network of institutions and individuals, operating at 500 universities in 40 countries, with the goal of promoting academic freedom and protecting those researchers whose lives or jobs are under threat. The backing towards this goal is gaining traction. Among the members of SAR are higher education institutions from all the Nordic countries with the Icelandic

External link, opens in new window.. SAR is a global network of institutions and individuals, operating at 500 universities in 40 countries, with the goal of promoting academic freedom and protecting those researchers whose lives or jobs are under threat. The backing towards this goal is gaining traction. Among the members of SAR are higher education institutions from all the Nordic countries with the Icelandic External link, opens in new window. and Danish

External link, opens in new window. and Danish External link, opens in new window. ones joining in 2017 and 2019 respectively. Norway

External link, opens in new window. ones joining in 2017 and 2019 respectively. Norway External link, opens in new window. has hosted around 30 at-risk scholars in its universities since 2011. Education funding agencies in Sweden

External link, opens in new window. has hosted around 30 at-risk scholars in its universities since 2011. Education funding agencies in Sweden External link, opens in new window. and Finland

External link, opens in new window. and Finland External link, opens in new window. have made commitments to fund institutions to host at-risk scholars. In November 2021, Finland marked its first Scholars at Risk Finland (SARF) Day

External link, opens in new window. have made commitments to fund institutions to host at-risk scholars. In November 2021, Finland marked its first Scholars at Risk Finland (SARF) Day External link, opens in new window., with an event advocating for academic freedom.

External link, opens in new window., with an event advocating for academic freedom.

