Harmonising land privatisation with customary rights

A middle way for land rights formalisation in Zambia

Zambia, Western Province, November 2015. Road to Kaoma. Photo Marcel Crozet, ILO.

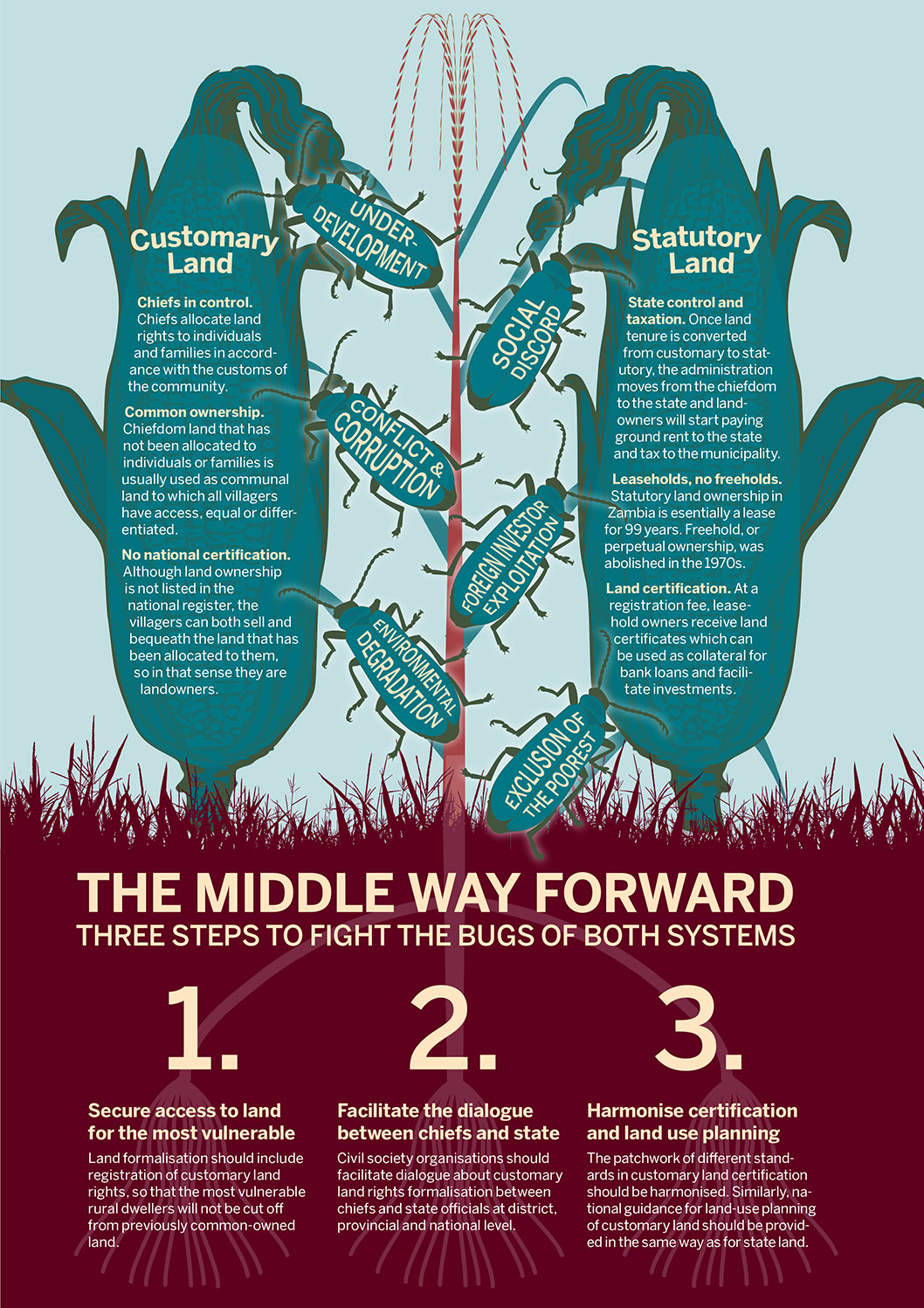

Many critics of customary land rights systems call for conversion of customary tenure to leasehold. This policy note argues for a middle way forward. By formalising the collective ownership of customary land in two levels, primary and secondary rights, instead of converting it to exclusively individual leasehold estates, Zambian authorities can enhance the rights of primary claimants, without excluding secondary land rights holders from their livelihood bases.

