Towards an African feminist institutionalism for women’s political representation

Zimbabwe People First (ZIMPF) former leader and Vice President Joice Mujuru, next to Morgan Tsvangirai, former leader of Zimbabwe's main opposition during a march against what protesters say is themishandling of the the country's economy. Photo: Philimon Bulaway, Reuters.

A new book, Gendered Institutions and Women’s Political Representation in Africa calls for a focus on institutional barriers to women in politics – formal and informal – as an introduction of isolated formal gender equality reforms have provided mixed results. Despite this, African countries without quotas are still looking towards these reforms as the main model for promoting political empowerment. This policy note argues that these need to be combined with a regendering of institutions working against more women in politics and suggests steps towards an African feminist institutionalism for women in politics.

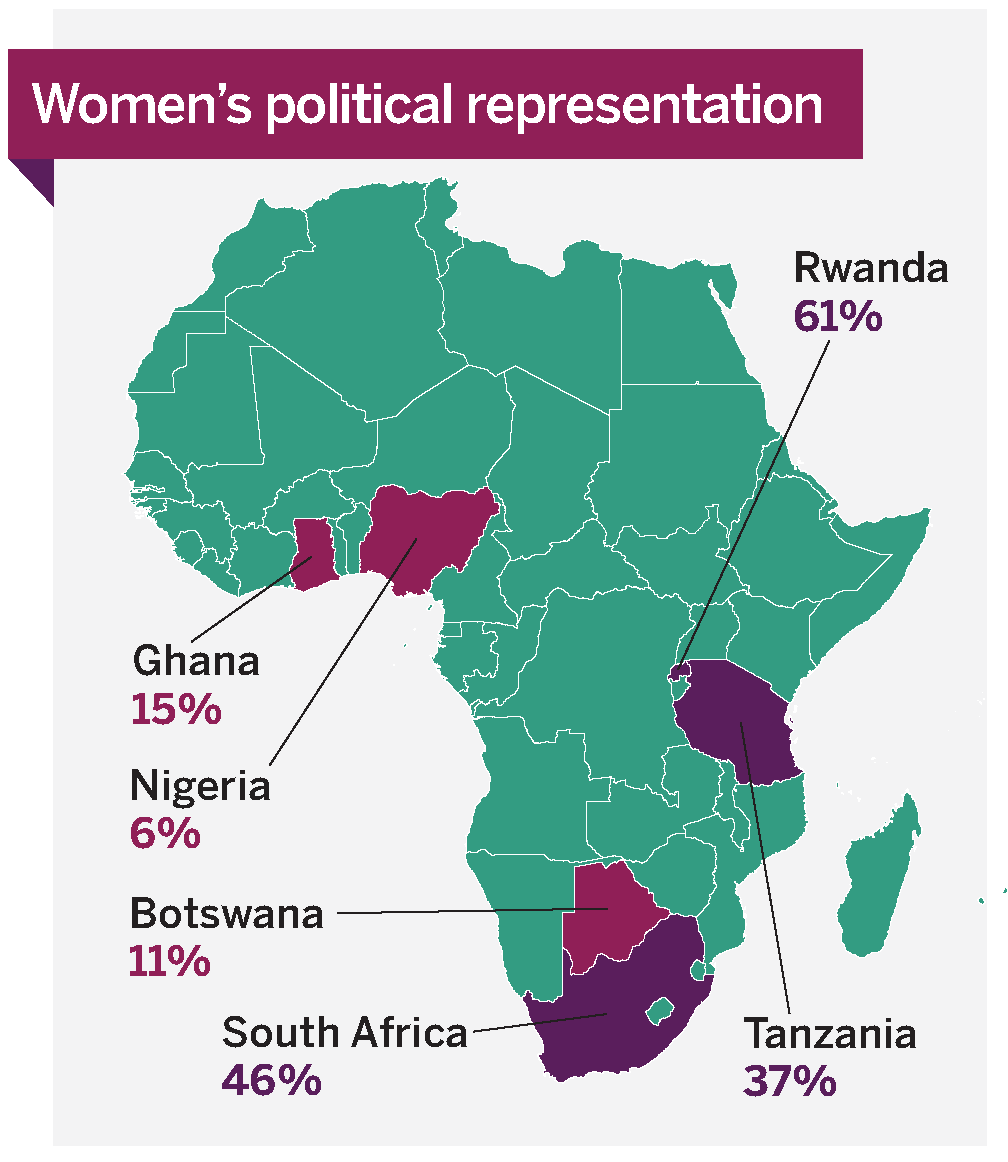

Development in women’s political representation has been uneven on the African continent. Rwanda ranks highest in the world in terms of numbers (descriptive representation), with a 61% representation of women in parliament, South Africa 46% and Tanzania 37%. Countries at the other end of the spectrum are Ghana with 15%, Botswana 11%, and Nigeria 6% (Global Gender Gap Report 2021 External link, opens in new window.). The book Gendered Institutions and Women’s Political Representation in Africa’ (2021)

