Democratic backsliding in Côte d’Ivoire - Legislative elections tighten Ouattara’s grip on power

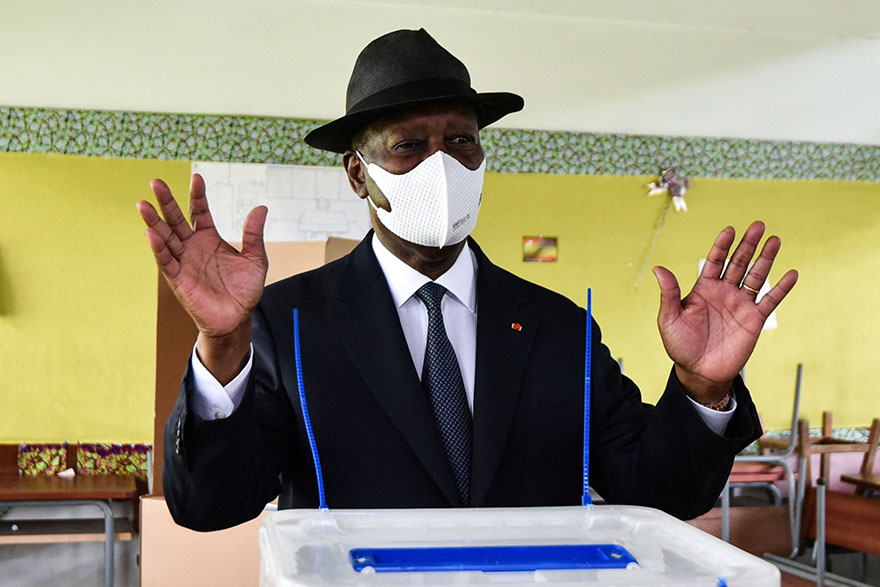

President Alassane Ouattara casts his ballot during Côte d'Ivoire's legislatives election on March 6, 2021. Photo by SIA KAMBOU / AFP.

The ruling RHDP’s victory in legislative elections in March 2021 has tightened incumbent President Alassane Ouattara’s grip on political power in Côte d’Ivoire. Though Ouattara has taken a conciliatory stance towards the opposition since his re-election, his control of political institutions, low voter turnout, electoral violence and the president’s international status heighten the risk of further democratic backsliding in Côte d’Ivoire.

Policy note by Jesper Bjarnesen, senior researcher at NAI and Sebastian van Baalen External link, opens in new window., researcher at the Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University.

External link, opens in new window., researcher at the Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University.

Download this Policy note as PDF. External link, opens in new window.

External link, opens in new window.

What’s new?

Côte d’Ivoire held legislative elections on 6 March 2021, four months after a violent presidential election that cost the lives of at least 87 people. The results, which were announced by the Independent Electoral Commission (CEI), indicate that the ruling Rally of Houphouëtists for Democracy and Peace (RHDP) won the majority of parliamentary seats, but the opposition has cried foul.

Why is it important?

Côte d’Ivoire is one of the most politically and economically important countries in West Africa but its elections have often been marred by violence. At least 3,000 people were killed during the 2010–11 electoral crisis, which ended the period of civil war that had been running since 2002. The country is home to a large migrant population from neighbouring Guinea, Mali, and Burkina Faso, and located in a subregion plagued by political instability. Côte d’Ivoire is also an important ally in the regional fight against armed jihadist groups across the Sahel. Thus, democratic backsliding in Côte d’Ivoire could have serious repercussions for West Africa as a whole.

What should be done and by whom?

External actors, most notably ECOWAS, the AU, UN and EU, should engage in dialogue with the government to counteract further moves towards lessening democratic freedoms in Côte d’Ivoire. These actors should also continue to promote the strengthening of democratic institutions, especially the Independent Electoral Commission. Looking ahead, it is essential that both domestic and international actors help establish a new political generation that can consolidate democracy by putting political programmes before personal loyalties.

Set against a backdrop of a violent election period in October 2020 that secured President Alassane Ouattara an unconstitutional third term in office, Ivorians once again headed to the polls on 6 March 2021 to elect a new National Assembly. A total of 255 parliamentary seats were contested in a vote that represented the opposition’s last chance for the foreseeable future to rein in Ouattara’s tightening grip on political power.

