After the pandemic – an opening for tax reforms

Post-Covid taxation challenges across Africa

A money exchanger in the Somali capital Mogadishu. Photo Stuart Price, AU UN IST.

One of the most efficient ways of promoting long-term inclusive development is to ensure domestic financing through a stable, broad-based and fair tax system. At the present moment, as policy makers across the world are preparing post-pandemic policies, there is an opportunity to open the way to tax reform and to boost inclusive development in many African countries – provided the correct measures are chosen.

By Jörgen Levin, Senior Researcher, The Nordic Africa Institute

Domestic tax revenues offer a long-term source of financing for social security programmes, but only if the tax system is built both on the readiness of people to comply with their tax obligations and on their trust in the state. Even if tax revenue performance in African countries has improved significantly over the past two decades, the economic recession caused by the pandemic has taken its toll. In addition, many African countries temporarily extended the deadline for filing tax returns, reduced income tax rates and cut indirect taxes, in order to ease the tax burden during the pandemic. For example, in 2020 the parliament in Mozambique approved a value-added tax (VAT) exemption for inputs in the food-processing industry. Nigeria introduced a VAT exemption on food, medical and pharmaceutical products, and also waived import duties on medical equipment required for the treatment and management of Covid-19.

As societies gradually open up again and phase out Covid regulations, the tax authorities are reverting to the pre-pandemic tax structures – and are even introducing new taxes. In Kenya, the VAT rate is back to 16 per cent and the corporate profit tax rate has been raised to its pre-pandemic level of 30 per cent, following a temporary reduction to 25 per cent. In Ghana, a new Covid-19 health recovery fund is being paid for by increased fuel taxation. The revenue authorities have also stepped up their efforts to simplify tax payment procedures by swiftly moving over to digital platforms. For example, since mid-2021 all domestic taxpayers in Ghana have had to pay their taxes either using the tax authority’s online platform or at one of several designated banks. In early 2020, the Mozambican tax authorities announced the introduction of an electronic platform to allow for the e-filing of tax returns. And the tax authorities in Nigeria have also been encouraging taxpayers to use e-platforms to file their returns.

But even if governments do succeed in restoring revenue to pre-coronavirus levels, they will still be under pressure to improve revenue mobilisation further, in order to develop welfare systems that not only are prepared for future shocks similar to the Covid-19 pandemic, but that also support the Sustainable Development Goals agenda.