External link, opens in new window.). The book Gendered Institutions and Women’s Political Representation in Africa’ (2021) External link, opens in new window. examines eight African country case studies (South Africa, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Malawi, Tanzania, Kenya, Nigeria and Ghana) and the role of institutions in explaining their uneven development. This policy note draws on the findings of the book. The importance of the topic of feminist leadership is emphasised by the choice of ‘Women in Public Life – Equal Participation in Decision-Making

External link, opens in new window. examines eight African country case studies (South Africa, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Malawi, Tanzania, Kenya, Nigeria and Ghana) and the role of institutions in explaining their uneven development. This policy note draws on the findings of the book. The importance of the topic of feminist leadership is emphasised by the choice of ‘Women in Public Life – Equal Participation in Decision-Making External link, opens in new window.’ as the topic for the UN Commission on the Status of Women 2021.

External link, opens in new window.’ as the topic for the UN Commission on the Status of Women 2021.

Institutions are both formal and informal, understood in a broad sense defined by Waylen External link, opens in new window. (2013) as ‘rules and procedures that structure society by constraining and enabling [an] actor’s behaviour’. Focus has often been at either micro-level on the framing of individual women’s needs framing or at macro-level on electoral systems. The first frames women candidates in a ‘deficit’ situation, whereas the latter places the widespread ‘first-past-the-post’ or ‘winner-takes-all’ system, which is not that open to newcomers in politics, as the sole explanation for a low representation of women in politics in a deterministic manner. In contrast, a focus at meso-level, on gendered formal and informal institutions, provides insights and opportunities for gender transformation.

External link, opens in new window. (2013) as ‘rules and procedures that structure society by constraining and enabling [an] actor’s behaviour’. Focus has often been at either micro-level on the framing of individual women’s needs framing or at macro-level on electoral systems. The first frames women candidates in a ‘deficit’ situation, whereas the latter places the widespread ‘first-past-the-post’ or ‘winner-takes-all’ system, which is not that open to newcomers in politics, as the sole explanation for a low representation of women in politics in a deterministic manner. In contrast, a focus at meso-level, on gendered formal and informal institutions, provides insights and opportunities for gender transformation.

Solutions need to move beyond the introduction of quotas

‘Success countries’ are characterised by formal gender equality reforms in the form of quotas introduced either in the aftermath of conflicts (for example, Rwanda in 2003 and South Africa in 1994) or as a part of broader constitutional reforms (Kenya in 2010 and Tanzania in 2005). However, the experiences of Kenya, Tanzania and South Africa demonstrate that institutional barriers to women in politics persist even beyond the introduction of quotas. In Kenya, the introduction of a quota in 2010 with a female representative in each county in Parliament has not led to substantial changes among the Maasai community. Only one woman member of parliament (MP) is in place, though women are entitled to 11 seats. Furthermore, women limit themselves to these special seats, which has not seriously challenged political patronage, with huge costs for women.

Tanzania and South Africa have introduced quotas in line with the 2008 SADC Protocol on Gender and Development External link, opens in new window., aiming for a 50-50 representation. In Tanzania, a 30% quota was adopted in 1985, but results have been mixed. On a negative note, the ruling party controls the allocation of special seats, opening the way for manipulation including sexual corruption and unquestioned loyalty towards the party versus a gender equality agenda. These seats are viewed as inferior and opponents are calling for their abolition, arguing that they should be temporary measures. On a more positive note, it has changed attitudes towards women politicians, led to the passing of gender equality legislation and improved interactions between men and women MPs.

External link, opens in new window., aiming for a 50-50 representation. In Tanzania, a 30% quota was adopted in 1985, but results have been mixed. On a negative note, the ruling party controls the allocation of special seats, opening the way for manipulation including sexual corruption and unquestioned loyalty towards the party versus a gender equality agenda. These seats are viewed as inferior and opponents are calling for their abolition, arguing that they should be temporary measures. On a more positive note, it has changed attitudes towards women politicians, led to the passing of gender equality legislation and improved interactions between men and women MPs.