The opposition, led by the Democratic Party of Côte d'Ivoire (PDCI) and Ivorian Popular Front (FPI), consolidated a new coalition, which was born out of the former rivals’ common cause in objecting to Ouattara’s third term bid. However, the most important development was that the opposition decided to take part in the elections at all, having boycotted the presidential election. This meant that the legislative elections were the first time since 2010 that all three major political parties in Côte d’Ivoire had actively participated in an election.

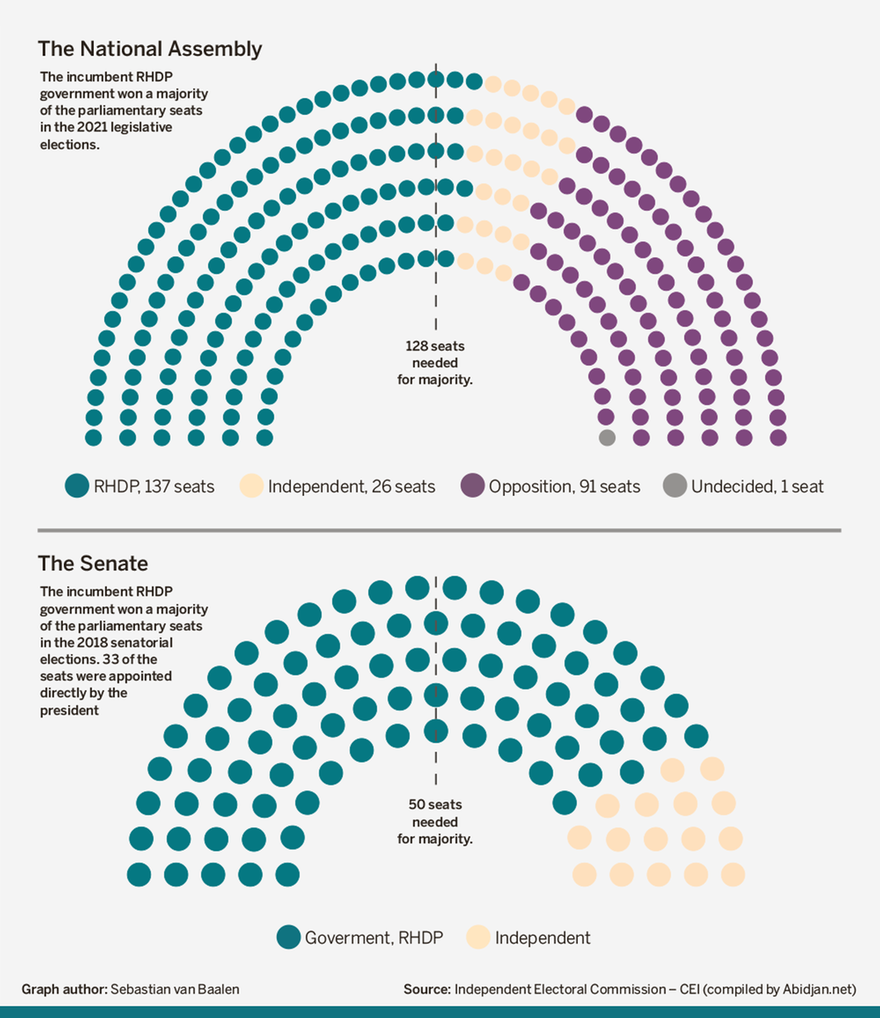

The elections brought another landslide victory for Ouattara, who won the presidential election with 95% of the popular vote only four months ago, consolidating his party’s dominance in parliament. The Rally of Houphouëtists for Democracy and Peace (RHDP) won 137 seats, safely above the 128 seats needed to dominate the National Assembly. Opposition parties won 91 seats, while independent candidates won the remaining 26 seats. This means that the RHDP retains control of the Presidency, National Assembly and Senate. However, the ruling party’s success in the legislative elections is just one of several signs of impending democratic decline in Côte d’Ivoire.