By Bridget Bwalya Umar, African Scholar Programme, the Nordic Africa Institute

When the Zambian government called a meeting of stakeholders in February 2018 to validate the draft national land policy, the chiefs invited walked out in protest External link, opens in new window. against some of the proposed changes relating to customary land administration. As the custodians and administrators of customary land in Zambia, they were displeased about what they considered to be attempts by the government to reduce the authority of chieftaincy over the land. Speaking on behalf of 288 chiefs representing all of Zambia’s ten provinces, the House of Chiefs chairperson, Chief Ngabwe, accused the government

External link, opens in new window. against some of the proposed changes relating to customary land administration. As the custodians and administrators of customary land in Zambia, they were displeased about what they considered to be attempts by the government to reduce the authority of chieftaincy over the land. Speaking on behalf of 288 chiefs representing all of Zambia’s ten provinces, the House of Chiefs chairperson, Chief Ngabwe, accused the government External link, opens in new window. of attempting to abolish the chieftaincy. ‘The chiefs’ objectives of the national land policy should be to protect the chieftaincy in Zambia, to uphold and preserve the customary land tenure in Zambia, we don’t want to copy anything from another country…to empower chiefs with the authority to issue customary land titles to provide legal protection to land owners of customary land like those under lease of tenure’, he said. The chiefs were supported in their walkout by opposition politician Saviour Chishimba, president of the United Progressive Party. He argued that the abolition of customary land tenure and the introduction of an open market system would only serve to cement the ongoing scramble for Zambia by the Chinese and other foreign nationals. The minister responsible for lands and natural resources, Jean Kapata, lamented that the move by the traditional leaders was surprising and sad. Traditional leaders command considerable political authority in Zambia. The government depends on them for the day-to-day management of customary areas and the implementation of development initiatives.

External link, opens in new window. of attempting to abolish the chieftaincy. ‘The chiefs’ objectives of the national land policy should be to protect the chieftaincy in Zambia, to uphold and preserve the customary land tenure in Zambia, we don’t want to copy anything from another country…to empower chiefs with the authority to issue customary land titles to provide legal protection to land owners of customary land like those under lease of tenure’, he said. The chiefs were supported in their walkout by opposition politician Saviour Chishimba, president of the United Progressive Party. He argued that the abolition of customary land tenure and the introduction of an open market system would only serve to cement the ongoing scramble for Zambia by the Chinese and other foreign nationals. The minister responsible for lands and natural resources, Jean Kapata, lamented that the move by the traditional leaders was surprising and sad. Traditional leaders command considerable political authority in Zambia. The government depends on them for the day-to-day management of customary areas and the implementation of development initiatives.

This outcry by the chiefs was not new. Ever since the ‘winds of change’ swept Kenneth Kaunda, Zambia’s first president, from office and heralded the neoliberal regime of Fredrick Titus Jacob Chiluba in 1991, the state had made paradigmatic land administration pronouncements, including a revised Lands Act in 1995. It included a provision for the conversion of land tenure from customary to leasehold: essentially a way of moving land administration from the chieftaincy to the state. After the promulgation of the Lands Act in 1995, chiefs complained that it aimed at reducing the amount of land held under customary land tenure, with the goal of eventually abolishing the institution of chieftaincy. Protests by the chiefs rekindled debates on the relevance of customary land in a modern Africa.