In South Africa, a quota of 50% is in place, but in line with Tanzania women have become instrumental in upholding the ruling African National Congress (ANC) party. Some refer to the ANC’s ‘Women’s League’ syndrome, with its conservative focus on women as wives or mothers of the nation. In Zimbabwe, the introduction of a 30% quota led to accusations that the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) party was scoring cheap political points as a way to legimise the regime. However, the media presented it as ‘the fuzzy maths of SADC’. In turn, this was portrayed as ‘the fuzzy woman Vice President’, then Joice Mujuru. In Nigeria, the military regime introduced a quota in 1983 in the form of a directive stating that there should be one woman appointed as a member of the Executive Council in each state – a token representative serving to legitimise the regime.

The less successful countries in terms of the number of women in parliament are looking towards the introduction of quotas as the main solution. However, solutions need to move beyond an isolated focus on the introduction of formal gender equality reforms and tackle institutional barriers – formal as well as informal.

Maasai women in the Nerok county, Kenya. In the Maasai communitywomen are expected to show respect for men (enkanyit) and not demonstrate any opposition. Photo: Kandukuru Nagarjun.

Informal institutions are working against women in politics

Feminist institutionalism takes as its point of departure that institutions have gendered norms and rules and will therefore produce gendered outcomes. This can be the case for both formal and informal institutions; however, often, informal institutions work against greater numbers of women in politics and feminist leadership. These are characterised by being unwritten and created, communicated and enforced outside the formal sphere (ibid.) and work against or in parallel to formal institutions. Informal institutions often serve to maintain existing gender or power structures by preserving the status quo, but they can also support women’s political representation. They often work when formal institutions are weak or politics is characterised by informality and patronage networks.

Different informal institutions persist in African contexts where women are excluded from political office. In the Maasai community in Kenya, women are expected to show respect for men (enkanyit) and not demonstrate any opposition. A lack of enkanyit invites physical abuse domestically and public shaming or shunning. The first woman Maasai MP, Peris Tobiko, has been exposed to threats, alienation and curses from Maasai elders. In Ghana, a ‘politics of insults, ridicule and rumours’ excludes women from political office, including name-tagging (as prostitutes, witches or as having masculine traits), cartooning and innuendio about transactional sex in exchange for campaign donations. In Zimbabwe, the media stereotyped the former vice-president, Joice Mujuru, who was active in politics between 1980 and 2013, setting her up to fail. Using the prefix ‘Mai’ with her first name established connotations with wife- and motherhood at the expense of her professional record as a combatant and military officer during the liberation struggle and her ministerial positions during the regime of Robert Mugabe. Other constructs framed her as a ‘saint’ among political sinners or a ‘freak’ for showing anger like a man in a woman’s body.

In Malawi, local male political networks exclude some women candidates from the primary election. As the elections in 2014 and 2019 were characterised by informality, with formal rules transmitted orally, the process of selecting candidates left room for manoeuvre for a range of manipulations to promote male candidates. Women candidates were excluded from crucial information on times, dates and venues in the process and a male candidate was declared the winner, despite evidence to the contrary. Furthermore, the elections were characterised by electoral violence to ‘stir things up’ and introduce unknown candidates. In South Africa, the ANC has hijacked the process of making up the lists for candidacy (using a proportional closed list system) with a ‘zebra list’, alternating between male and female candidates. This has led to ‘slate politics’, where party loyalty and affiliation with particular factions has become the entry ticket for male political gatekeepers at the expense of professional credentials and commitment to a gender equality agenda.

Re-excavating the past – the role of historical women political icons

As institutions are gendered, they can also be re-gendered. Potentially, institutions can be transformed in a more gender-friendly direction through alliances between gender actors and influential political actors. Various strategies for regendering institutions can be identified in African contexts. One strategy is to ‘re-excavate’ the past, moving beyond the colonial to unveil the negative influence of colonisation and colonial institutions on women’s political representation, which vested power in local male authorities. Instead, the book suggests searching for alternative legitimising reference points in pre-colonial women political icons and institutional arrangements.

In Kenya, colonialism influenced Maasai communities and women’s political representation through indirect rule, as male political authority and economic control were reinforced by new bases of power and control over land for agriculture and cattle. This in turn relegated women to wifehood and motherhood, with limited powers for action. Similarly, British Victorian ideals expecting women to be subordinate to men, confined to the home with child-rearing and domestic chores, became influential in Nigeria during the colonial period. This, despite a pre-colonial past with Amazons and warrior queens. For example, Queen Amina (who reigned from 1576 to 1610) from the city of Zaire in Kaduna state protected the city from invasion, extended it beyond its boundaries and transformed it into a prominent commercial centre. Similarly, in the ancient Yoruba lands, the oba (king) ruled with the help of eight palace women under the Amazon Moremi of Ile-Ife.