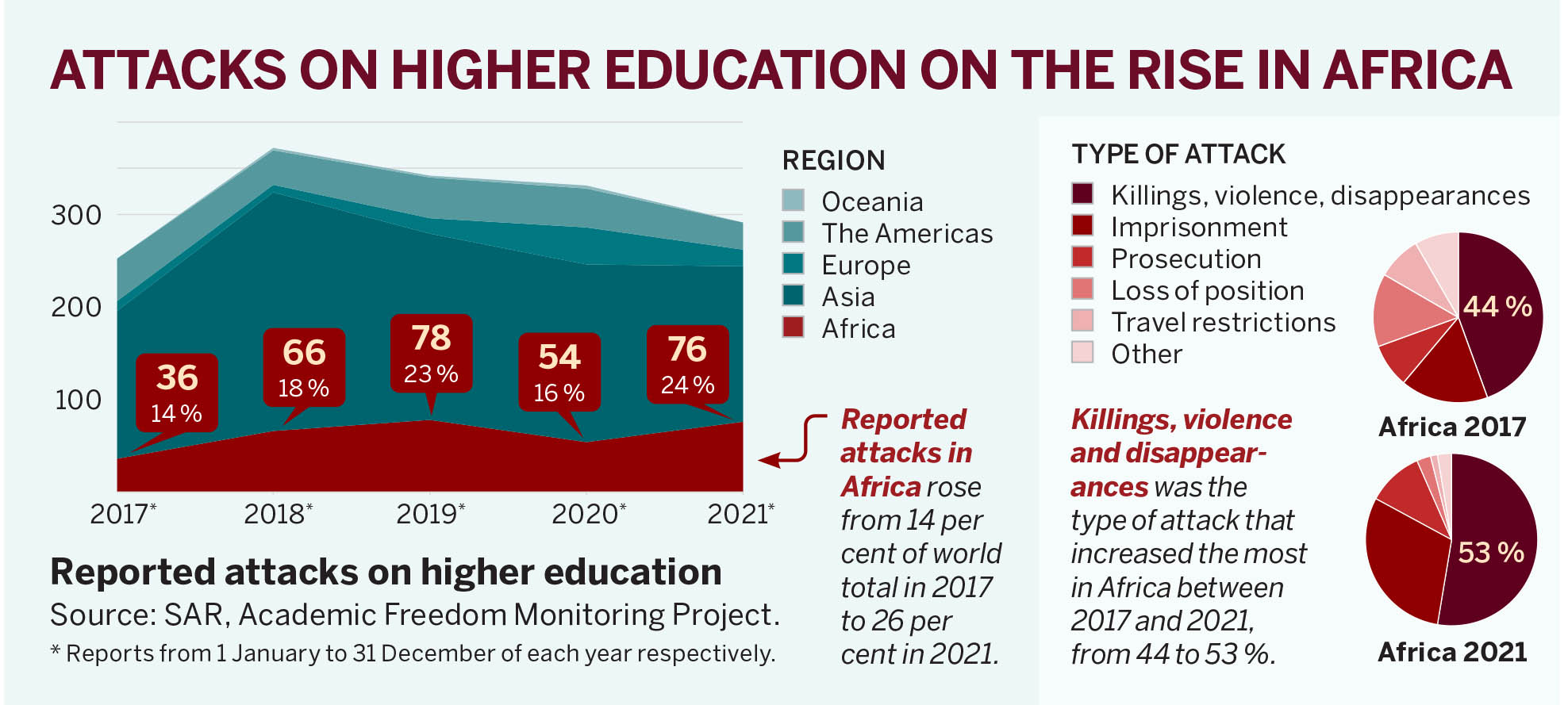

In 2021 SAR recorded 285 reported attacks on higher education and scholars working in higher education across the world. 76 of these were in African countries. Such attacks could involve: killings, disappearances, wrongful imprisonments or detention, prosecutions, restrictions on travel and retaliatory dismissal, loss of position or expulsion from study.

Scholars were among those at the forefront in advocating against injustices exposed by the Covid-19 pandemic. Ugandan scholar and activist Stella Nyanzi was arrested and charged External link, opens in new window. with inciting violence, because she led a demonstration outside the prime minister’s office. The protest followed an earlier petition that had called for the distribution of food relief and face masks, and for the release of prisoners held for allegedly violating measures to contain the spread of Covid-19. In Egypt, four members of the intellectual community – two professors, a human rights activist and a novelist – were also arrested after holding a protest demanding that the state take measures to guard against Covid outbreaks in prison.

External link, opens in new window. with inciting violence, because she led a demonstration outside the prime minister’s office. The protest followed an earlier petition that had called for the distribution of food relief and face masks, and for the release of prisoners held for allegedly violating measures to contain the spread of Covid-19. In Egypt, four members of the intellectual community – two professors, a human rights activist and a novelist – were also arrested after holding a protest demanding that the state take measures to guard against Covid outbreaks in prison.

SAR has also recorded several attacks unrelated to the pandemic, highlighting the persistent nature of the clampdown on academic freedom. A PhD candidate and political activist from South Sudan was arrested in July 2018 External link, opens in new window. and charged with treason. In 2020, he fled with his family to the United States, alleging that the South Sudanese president had ordered his execution or abduction in neighbouring Kenya. In Nigeria, a political science lecturer and a university administrator were arrested for protesting

External link, opens in new window. and charged with treason. In 2020, he fled with his family to the United States, alleging that the South Sudanese president had ordered his execution or abduction in neighbouring Kenya. In Nigeria, a political science lecturer and a university administrator were arrested for protesting External link, opens in new window. on social media about unpaid salaries: the police alleged that they had insulted the vice-chancellor of the university. Targeted violent attacks have also been reported, including the kidnap and beating

External link, opens in new window. on social media about unpaid salaries: the police alleged that they had insulted the vice-chancellor of the university. Targeted violent attacks have also been reported, including the kidnap and beating External link, opens in new window. of a student leader and opposition party member in Burundi. SAR has also noted the use of excessive and sometimes lethal force against student expression or to contain protests in the Democratic Republic of Congo

External link, opens in new window. of a student leader and opposition party member in Burundi. SAR has also noted the use of excessive and sometimes lethal force against student expression or to contain protests in the Democratic Republic of Congo External link, opens in new window., Nigeria

External link, opens in new window., Nigeria External link, opens in new window., Kenya

External link, opens in new window., Kenya External link, opens in new window., Liberia

External link, opens in new window., Liberia External link, opens in new window. and Sudan

External link, opens in new window. and Sudan External link, opens in new window., among others.

External link, opens in new window., among others.

Diminishing academic space is being witnessed even in countries such as Ghana where university autonomy has strong roots. The Universities Teachers of Association of Ghana (UTAG) continues to fight against the Public Universities Bill that is regarded as a legislative attack on academic freedom External link, opens in new window.. Under the proposed law, the president has power to appoint university Chancellors

External link, opens in new window.. Under the proposed law, the president has power to appoint university Chancellors External link, opens in new window. although the Ghanaian constitution provides that the Chancellor should be appointed by the university governing council. Additionally, the bill increases government representation in the university councils and requires that universities seek prior approval from the Minister for Education before entering into agreements with institutions within or outside the country. Such clauses have triggered concerns of political interference in the management of universities that would negatively impact their autonomy. The bill was suspended in December 2020 during the election period but fears loom that the government may seek to re-introduce it.