Personalities, not institutions, dictate democratic rules

In the face of sustained domestic criticism of his third term bid and lack of investment in genuine reconciliation after the end of the 2002–11 civil war, Ouattara made several conciliatory moves before the polls; for instance, releasing opposition leaders from jail, opening up dialogue with the opposition and broadening participation in the Independent Electoral Commission (CEI). These moves contributed to de-escalating serious tensions and violence that had marred the presidential election.

Alassane Ouattara (RHDP)

Ouattara’s lifting of restrictions on the opposition’s ability to participate in the legislative elections was a positive development. However, it was too little, too late. The arrests of opposition leaders and clampdown on protests that have occurred since the presidential election have hampered the opposition’s capacity to contest the legislative polls equitably. Furthermore, the Ouattara administration has passed several institutional reforms in the past five years that make for an uneven political playing field. The creation of the Senate in 2016, in particular, has centred power in the hands of the incumbent president. Finally, Ouattara’s government continues to exercise undue influence over other political institutions such as the judiciary and the Independent Electoral Commission.

Henri Konan Bedié (PDCI)

Given that the RHDP have retained the majority of the seats in the National Assembly, there are few constitutional ways for the opposition to hold the president or his government accountable. With such a tight grip on the country’s political institutions, respect for democratic principles becomes a matter of the president’s personal preference, rather than institutional checks and balances. Even within the ruling party, the untimely death in the past year of two of Ouattara’s prime ministers and closest allies, Amadou Gon Coulibaly and Hamed Bakayoko, may serve to concentrate power around the president even further.

This personalisation of the political process not only polarises the electorate, but also encourages the continuation of the destructive and personality-centred competition between Ouattara and his two ageing rivals, former presidents Henri Konan Bedié (PDCI) and Laurent Gbagbo (FPI).

Low voter turnout undermines democratic legitimacy

The participation of the PDCI and FPI in the election constitutes an important step towards a return to a more genuinely democratic political contest. The impending return of Gbagbo from exile in Belgium, from where he mobilised his supporters, seems to be another necessary yet potentially destabilising step towards de-escalation and de-polarisation of the Ivorian electorate, which has remained fundamentally divided since the civil war.