In Tanzania, women’s struggle in the liberation movement, with Bibi Titi Mohammed as a forerunner, has been neglected. Bibi Titi Mohammed was a leader of the women’s section of Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) and mobilised women. Later, she became the only woman in the government of Julius Nyerere and the leader of the women’s organisation Umoja wa Wanawake. Her contributions to history could be revisited and serve as symbolic inspiration for current women MPs in Tanzania.

Nego-feminism as a tool for regendering institutions

Another strategy for reshaping patriarchal institutions is to introduce African feminisms. ‘Nego-feminism’ is understood as the ‘feminism of negotiation’ and ‘no ego’ feminism linked to African cultures of compromise and balance. Nnaemeka (2004) describes nego-feminism as an African feminism External link, opens in new window., which knows when, where and how to detonate ‘patriarchal landmines’, but also to go around them – a form of realism and pragmatism rooted in African contexts. The introduction of nego-feminism challenges which versions of feminism should form part of ‘the feminist’ and Western notions often implied in research on feminist institutionalism.

External link, opens in new window., which knows when, where and how to detonate ‘patriarchal landmines’, but also to go around them – a form of realism and pragmatism rooted in African contexts. The introduction of nego-feminism challenges which versions of feminism should form part of ‘the feminist’ and Western notions often implied in research on feminist institutionalism.

Gendered African realities that stimulate a search for alternative reference points in historical female political icons from pre-colonial times and liberation struggles also introduce new versions of institutionalism – a ‘symbolic feminist institutionalism’ – recognising the role of female political icons, with a focus on sites of commemoration. Examples are the statues of Bibi Titi Mohammed, a Muslim Swahili woman with limited education who mobilised women at her first political meeting in 1955, leading 400 women to join TANU; or Ghanaian Queen Mother Yaa Asantewaa from Ejisu, who organised 45,000 to fight against the siege of Kumasi. Symbols matter in acknowledging the work of prominent women in independence struggles and nation-building, which is equally important but has actively been rendered invisible. In 2015, the South African #RhodesMustFall movement also highlighted the role of symbols External link, opens in new window. in the rewriting of African history. Both of these rewritings of history are elements of a decolonisation process challenging patriarchal and white supremacy. The first attempts to highlight and increase the visibility of black African female political icons; and the latter to diminish or erase the role of white male colonisers such as Cecil Rhodes as the most significant in African history.

External link, opens in new window. in the rewriting of African history. Both of these rewritings of history are elements of a decolonisation process challenging patriarchal and white supremacy. The first attempts to highlight and increase the visibility of black African female political icons; and the latter to diminish or erase the role of white male colonisers such as Cecil Rhodes as the most significant in African history.

Negotiating with male political networks – establishing strategic alliances

Male political networks and patronage politics are often presented by gender researchers and practitioners as working against the presence of more women in political offices . Informal institutions are ‘sticky’ and work as mechanisms for exclusion. Bjarnegård (2013) indicates that the focus should be on men’s overrepresentation in politics External link, opens in new window. and what purposes the male political networks and patronage politics serve. Her term describing networks as ‘homosocial’ illustrates their one-gendered nature and the dependency of women politicians on these networks for access to instrumental (economic resources and contacts) resources.

External link, opens in new window. and what purposes the male political networks and patronage politics serve. Her term describing networks as ‘homosocial’ illustrates their one-gendered nature and the dependency of women politicians on these networks for access to instrumental (economic resources and contacts) resources.

However, women politicians are not just victims of broad undefined ‘male political networks and political patronage’. They also negotiate and strategically use these features to promote their own agendas. In South Africa, women are included in these networks if they are compliant and vest their loyalty in the ANC first and foremost, implying that is it not only a ‘male’ set-up. Even though the compliant South African women MPs have participated in undermining gains made in women’s empowerment and gender equality, they create room for manoeuvre for women’s numerical representation. In Ghana, women politicians form alliances with male political networks to ensure support for pro-women/gender equality initiatives if the women identify that the networks support them and their agendas. This can be illustrated with reference to the importance of motherhood, which is highly valued in Ghana. Thus, nego-feminism is also part of political tactical manoeuvring.