External link, opens in new window. although the Ghanaian constitution provides that the Chancellor should be appointed by the university governing council. Additionally, the bill increases government representation in the university councils and requires that universities seek prior approval from the Minister for Education before entering into agreements with institutions within or outside the country. Such clauses have triggered concerns of political interference in the management of universities that would negatively impact their autonomy. The bill was suspended in December 2020 during the election period but fears loom that the government may seek to re-introduce it.

Links between education and democracy

Higher education supports democracy but it does not of itself introduce or consolidate a democratic political system. That is, high levels of education in a given country do not guarantee that the country will have a strong democracy. However, research shows that the cognitive skills gained through education can improve awareness and understanding of politics thereby fostering pro-democracy attitudes.

University education, particularly in the social sciences and humanities, promotes critical reasoning and a culture of engagement. Scholars, then, can advise or confront those in power, challenge injustices or fight for change. Furthermore, higher education transcends the boundaries of learning institutions to reach even those who have not been educated in them. But education can only achieve such a democratic impact if the freedom of scholars or students to produce and relay knowledge is protected, respected and employed.

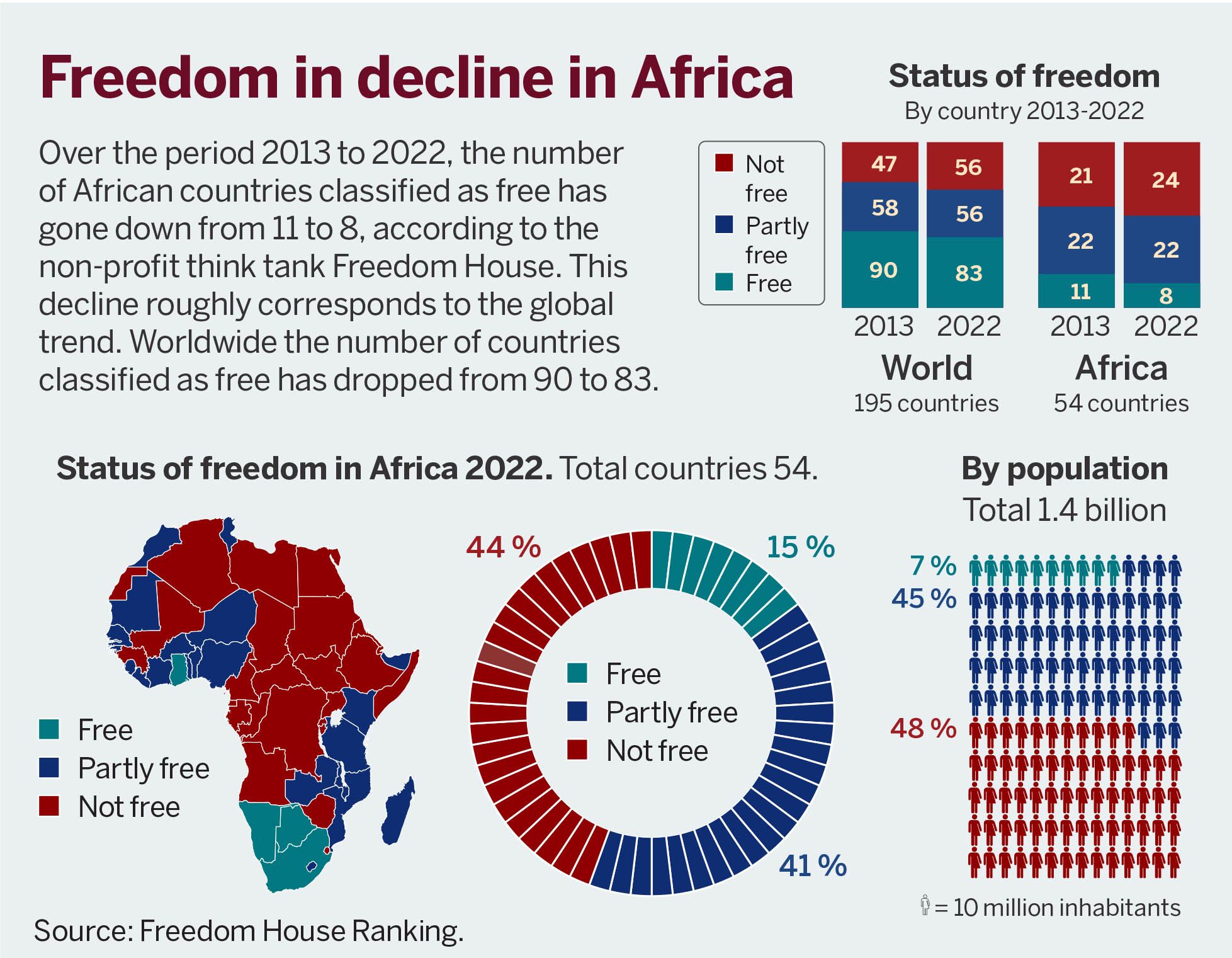

Signals of democratic stagnation

African countries have transitioned to formal multiparty democracy External link, opens in new window. in an arguably short period. Before 1990, single-party state political systems were commonplace, and only a few countries had introduced multiparty politics. By 1995, however, political pluralism had become the norm: 23 formerly single-party states held multiparty elections between 1989 and 1994. Although the democratic transition was widespread, democratization varied, with some countries succeeding, while others remained politically volatile.

External link, opens in new window. in an arguably short period. Before 1990, single-party state political systems were commonplace, and only a few countries had introduced multiparty politics. By 1995, however, political pluralism had become the norm: 23 formerly single-party states held multiparty elections between 1989 and 1994. Although the democratic transition was widespread, democratization varied, with some countries succeeding, while others remained politically volatile.