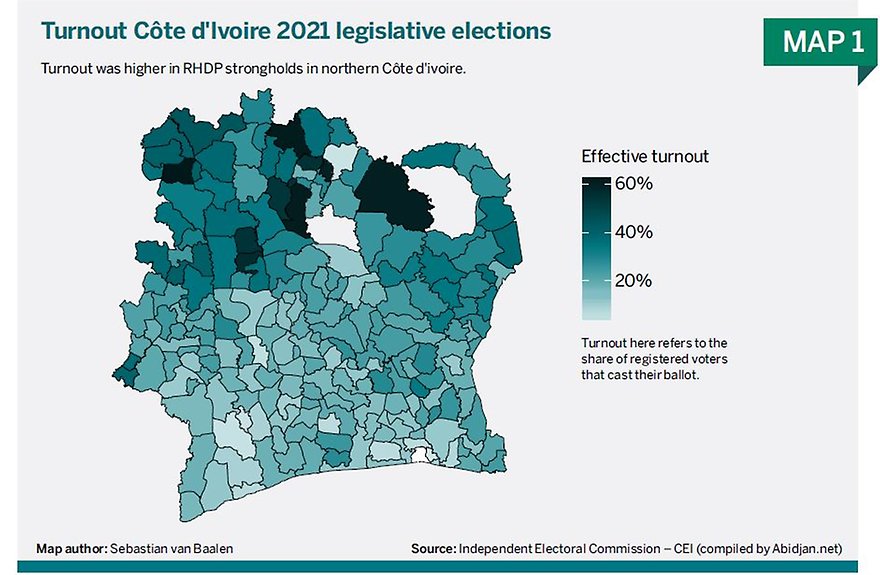

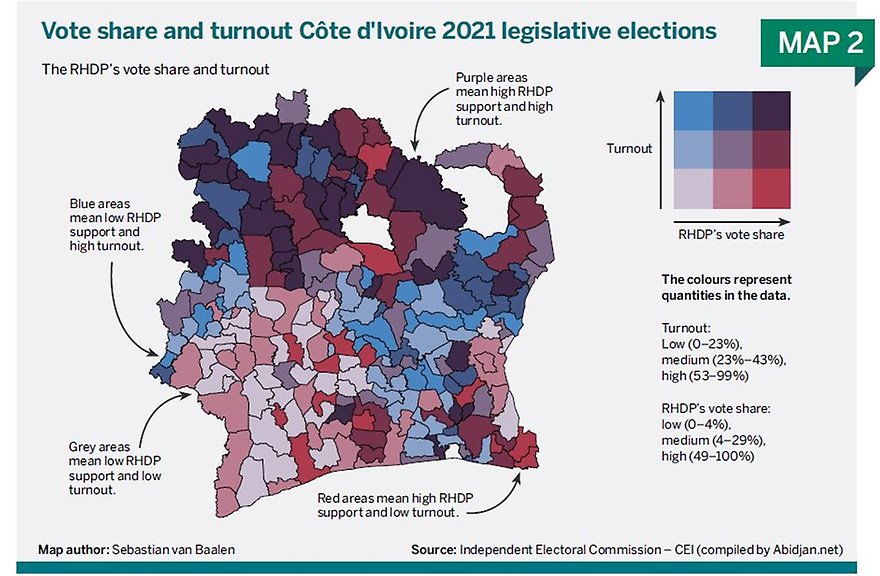

However, the opposition’s participation should be viewed in light of sustained voter abstention in opposition strongholds. Figures released by the Independent Electoral Commission show that turnout stood at 39%; a small increase from 34% in the 2016 legislative elections and considerably lower than the 54% turnout in the 2020 presidential election. Turnout in the 2021 legislative polls was less than half of the turnout in the 2010 presidential election, Côte d’Ivoire’s most recent truly competitive election. Moreover, turnout was far lower in opposition strongholds in the southwest and southeast, where the PDCI and FPI called an election boycott during the 2020 presidential poll, than in RHDP strongholds in the north (see map 1).

The low turnout in the 2021 legislative elections suggests that a large share of the electorate still perceive the electoral process as unimportant, illegitimate or outright dangerous. Thus, voter abstention continues to be a serious limitation on Côte d’Ivoire’s democratic legitimacy. These problems are evident from map 2 below, which shows that turnout was generally lower in opposition strongholds in the south than in RHDP strongholds in the north. The opposition’s boycott of the 2020 presidential election also weakened its ability to contest the legislative elections. Many opposition voters never registered. This meant that the opposition lost the elections well before election day External link, opens in new window..

External link, opens in new window..

Violent elections continue to undermine democracy

Considering that Côte d’Ivoire has suffered from a highly polarised political landscape for decades, and still faces serious reconciliation challenges in the aftermath of the civil war, the 2021 legislative elections were remarkably calm. Few violent incidents were reported before, on or after election day. This relatively calm environment is particularly noteworthy considering the involvement of Gbagbo, who has been a polarising figure in Ivorian politics since the 1990s.

Nonetheless, electoral violence continues to be a recurring cause of concern in Côte d’Ivoire. It has marred every important presidential election since the introduction of multiparty democracy in 1990. Many remember the 2010–11 electoral crisis, during which at least 3,000 people were killed. Violence also occurred during the two most recent elections, the 2018 municipal and 2020 presidential elections, albeit at lower levels. Human Rights Watch reports External link, opens in new window. that at least 87 people were killed around the presidential election. UNHCR estimated

External link, opens in new window. that at least 87 people were killed around the presidential election. UNHCR estimated External link, opens in new window. in late November 2020 that more than 17,000 Ivorians had fled the country due to fear of political violence. Such violence continues to impair the legitimacy of democratic elections in the country. Election observers noted

External link, opens in new window. in late November 2020 that more than 17,000 Ivorians had fled the country due to fear of political violence. Such violence continues to impair the legitimacy of democratic elections in the country. Election observers noted External link, opens in new window. serious obstruction of the electoral process in the presidential election, concluding that “the overall context and process of the polls did not allow for a genuinely competitive election”.