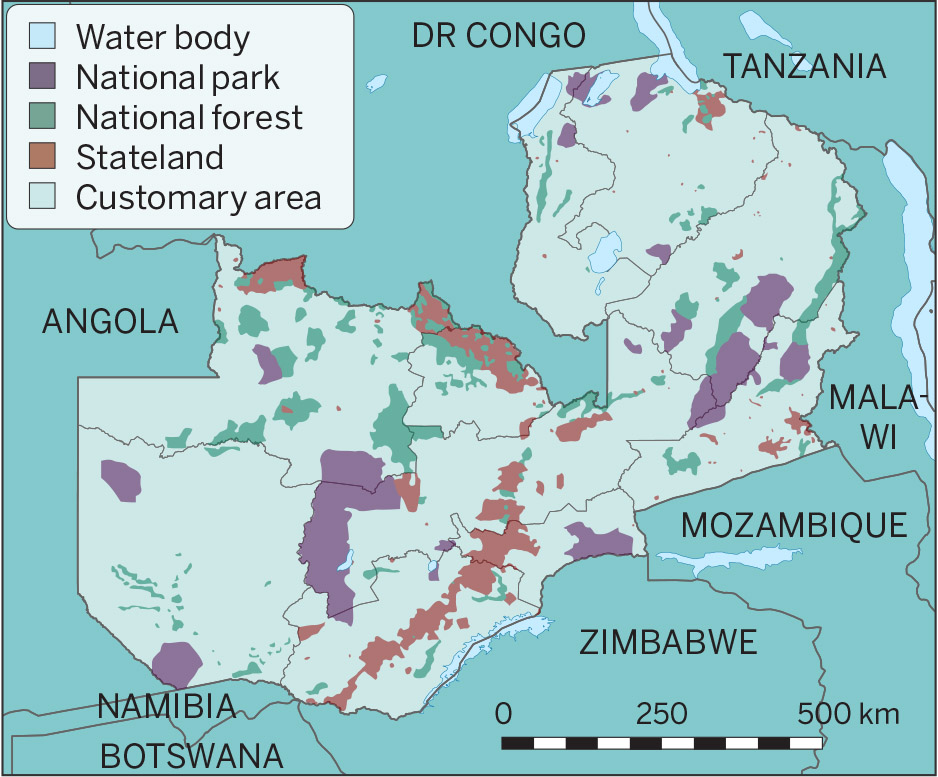

Land tenure categories in Zambia. National forests and parks are governed according to legal statutes, even when they are located on customary land. Source: Survey Department, Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources (data compiled 2022 by Garikai Membele, University of Zambia).

Supporters and critics of customary tenure

About two thirds of all uncultivated land in Sub-Saharan Africa – some 2.2 billion hectares – is under customary tenure. This is a set of rules, norms and practices for a particular community, and it governs how resources are accessed and owned. In Zambia, customary land ownership is not documented in the national land management system, as is the case with state land. Customary land claimants did not have any possibility to document their land rights until chiefs introduced land rights formalisation three years ago.

Supporters of customary land tenure systems argue that they provide low-cost access to land, offer communal management of natural resources and contribute to group identity for many rural dwellers. Customary regimes are better able to integrate cultural aspects, such as land inheritance practices, and provide communal rights to forests, rangelands, marshlands and other shared resources that are unsuited to individualised management External link, opens in new window..

External link, opens in new window..

Critics of customary tenure systems point out that they perpetuate inequality among particular groups of people, such as women, the youth and the economically disadvantaged. There are reports of traditional leaders using their power to seize control of community land for their own personal benefit External link, opens in new window..

External link, opens in new window..

In their joint Framework and Guidelines on Land Policy in Africa External link, opens in new window., the African Union, the UN Economic Commission for Africa and the African Development Bank acknowledge the disparities in land access between men and women in Africa. They argue that we need to deconstruct, reconstruct and reconceptualise existing land rights in ways that strengthen women’s access to land, while respecting family and other social networks.

External link, opens in new window., the African Union, the UN Economic Commission for Africa and the African Development Bank acknowledge the disparities in land access between men and women in Africa. They argue that we need to deconstruct, reconstruct and reconceptualise existing land rights in ways that strengthen women’s access to land, while respecting family and other social networks.

Customary land tenure systems are said to discourage investment in sustainable land management, because of the insecure tenure associated with them. A systematic review of literature by Higgins and colleagues (2018) found strong evidence for positive effects of land tenure security External link, opens in new window. on productive and environmentally beneficial agricultural investments and on female empowerment. The lack of investments and assumed tenure insecurity have been attributed to the informal nature of the way in which land rights are held under customary tenure systems. This has led to calls for land rights formalisation.

External link, opens in new window. on productive and environmentally beneficial agricultural investments and on female empowerment. The lack of investments and assumed tenure insecurity have been attributed to the informal nature of the way in which land rights are held under customary tenure systems. This has led to calls for land rights formalisation.

Formalisation without tenure conversion

Land rights formalisation is a process of identifying, adjudicating and registering land rights. A formal tenure system is one created by written rules and statutes. Several countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, including Malawi, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia have moved towards the formalisation of customary land rights. The rationale provided by the proponents of land rights formalisation is that ill-defined property rights inevitably lead to natural resource mismanagement.