Today, international sources such as the Afrobarometer surveys of public opinion on the level of democracy still present a heterogeneous picture of democracy in Africa. There have been gains, for example in Ghana, which is rated as ‘free’ by Freedom House External link, opens in new window. and scores well on electoral democracy indicators, even though it has a history of military rule. On the other hand, in Senegal

External link, opens in new window. and scores well on electoral democracy indicators, even though it has a history of military rule. On the other hand, in Senegal External link, opens in new window., a country that for a long time was a democratization success story, opposition politicians were excluded from the ballot before the 2019 election.

External link, opens in new window., a country that for a long time was a democratization success story, opposition politicians were excluded from the ballot before the 2019 election.

Some current issues across the continent signal what may be seen as a stagnation of democratization. One cause for concern is the quality of elections, which is a vital indicator of democracy. Electoral violence may be common after a country undergoes a major political transition, but the ensuing elections are expected to be peaceful. However, approximately half of African elections are marred by violence, whereas the proportion in the world generally is a fifth.

Another issue relates to the concentration of power in the executive arm of government and the accountability of the executive. Cases of abuse of power by the executive are on the increase. In what are known as ‘constitutional coups External link, opens in new window.’, efforts are made to remove constitutionally mandated limits on the number of terms that a head of state can serve. For instance, in 2008, the constitution of Cameroon was amended to allow the incumbent president to run for another term, as well as to grant him immunity from prosecution for crimes committed while in office. Elsewhere, in Burundi, Chad, Togo, Egypt, Rwanda and Uganda, constitutional amendments have been enacted to eliminate the two-term limit for a head of state.

External link, opens in new window.’, efforts are made to remove constitutionally mandated limits on the number of terms that a head of state can serve. For instance, in 2008, the constitution of Cameroon was amended to allow the incumbent president to run for another term, as well as to grant him immunity from prosecution for crimes committed while in office. Elsewhere, in Burundi, Chad, Togo, Egypt, Rwanda and Uganda, constitutional amendments have been enacted to eliminate the two-term limit for a head of state.

