Is Doumbouya sincere about returning democracy to Guinea?

Supporters of junta leader, Colonel Mamady Doumbouya, stand around a poster of him at the Peoples Palace in Guinean capital Conakry, on September 11, 2021. Photo: John Wessels/AFP

Guinea’s strongman Col. Mamady Doumbouya, who took power in a coup last year, has rejected calls from regional bloc ECOWAS to hold elections by the end of March. Is he simply making excuses to cling on to power? Not necessarily, says NAI Senior Researcher Jesper Bjarnesen.

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has demanded that Guinea hold elections within six months of the September 2021 coup that removed the country’s president, Alpha Condé, from power.

However, according to the new Guinean regime, elections can only take place after drafting a new constitution and reforming the country’s judicial and administrative systems.

The coup’s leader, Doumbouya, a colonel in the Guinean army, in October 2021 was sworn in as interim president, promising “free, credible and transparent” elections. Doumbouya appointed well-respected former UN diplomat Mohamed Béavogui as prime minister. A transitional assembly – known by its French acronym CNT – with members from political parties and associations, was tasked with drafting the new constitution and suggesting a date for a return to civilian rule.

“What we are seeing in Guinea may very well be genuine steps to prepare for elections. Or they could simply be an excuse used by the military junta to remain in power. The truth is that we don’t know”, Bjarnesen says.

Jesper Bjarnesen. Photo: Mattias Sköld

It is deeply problematic that, with the constitution out of play as a result of the coup, the fate of Guinean democracy is in the hands of a very small clique, according to Bjarnesen.

Many Guineans seem to sympathise with the idea Doumbouya has put forward that it is necessary to “refound the state” before elections can be held, according to NAI Senior Researcher Papa Sow.

“There is a widespread perception that [President Alpha] Condé broke the system when he made constitutional changes which allowed him to win a third term in office in 2020. There is also a lot of anger and frustration over rampant corruption within the public administration and military”, Sow says.

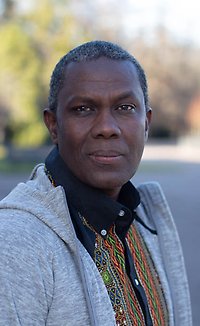

Papa Sow. Photo: Mattias Sköld

Guineans are also suspicious about ECOWAS, which is perceived as a “presidents’ club”, an organisation led by heads of states who in many cases have questionable democratic records themselves, according to Sow.

Bjarnesen says that rushing into holding elections, simply to meet expectations by the international community, would come with considerable risks.

“When you push for elections at a point where the system is not ready or where there are unreconciled divisions within the country that go beyond competitive politics, then elections can be a trigger for more violence and destabilisation”.

Old structural problems not dealt with are likely to come back and haunt a new government after elections, Bjarnesen adds.

According to Bjarnesen, the situation in post-coup Guinea bears similarities with that in regional neighbour Burkina Faso in 2014, where a popular uprising forced out the president, Blaise Compaoré. In both cases, the leaders had changed the constitution to stay in power, which angered large parts of the population before the army intervened.

However, power relations between military and civilian actors appear to be different in the two cases, Bjarnesen says.

“In Burkina Faso, Yacouba Isaac Zida, the military officer who briefly stepped in as acting head of state after Compaoré had been removed from power, was pressured by well-organised political and civil society groups. They insisted that the transitional council be led by a civilian and soon forced Zida to make way for a civilian interim president”.

In Guinea, Doumbouya appears to be clearly in charge, firmly holding on to the position of interim president and head of the CNT, according to Bjarnesen.

“There is very little questioning of Doumbouya’s authority, and that leaves the door open for him to dissolve the CNT and take the country in a different direction on a whim”.

If multiparty politics is reintroduced in Guinea, as the interim government has promised, it is uncertain what the political playing field will look like, Bjarnesen continues.

“What will happen to the former ruling party, Rally of the Guinean People [RPG]? They have several well-known figures who could run [for president] but the question is what state the party is in after the fall of Alpha Condé”.

Veteran opposition leader Cellou Dalein Diallo, of the Union of Democratic Forces of Guinea (UFDG), who appears to have the most consolidated electoral base, is the favourite to win a future presidential election, according to Bjarnesen.

However, a scenario where the current leader, Doumbouya, reinvents himself as a politician is also possible – albeit constitutionally problematic – in which case old political power structures may be turned upside down.

“Doumbouya is very popular. He seems to have a taste for political power and enjoys being a public figure. Doumbouya is certainly not a run-of-the-mill military officer – he has had a very quick rise in the military hierarchy. He may not want to lose his influence over which direction the country should take”, Bjarnesen concludes.

TEXT: Mattias Sköld

Background: Republic of Guinea

Guinea has a long history of military coups d'état and authoritarian rule. After gaining independence from France in 1958, Guinea first aligned itself with the USSR and later moved towards a Chinese model of socialism. Under the presidency of Ahmed Sékou Touré, Guinea became a one-party state where dissidents were imprisoned and the media stifled.

After Touré’s death in 1984, Col. Lansana Conté seized power in a bloodless coup and assumed the presidency. In 1992, Conté announced a return to civilian rule, with a presidential poll in 1993, followed by elections to parliament in 1995. Despite his stated commitment to democracy, Conté’s grip on power remained tight.

After Conté’s death in 2008, Capt. Moussa Dadis Camara seized control in a coup. Protests against the coup turned violent and on 28 September 2009 157 people were killed when the junta ordered soldiers to attack protesters. The soldiers went on a rampage of rape, mutilation and murder. Camara was later shot by an aide and fled the country to seek medical care.

After a return to civilian rule, veteran opposition leader and professor of public law Alpha Condé won the 2010 election. Condé promised democratic restoration and ethnic reconciliation. The adoption of a new constitution in March 2020 that allowed Condé to sidestep the country’s two-term limit provoked mass protests. On 5 September 2021, less than a year into Condé’s third presidential term, Col. Mamady Doumbouya seized power in a coup.