Formalisation processes entail significant changes for rural dwellers who derive and enjoy the benefit of their land rights on the basis of customary norms and practices. Changes include a loss of secondary rights to natural resources and their products, and create unaffordable costs for many rural dwellers. Poor customary land rights claimants may not have the means to pay their share of formalisation costs. Landowners who convert from customary to leasehold tenure pay ground rents to the state and taxes to the local municipalities, and fees for permits to build and for any land-use changes. As state land administration is centralised, landowners have to travel to a provincial capital to have their title deeds processed. Furthermore, once tenure is converted from customary to leasehold, the land is lost from the chiefdom and becomes state land. Land held under the statutory leasehold tenure is administered by the central government through the Ministry of Lands, on the basis of common law. The House of Chiefs regards the resulting reduction in land under the control of traditional leaders as a threat to chieftaincy.

Some traditional leaders, scholars, development practitioners and certain sections of civil society in Zambia have called for formalisation without tenure conversion – that is, the documentation and recording of customary land rights. This is a middle way that avoids the costs and the criticisms of tenure conversion, while also addressing the constraints of undocumented land. As of 2019, 4 per cent of rural residents in Zambia had obtained customary land certificates External link, opens in new window., while 2.8 per cent had converted to leasehold tenure. The land held under customary tenure is governed by 288 chiefs, each of whom draws on the respective tribe’s norms, values and practices. This plethora of customary governance systems provides rights to different categories of people, based on tribal or clan customs. This is beneficial for those rural dwellers who depend on customary institutions to access land. In 2019, up to 95 per cent of rural dwellers

External link, opens in new window., while 2.8 per cent had converted to leasehold tenure. The land held under customary tenure is governed by 288 chiefs, each of whom draws on the respective tribe’s norms, values and practices. This plethora of customary governance systems provides rights to different categories of people, based on tribal or clan customs. This is beneficial for those rural dwellers who depend on customary institutions to access land. In 2019, up to 95 per cent of rural dwellers External link, opens in new window. reported that they had acquired their land through customary means.

External link, opens in new window. reported that they had acquired their land through customary means.

Some traditional leaders have been working in conjunction with non-governmental organisations to implement low-cost customary land rights formalisation programmes involving entire chiefdoms. The economies of scale that result from having every landowner in the chiefdom involved reduce the costs of formalisation for them.

More tenure security, less land sales and increased access to credit

A recent report External link, opens in new window. from the project Sustainable Agricultural Intensification Research and Learning in Africa (SAIRLA) looked at stakeholders’ perspectives on customary land certification in Eastern and Central Zambia. The report identified six key factors that most (or all) stakeholders perceived to be positively impacted by customary land rights formalisation: (1) enhanced land tenure security, (2) reduced land sales, (3) increased access to credit, (4) sustainable agricultural intensification, (5) fewer arbitrary land grabs and (6) better land-use planning

External link, opens in new window. from the project Sustainable Agricultural Intensification Research and Learning in Africa (SAIRLA) looked at stakeholders’ perspectives on customary land certification in Eastern and Central Zambia. The report identified six key factors that most (or all) stakeholders perceived to be positively impacted by customary land rights formalisation: (1) enhanced land tenure security, (2) reduced land sales, (3) increased access to credit, (4) sustainable agricultural intensification, (5) fewer arbitrary land grabs and (6) better land-use planning

Among the stakeholders studied in the SAIRLA report, there was unanimous agreement that customary land rights formalisation had significantly enhanced land tenure security and reduced land sales. One widow, whose views were echoed by others, said: ‘It is a good thing that has come because one can point that this is land that makes me be able to keep my children. I will not be evicted no matter.’ Land inheritance by sons and daughters was secured through land rights formalisation, as future competing claims from extended family members were obviated. Land sales fell substantially, as ‘fly-by-night’ land sales were curtailed. Land boundary disputes between neighbours were reduced.

The SAIRLA report also showed that the issuing of customary certificates in the wake of land rights formalisation led to increased access to credit – but not through banks and other formal financial institutions. Farmer cooperatives and local savings and credit cooperatives agreed to hold customary land as collateral when customary certificates were used. However, formal financial institutions, such as banks, would not accept customary certificates – apart from one bank in one chiefdom, after a memorandum of understanding was signed with the chief. The local recognition that came with customary land formalisation opened up access to credit for rural dwellers, who generally do not use banks and who face difficulty in accessing credit from formal financial institutions.

Sustainable agricultural intensification

According to the SAIRLA report, the use of conservation agriculture and agroforestry increased markedly after land rights formalisation. The effects on crop–livestock integration and tree conservation were mixed.