Uneven tax revenue performance

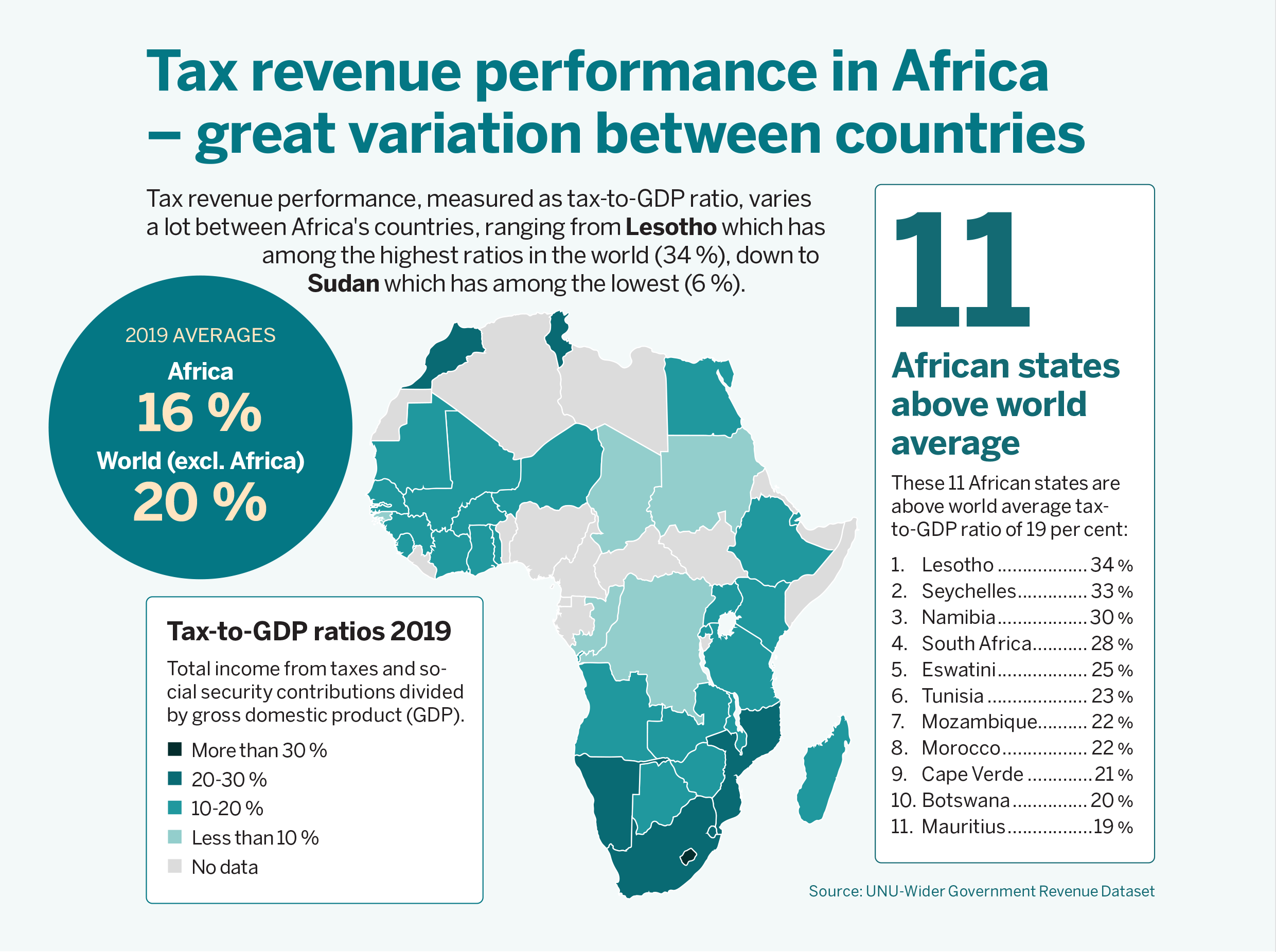

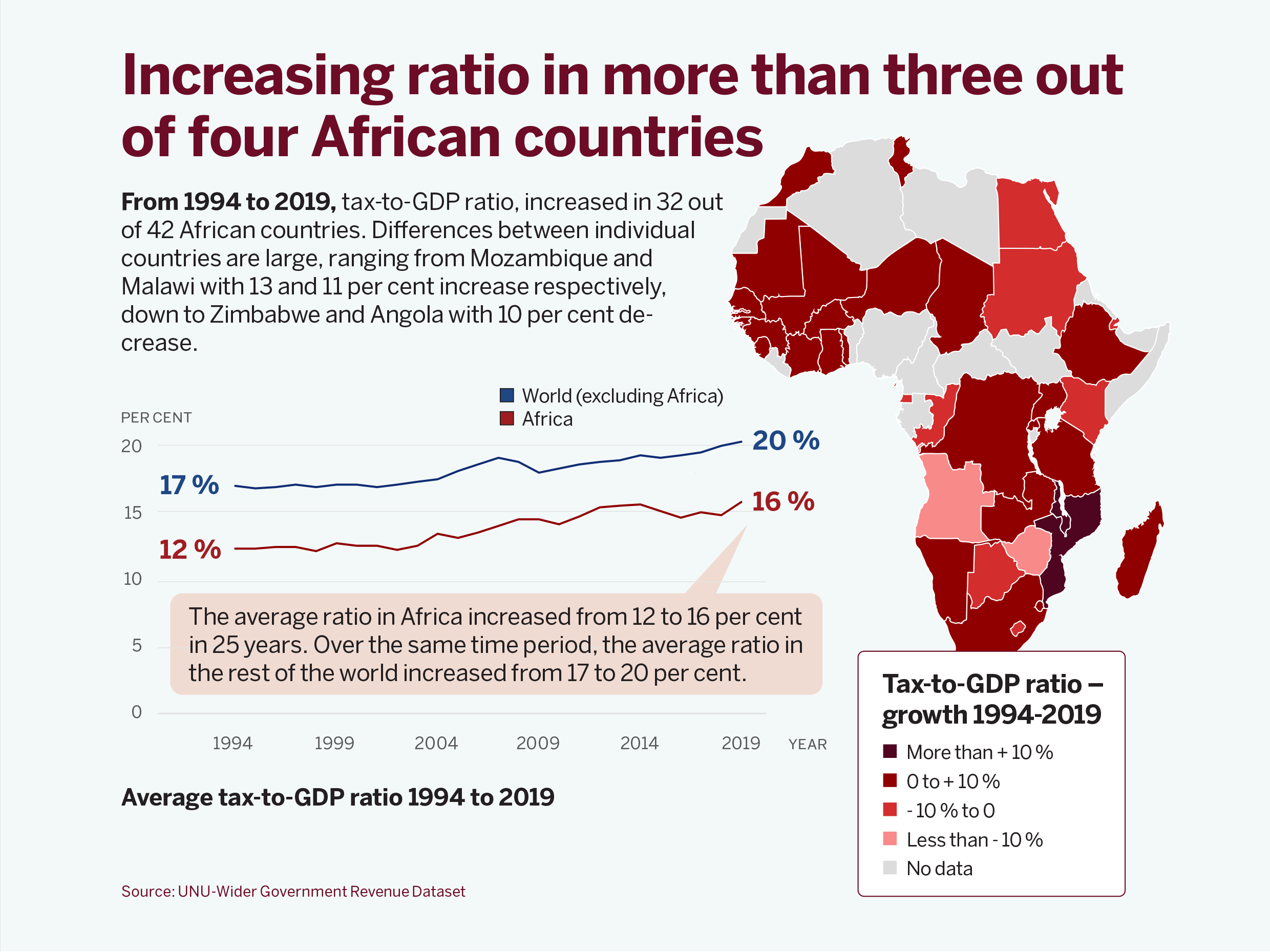

African countries are diverse in terms of both their economic structure and the political factors affecting them – whether the quality of their institutions or a weak sense of national identity, due to past policies and historical events. Some countries are going through internal conflict, while others are suffering long-term decline in both economic performance and governance. Unsurprisingly, tax revenue performance across Africa varies greatly. On the one hand, four African countries (Lesotho, Seychelles, Namibia and South Africa) feature among the top 20 countries globally; on the other hand, several of the bottom 20 countries in the world are also from Africa. There are also great variations in how the tax-to-GDP ratios have changed. For example, Mozambique has managed to increase its tax-to-GDP ratio by 14 per cent in 25 years, from around 8 per cent in the mid-1990s to close to 22 per cent in 2019.

However, countries that are economically dependent on natural resources have, to a large degree, seen fewer improvements in tax revenue performance. In countries such as South Sudan, Angola, Nigeria, Chad and Gabon, resource rents make up a significant share of government revenue, and tax revenue is less important. This creates severe fiscal challenges, as resource rents are volatile (since commodity prices fluctuate widely). For example, even though the Nigerian economy was facing economic difficulties before, Covid-19 – along with the sharp fall in oil prices – served to magnify its vulnerabilities, leading to a historic decline in growth and causing the government, for the first time since 