Measuring the impact of academic freedom

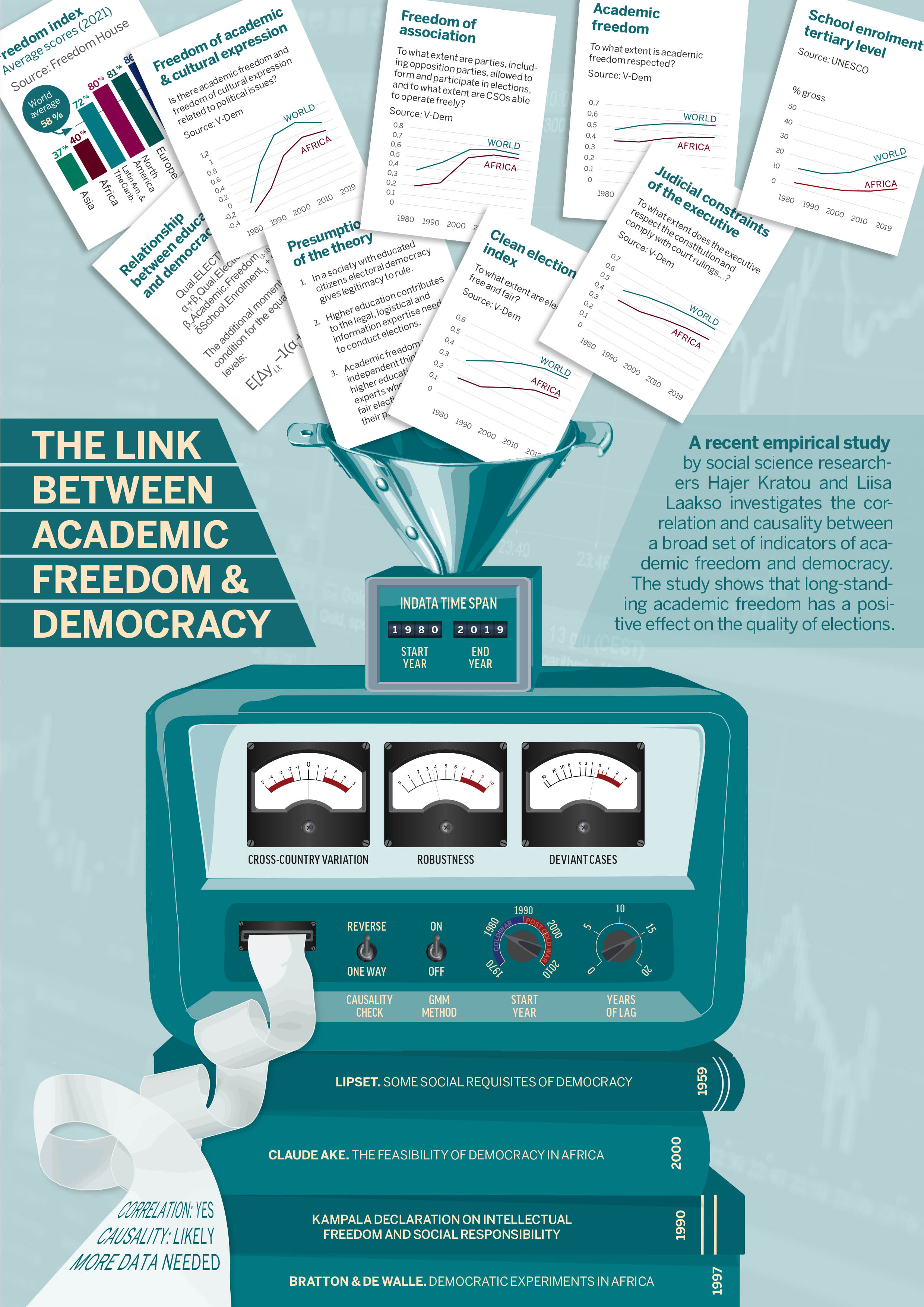

While there is no single explanation for the variation in the level of democracy between countries, the democratic role of education does offer some fresh insights. The relationship between education and democracy is not direct, but is mediated by factors that influence both education and democracy.

Academic freedom is one such aspect of higher education that can be firmly linked to gains in democracy. In a study published in 2021 External link, opens in new window., economist Hajer Kratou and political scientist Liisa Laakso isolated academic freedom, in order to measure whether and how it impacts democracy. To measure democracy and academic freedom, they used two indicators from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem)

External link, opens in new window., economist Hajer Kratou and political scientist Liisa Laakso isolated academic freedom, in order to measure whether and how it impacts democracy. To measure democracy and academic freedom, they used two indicators from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) External link, opens in new window. database: the clean elections index and the academic freedom index. They estimated the effect that academic freedom in the democratic transition period of 1980–1989 had on democracy in the subsequent post-Cold War period of 1990–2019.

External link, opens in new window. database: the clean elections index and the academic freedom index. They estimated the effect that academic freedom in the democratic transition period of 1980–1989 had on democracy in the subsequent post-Cold War period of 1990–2019.