The collection of non-timber forest products was rampant before land rights formalisation, as untilled private lands were de facto open-access areas and overexploitation was an ever-present threat. After land rights formalisation, the appropriation of forest products from private lands was only possible with permission from the owners; meanwhile the practices of setting forest fires and making furrows to trap rodents in agricultural fields were nearly eliminated. The changed post-certification norms seem likely to have had a positive effect on forest resources conservation.

Fewer land grabs and better planning

Last but not least, the SAIRLA report concludes that land rights formalisation led to a reduction in land disputes and in arbitrary land grabs by traditional leaders. As one man put it: ‘Before, they [village headpersons] used to remove orphans from land. Now they will just be shown the certificates.’ According to another man, ‘Traditional land administration has been made easier. There are fewer land disputes.’ Thanks to the certification registers that were introduced with land rights formalisation, traditional leaders hold updated and comprehensive records about their subjects, which is an entry point for integrated land-use planning in conjunction with the local authorities. Despite the Urban and Regional Planning Act of 2015, which provides for collaborative planning in customary areas between local authorities and traditional leaders, there has been very little joint planning in customary areas. Traditional leaders have been wary of state-driven interventions in customary areas. Customary land rights formalisation provides an opportunity for traditional leaders to call in local authorities for advice on land-use planning, using information about the extent and status of land resources in their chiefdoms obtained from formalisation programmes.

Conclusions

Customary land rights formalisation can enhance land tenure security and the rights of primary claimants, such as wives, sons and daughters. It achieves relatively equitable outcomes, compared to the conversion of land tenure from customary to leasehold. However, increased access to formal credit is unlikely. Customary landowners remain reluctant to use their land holdings as collateral, for fear of losing the land in case of default, and financial institutions largely remain unwilling to recognise customary land certificates. Customary land rights formalisation is likely to lead to investment in tree and soil conservation at the farming household level and to a shift towards sustainable agricultural intensification. Demand for land from urbanites and investors has increased exponentially, necessitating land-use planning. Customary land rights formalisation provides an opportunity to include customary areas in regional integrated development plans, and to ensure that land use is planned and regulated.

Policy recommendations

- The government, traditional leaders and other stakeholders should continue to work towards low-cost customary land rights formalisation initiatives and include registration of customary land rights through municipal authorities.

- Regional and district planners should recognise customary land rights formalisation within the broader context of national land governance, by leveraging the Urban and Regional Planning Act of 2015, which provides for local authority involvement in land-use planning of customary areas.

- The government should scale up customary land rights formalisation programmes to all chiefdoms.

- Chiefdoms must harmonise the customary land certificates, in terms of the information contained therein.

- Civil society organisations should facilitate dialogue about customary land rights formalisation between chiefs and those state officials responsible for land administration at district, provincial and national level.

- The Ministry of Lands should include land-use planning measures for customary areas in its National Land Policy implementation plan to provide similar guidance on land-use planning as will be provided for state land.

NAI Policy Notes is a series of research-based briefs on relevant topics, intended for strategists, analysts and decision makers in foreign policy, aid and development. They aim to inform public debate and generate input into the sphere of policymaking. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute.

About the author

- Bridget Bwalya Umar, is a senior researcher on the Africa Scholars Programme at the Nordic Africa Institute (NAI). She has 14 years experience teaching natural resource governance and development at the University of Zambia. Her research is about land governance in rural and urban contexts, gender, food systems and climate resilience.

Further reading

The NAI policy notes series is based on academic research. For further reading on this topic, we recommend the following titles:

- Chitonge, H. & Umar, B.B. (eds). 2018. Contemporary Customary Land Issues in Africa: Navigating the contours of change

External link, opens in new window.. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

External link, opens in new window.. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. - Chitonge, H., Mfune, O., Umar, B. B., Kajoba, G. M., Banda, D. & Ntsebeza, L. (2017). Silent privatisation of customary land in Zambia: opportunities for a few, challenges for many

External link, opens in new window., Social Dynamics, 43:1, p. 82-102.

External link, opens in new window., Social Dynamics, 43:1, p. 82-102. - Nyanga, P. H., Umar, B. B. & Wakun’uma, W. L. (2020). Social Learning on Land equity: Stakeholders’ Perspectives on Customary land certification in Eastern and Central Zambia

External link, opens in new window.. SAIRLA.

External link, opens in new window.. SAIRLA.

How to refer to this policy note:

Umar, Bridget Bwalya (2022). Harmonising land privatisation with customary rights : A middle way for land rights formalisation in Zambia. (NAI Policy Notes, 2022:2). Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:nai:diva-2636 External link.

External link.