2000, to ask for an emergency loan from the International Monetary Fund to avoid having to make large budget cuts. To reduce the fluctuations in revenue during booms and busts, resource-dependent countries need to diversify their revenue bases. However, this has turned out to be problematic, as countries that receive large resource rents are also likely to significantly reduce their domestic tax effort.

Challenges in building a fair tax system

Tax systems need to be fair, in terms of their design and implementation. While personal income tax (PIT) in African countries may be fair and progressive on paper, in reality that is not always the case. A major problem in analysing PIT in Africa is lack of data – only recently, and in only a few countries, have African tax authorities made registration data publicly available. Even then, it is hard to obtain a clear picture of whether income tax systems are progressive, as relatively few individuals are registered. For example, in Uganda around 10 per cent of the labour force is registered as paying tax. However, that does not necessarily mean that individuals are not paying taxes, as there is a myriad of tax-like payments at the local government level. With multilayer levels of different taxes, and sometimes duplication of the same tax, it is still a complicated task to find out what tax to pay. Afrobarometer data External link, opens in new window. show that, in most African countries, the majority of the population finds it difficult to ascertain what taxes or fees need to be paid. One way of avoiding multiple taxes and confusion among taxpayers would be to simplify the tax system, by streamlining central and local tax administrations into a single unified system.