Alternative feminist institutional spaces

Candidate training can, if properly designed, provide alternative feminist institutional spaces. In Botswana, non-governmental organisation (NGO) Letsema came into being in 2013 with support from different external donors. The NGO illustrates the value of alternative feminist institutional spaces. Letsema means ‘the ploughing season’, but also refers to farmers’ local practice of working together as a team and taking turns to work on each other’s farms, indicating the need for sharing resources on farms, as well as in political life. The first lesson learnt from Letsema is that processes of political empowerment move beyond formal politics and are interlinked with processes of empowerment in other spheres (social and economic). Some women who attended training workshops managed to get into politics at community level and later used the skills they acquired – in networking, fundraising and media training – to embark on larger agricultural projects; they also mentored other women from different backgrounds in the community.

The second lesson from Letsema is that the focus should not just be on the individual woman, but on collective processes of empowerment. The training sessions are inspired by a feminist participatory action approach, combining singing, storytelling and the use of social media and professional expertise. Mutual mistrust between women from different political parties could be overcome through singing and storytelling, with a focus on common gendered experiences to establish ‘safe places’ for the women candidates. An added bonus of the training workshops were the female political networks built as the basis for further collective initiatives within and outside political life.

A third lesson from the work of Letsema is the need to focus on strategies for greater visibility of female candidates. Letsema has supported women in the use of social media, to make sure that the ‘herhistories’ of the candidates are being told. Furthermore, Letsema supported the production of a common poster for female candidates with the main message ‘Vote for a woman’ in the 2019 election.

While there are valuable lessons to learn from the Letsema experience, training workshops are not a universal solution or an item to tick off donors’ to-do list, leaving political decision makers and political parties off the hook to address women’s political (under)representation or rather men’s overrepresentation. Therefore, it is important to tackle institutional barriers through a variety of initiatives and target groups.

Recommendations

- Increase the visibility of historic black female political icons for the strategic use of claims-making and legitimacy for entry into political spaces and include them as reference points in women candidates’ training.

- Candidate training for political office should address institutional barriers and provide feminist ‘safe spaces’, with a focus on collective political empowerment processes. This could help forge cross-party alliances, facilitate empowerment processes in other spheres (economic and social) and increase the visibility of women candidates collectively.

- The introduction of quotas should be monitored closely. Clear guidelines and rules for control of the process should be developed, including criteria for selection; for example, focusing on the intersecting categories of class, age, sexuality, ethnicity, etc.

- Political parties should pay more attention to institutional arrangements and how informal institutions often exclude women from political offices and uncover the hidden life of these institutions; for example, through processes of consultation with cross-party women’s caucuses or women’s organisers in the party leadership.

- Political parties should mainstream gender and diversity in terms of appointments to party leadership and committee positions.

- Political parties should develop guidelines for supporting women candidates. This could include potential financial support – for example, a fund for women candidates – and immediate responses to different forms of violence against women in politics, online and offline.

Research on this topic

Diana Højlund Madsen (2021): Gendered Institutions and Women's Political Representation in Africa External link, opens in new window., Africa Now Series, ZED Books, Bloomsbury.

External link, opens in new window., Africa Now Series, ZED Books, Bloomsbury.

Diana Højlund Madsen (2020): Gender, Politics and Transformation in Ghana: The role of critical actors External link, opens in new window., in E. Fallaci (ed.), Women: Opportunities and Challenges, New York, Nova Science Publishers.

External link, opens in new window., in E. Fallaci (ed.), Women: Opportunities and Challenges, New York, Nova Science Publishers.

Diana Højlund Madsen, Kwesi Aning, Kajsa Adu Hallberg (2020): A Step Forward but no Guarantee of Gender Friendly Policies – Female Candidates Spark Hope in the 2020 Ghana Elections External link, opens in new window., Policy Note, Nordic Africa Institute.

External link, opens in new window., Policy Note, Nordic Africa Institute.

Diana Højlund Madsen (2019): Gender, Power and Institutional Change – The Role of Formal and Informal Institutions in Promoting Women’s Political Representation in Ghana External link, opens in new window., Journal of Asian and African Studies, vol. 54, issue 1, pp. 70–87.

External link, opens in new window., Journal of Asian and African Studies, vol. 54, issue 1, pp. 70–87.

Diana Højlund Madsen (2019): Women’s Political Representation and Affirmative Action in Ghana External link, opens in new window., Policy Note, Nordic Africa Institute.

External link, opens in new window., Policy Note, Nordic Africa Institute.