The researchers concluded that academic freedom does have a strong and positive impact on the quality of elections, but that this impact needs time to make itself felt: a five-year period of stable academic freedom had less democratic impact than a ten-year period. University education and conducting research are time-consuming, after all. The result remained constant even when indicators of democracy that measure executive accountability were used. In summary, years of a high degree of academic freedom support the quality of subsequent elections and the accountability of the executive – i.e. democracy. African countries that had a higher level of academic freedom before and around the time of their democratic transition later had higher levels of democracy.

The study also pointed at other factors that affect democracy. The impact of academic freedom was, for instance, greater in lower-income than in middle- and upper-income countries. Other researchers have also noted that education appears to have a greater effect at lower income levels. Emigration, too, has been found to drive democratization: countries with more people living abroad have better democratic outcomes, which serves to emphasize the diaspora’s role in knowledge transfer and awareness enhancement, as well as its contribution to civil society in the home country. A 2020 qualitative study External link, opens in new window. by Laakso highlights that researchers who have connections abroad are perceived as being able to be more critical than those working exclusively in their home countries.

External link, opens in new window. by Laakso highlights that researchers who have connections abroad are perceived as being able to be more critical than those working exclusively in their home countries.

Policy recommendations

- National bodies facilitating and monitoring universities such as research councils and research quality assurance agencies should develop policies and criteria to secure academic freedom. The policies should be bolstered by mechanisms for protecting scholars and institutions and holding authorities accountable for securing academic freedom.

- Regional academic organisations and networks such as the Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA) and the African Studies Association of Africa (ASAA), among others need resources to support their members to build safe working conditions for their staff and students alike.

- International academic networks should support at-risk scholars through temporary positions or fellowships. Host institutions should promote measures to support smoother immigration processes for the visiting scholars. The fellowships or positions should be offered remotely in cases where travel is not possible.

- Development cooperation agencies, including Nordic government actors, should recognise the importance of academic freedom in research and higher education, including mobility within and outside Africa, for sustainable development. As the effect of higher education on democracy takes time, financial support towards these goals should be long-term.

NAI Policy Notes is a series of research-based briefs on relevant topics, intended for strategists, analysts and decision makers in foreign policy, aid and development. They aim to inform public debate and generate input into the sphere of policymaking. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute.

About the authors

- Esther Kariuki is a master graduate in international development from Lund University, Sweden. She has worked within advocacy and research in Kenya and Sweden.

- Hajer Kratou is an economist at Ajman University in the United Arab Emirates. Her research is on migrants’ remittances, foreign direct investments and financial flows.

- Liisa Laakso is a senior researcher at the Nordic Africa Institute. Her research is on world politics, international development cooperation and the democratization of Africa.

Further reading

The NAI policy notes series is based on academic research. For further reading on this topic, we recommend the following titles:

- Hajer Kratou and Liisa Laakso (2021). The impact of academic freedom on democracy in Africa

External link, opens in new window.. Journal of Development Studies.

External link, opens in new window.. Journal of Development Studies. - Liisa Laakso (2020). Electoral violence and political competition in Africa

External link, opens in new window.. In Nic Cheeseman (ed.), The Oxford Encyclopedia of African Politics. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 552–563,

External link, opens in new window.. In Nic Cheeseman (ed.), The Oxford Encyclopedia of African Politics. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 552–563, - Liisa Laakso (2020). Academic mobility as freedom in Africa

External link, opens in new window.. Politikon, 47(4),

External link, opens in new window.. Politikon, 47(4), - Liisa Laakso (2021). The social science foundations of public policy in Africa

External link, opens in new window.. In Gedion Onyango (ed.), Routledge Handbook of Public Policy and Administration in Africa. New York: Routledge, p. 23–33,

External link, opens in new window.. In Gedion Onyango (ed.), Routledge Handbook of Public Policy and Administration in Africa. New York: Routledge, p. 23–33, - Liisa Laakso and Esther Kariuki. Political science knowledge and electoral violence: Experiences from Kenya and Zimbabwe (forthcoming).

How to refer to this policy note:

Kariuki, Esther; Kratou, Hajer and Laakso, Liisa (2022). Attacks on scholars a threat to democracy in Africa : The link between decreased academic freedom and stagnation of democracy, NAI Policy Notes 2022:4, Uppsala: The Nordic Africa Institute. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:nai:diva-2681 External link, opens in new window.

External link, opens in new window.