External link, opens in new window. show that, in most African countries, the majority of the population finds it difficult to ascertain what taxes or fees need to be paid. One way of avoiding multiple taxes and confusion among taxpayers would be to simplify the tax system, by streamlining central and local tax administrations into a single unified system.

The tax authorities also need to focus their efforts on improving tax compliance, making sure that those supposed to pay actually do so. This applies to all individuals who are obliged to pay income tax, but especially to wealthy individuals. For example, according to an International Centre for Tax and Development (ICTD) case study from Uganda External link, opens in new window., the targeted auditing of wealthy individuals managed to increase revenue by USD 5.5 million within a year. Even if the amount of revenue is small in relation to total tax revenue, it still sends an important signal that rich individuals also have obligations as taxpayers and are subject to auditing.

External link, opens in new window., the targeted auditing of wealthy individuals managed to increase revenue by USD 5.5 million within a year. Even if the amount of revenue is small in relation to total tax revenue, it still sends an important signal that rich individuals also have obligations as taxpayers and are subject to auditing.

Taxing individuals’ wealth is important in increasing the progressivity of a tax system. For example, the excessive taxation of financial assets may not be advisable, as such assets can easily cross borders and represent an important source of investment finance, which is typically scarce in many African countries. An alternative could be to tax non-moveable assets, such as property. New technology (digital maps, mobile banking, etc.) has made it easier to identify property and develop electronic payments systems. For example, according to a World Bank paper External link, opens in new window., in Kigali revenues could increase tenfold through a 1 per cent value-based tax on property. This would also spread the tax burden more equally, since the current system is plagued with exemptions, often favouring the rich. Taxing property has the potential to become an important revenue source to finance public investment in African cities, as rapid urbanisation will continue to boost property prices, and hence revenue.

External link, opens in new window., in Kigali revenues could increase tenfold through a 1 per cent value-based tax on property. This would also spread the tax burden more equally, since the current system is plagued with exemptions, often favouring the rich. Taxing property has the potential to become an important revenue source to finance public investment in African cities, as rapid urbanisation will continue to boost property prices, and hence revenue.

Corporate taxation and combating the tax avoidance of big multinationals

Corporate profit tax rates in Africa vary from a low of 15 per cent (Mauritius) to a high of 35 per cent (Chad, Gabon and Sudan, among others), with a median rate of 30 per cent. But the amount that companies actually pay – their effective tax burden – differs significantly from the statutory rates. For example, in Zimbabwe, numerous exemptions reduce the statutory rate of 35 per cent to a de facto rate of less than 20 per cent. In other countries, however, the de facto profit tax rate is higher than the statutory rate, often due to the same (or similar) taxes being levied several times over at different government administrative levels. For example, a recently published global comparison study of corporate taxes External link, opens in new window. shows that in rich, high-tax countries – such as New Zealand, Norway and Sweden – around five taxes are paid by companies. Meanwhile, in several African countries (for example, Rwanda, South Africa and Tunisia) around 10 taxes are paid. In yet other countries – for example, Nigeria, Tanzania and Zimbabwe – the number can be upwards of 50. A plethora of taxes provides an incentive for formal businesses to become informal. This creates a situation in which some firms are taxed only partially, if at all, while others are fully captured in the tax net.

External link, opens in new window. shows that in rich, high-tax countries – such as New Zealand, Norway and Sweden – around five taxes are paid by companies. Meanwhile, in several African countries (for example, Rwanda, South Africa and Tunisia) around 10 taxes are paid. In yet other countries – for example, Nigeria, Tanzania and Zimbabwe – the number can be upwards of 50. A plethora of taxes provides an incentive for formal businesses to become informal. This creates a situation in which some firms are taxed only partially, if at all, while others are fully captured in the tax net.

Even if large firms are relatively few in number, the sheer size of a large firm’s operations implies that a significant share of corporate revenue comes from the largest firms, even if some avoid paying certain taxes by shifting their profits. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) recently struck a global deal to ensure that big multinational companies pay a minimum tax rate of 15 per cent. By reallocating some taxing rights to countries where real economic activity takes place, the deal will also make it harder for these companies to avoid taxation. The deal is part of the OECD’s drive to counteract corporate tax-planning strategies used by multinational companies to shift profits from higher-tax countries to lower-tax countries. Similar ideas on how to combat tax-base erosion and profit shifting are outlined in President Biden’s Made in America Tax Plan and have the potential to increase revenue from large global corporates. In absolute terms, the gains from such initiatives are likely to benefit rich countries most; but they will still be important to many African countries, as corporate taxes still form a large source of revenue.

Taxation, digitalisation and inclusiveness

The social and economic consequences of the Covid pandemic have been widely observed across the world, including in African countries. African governments that have invested in digital public goods have been better at scaling up their social assistance programmes to protect the poor during the pandemic; however, low revenue mobilisation can make it hard or impossible for governments to do this. Such expansion requires significant resources, and governments need to focus on broad-based taxes, such as income tax and VAT. One argument against removing VAT exemptions is that it could hurt the poor, since they spend a large proportion of their incomes on exempted products, such as food. A recent empirical analysis External link, opens in new window. of a broad set of countries, which takes into account informal consumption, finds that consumption taxes such as VAT are progressive and that exemptions have no redistributive impact. In addition, a study by the Institute for Fiscal Studies

External link, opens in new window. of a broad set of countries, which takes into account informal consumption, finds that consumption taxes such as VAT are progressive and that exemptions have no redistributive impact. In addition, a study by the Institute for Fiscal Studies External link, opens in new window. also shows that VAT exemptions are costly, with estimates ranging from a little under a quarter of VAT revenues in Ethiopia to around a third in Senegal and Zambia. Broadening the VAT base would generate significant revenue gains, which, combined with further investment in social protection programmes, could provide the basis – at least in part – of a sustainable welfare programme.

External link, opens in new window. also shows that VAT exemptions are costly, with estimates ranging from a little under a quarter of VAT revenues in Ethiopia to around a third in Senegal and Zambia. Broadening the VAT base would generate significant revenue gains, which, combined with further investment in social protection programmes, could provide the basis – at least in part – of a sustainable welfare programme.

While they are reluctant to remove VAT exemptions, governments have turned their attention to numerous ‘small’ taxes, particularly on services delivered by the digital and mobile communications industries. The appetite for short-term revenue gains – such as the excessive taxation of social media (e.g. in Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe) and the mobile communications industry – offers a good example of coercive government behaviour and policies that have a detrimental effect not only on building trust, but also on income equality and future tax revenue. For example, the empirical evidence from Kenya External link, opens in new window. suggests that that country’s excessive rates of tax on internet services, mobile phones (air time) and mobile financial transactions are having a negative impact on poor people’s livelihoods. The benefits of low-cost mobile banking technology (which has improved access to financial services, particularly in rural areas) have been significant. They include increased productivity among small farmers, opportunities for self-employment, and greater food security for poor households. Notably, the impacts are more pronounced in the case of female-headed households. Excessive taxation, however, jeopardizes such progress.

External link, opens in new window. suggests that that country’s excessive rates of tax on internet services, mobile phones (air time) and mobile financial transactions are having a negative impact on poor people’s livelihoods. The benefits of low-cost mobile banking technology (which has improved access to financial services, particularly in rural areas) have been significant. They include increased productivity among small farmers, opportunities for self-employment, and greater food security for poor households. Notably, the impacts are more pronounced in the case of female-headed households. Excessive taxation, however, jeopardizes such progress.

During the pandemic, ready access to both reliable internet and affordable data has become essential; but large swathes of the population of Africa cannot afford it. In some countries (Chad, Guinea, Zambia and Madagascar), taxation accounts for more than a third of the total cost of mobile internet. In seven countries (DRC, Malawi, Chad, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Niger and Madagascar) the level of taxation represents more than 5 per cent of monthly income for the poorest 40 per cent of the population. An inclusive development agenda should consider that mobile internet has significant positive externalities and so should attract a low rate of taxation – or even be subsidised. In sum, the revenue authorities should focus on large tax bases and taxes that generate a significant amount of revenue, and avoid taxes that distort future income opportunities, in particular among the poor.

Policy recommendations

While the heterogeneity of African countries, in terms of both their administrative structure and fiscal capacity, means that tax policy advice must be highly contextualised, there are a number of lessons to be learnt from past successes and mistakes. First, in order to transition towards larger tax bases, while simultaneously taking social protection into consideration, tax systems require reform. To achieve this, the following should be borne in mind:

- Improving revenue performance needs to focus on three large tax bases: income, consumption (VAT) and wealth. Focusing on a single tax base (such as wealth) or concentrating on illicit flows cannot in itself dramatically change a country’s fiscal position. The efficient use of all available tax bases can improve revenue performance significantly. However, governments should avoid the excessive taxation of new technologies that are important inputs into the transformation of society.

- A tax system needs to be easily understood. Despite years of reform, individuals in many African countries still have difficulty in understanding what taxes they should pay. Tax systems that are complicated or time-consuming are often enforced by weak institutions. Combined with a general lack of trust, this contributes to an environment in which the incentives to avoid paying taxes are accentuated.

- Many African states need to speed up the registration of taxpayers. Improving compliance requires collaboration between various government departments and financial institutions. Recent trends to speed up the use of digital platforms have provided important incentives for taxpayers to register.

- Increased collaboration on an equal footing – both globally and between individual African revenue authorities – can yield mutual benefits, particularly when it comes to tackling tax evasion among large (corporate and individual) taxpayers. There are also several domestic policy measures that could reduce tax avoidance: for example, removing a number of exemptions and making the tax system more uniform. Strengthening analytical capacity within government and the tax authority to handle large databases could have a significant impact on revenue.

NAI Policy Notes is a series of research-based briefs on relevant topics, intended for strategists, analysts and decision makers in foreign policy, aid and development. They aim to inform public debate and generate input into the sphere of policymaking. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute.

About the author

- Jörgen Levin, senior researcher at NAI, has many years of experience as researcher on inclusive growth, taxation, public spending, macroeconomics and sustainable development goals (SDG).

Further reading

The NAI policy notes series is based on academic research. For further reading on this topic, we recommend the following titles:

- Ross Warwick, Tom Harris, David Phillips, Maya Goldman, Jon Jellema, Gabriela Inchauste and Karolina Goraus-Tańska (2022). The redistributive power of cash transfers vs VAT exemptions: A multi-country study

External link, opens in new window.. World Development Volume 151, March 2022. Elsevier Ltd.

External link, opens in new window.. World Development Volume 151, March 2022. Elsevier Ltd. - Jörgen Levin (2021), Taxation for Inclusive Development

External link, opens in new window.. Current African Issues No 68. The Nordic Africa Institute.

External link, opens in new window.. Current African Issues No 68. The Nordic Africa Institute. - Mick Moore, Wilson Prichard, Odd-Helge Fjeldstad (2018). Taxing Africa: Coercion, reform and development

External link, opens in new window.. Zed Books, London.

External link, opens in new window.. Zed Books, London. - Njuguna Ndung’u (2019). Taxing mobile phone transactions in Africa: Lessons from Kenya

External link, opens in new window.. Policy Brief. Africa Growth Initiative. Brookings.

External link, opens in new window.. Policy Brief. Africa Growth Initiative. Brookings. - Pathways for Prosperity Commission (2019). The Digital Roadmap: How developing countries can get ahead

External link, opens in new window.. Final report of the Pathways for Prosperity Commission. Oxford, UK.

External link, opens in new window.. Final report of the Pathways for Prosperity Commission. Oxford, UK.

How to refer to this policy note:

Levin, Jörgen. (2022). After the pandemic - an opening for tax reforms: Post-Covid taxation challenges across Africa. (NAI Policy Notes, 2022:1). Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:nai:diva-2629 External link.

External link.