External link, opens in new window. serious obstruction of the electoral process in the presidential election, concluding that “the overall context and process of the polls did not allow for a genuinely competitive election”.

Ouattara’s legacy is still in the balance

So far, Alassane Ouattara’s political legacy has been a mixed bag. On the one hand, he has presided over one of the fastest-growing economies in the world, with an average annual growth rate of 8% since 2012. Even with the global Covid-19 pandemic, Côte d’Ivoire avoided recession in 2020. The country’s economy remains dangerously dependent on cocoa exports, but Ouattara has taken steps towards diversification. He has also shown the way when it comes to rehabilitating the country’s decaying infrastructure, such as the improvement of major roads and the expansion of the Port of Abidjan.

On the other hand, economic growth has yet to benefit most Ivorians. Income inequality and poverty have not decreased markedly over the past decade and infrastructure development projects are centred on the economic capital Abidjan. While Ouattara’s economic merits are often praised, his political legacy is more controversial. His presidency has been marked by continuous boycotts by one or several opposition parties. And he has repeatedly tinkered with the Constitution in ways that have strengthened his political hand at the expense of his competitors, most recently by pushing through amendments that allowed him to argue for his right to stand for an unconstitutional third term.

Many of his main challengers, including Gbagbo and former leader of the Forces Nouvelles and aspiring politician Guillaume Soro, are in exile. After the 2020 presidential election, prominent opposition leaders, including the leaders of the two foremost opposition parties Bédié and Pascal Affi N’Guessan (FPI), were arrested, harassed or placed under house arrest External link, opens in new window.. Not all these actions may have been intended to undermine democratic accountability, but the effect has nonetheless been to weaken democratic institutions.

External link, opens in new window.. Not all these actions may have been intended to undermine democratic accountability, but the effect has nonetheless been to weaken democratic institutions.

Ouattara retains international support, despite his undemocratic conduct

The negative democratic consequences of Ouattara’s political strategy have not damaged his international reputation in any serious sense. While the French government expressed concern over the violence around the 2020 presidential election, there were no immediate repercussions for Ouattara. International actors, and the French government in particular, remain committed to stability in West Africa over true democratic norms. In all likelihood, they would prefer to continue working with the technocratic and business-friendly Ouattara government than his populist and polarising competitors.

Two additional developments strengthen Ouattara’s position even further.

First, the French government is looking to reduce its involvement External link, opens in new window. in counterinsurgency operations across the Sahel, especially in violence-ridden Mali. Meanwhile, to stem further regionalisation of the Sahelian security crisis, Côte d’Ivoire has intensified anti-terror operations along its unstable border with Burkina Faso, where in June 2020 14 Ivorian soldiers were killed

External link, opens in new window. in counterinsurgency operations across the Sahel, especially in violence-ridden Mali. Meanwhile, to stem further regionalisation of the Sahelian security crisis, Côte d’Ivoire has intensified anti-terror operations along its unstable border with Burkina Faso, where in June 2020 14 Ivorian soldiers were killed External link, opens in new window.. The country has contributed 811 soldiers to the UN's MINUSMA peacekeeping mission in Mali

External link, opens in new window.. The country has contributed 811 soldiers to the UN's MINUSMA peacekeeping mission in Mali External link, opens in new window., a figure that is set to increase

External link, opens in new window., a figure that is set to increase External link, opens in new window.. The partial French withdrawal from the Sahel enables Ouattara to position himself as a key ally in the war on terror in the subregion and deflect international criticism, while simultaneously moving parts of the oversized and troublesome army

External link, opens in new window.. The partial French withdrawal from the Sahel enables Ouattara to position himself as a key ally in the war on terror in the subregion and deflect international criticism, while simultaneously moving parts of the oversized and troublesome army External link, opens in new window. out of the country.

External link, opens in new window. out of the country.

Second, democracy in West Africa is in decline. Mass protests have taken place in Senegal External link, opens in new window. over the arrest of opposition leader Ousmane Sonko, and President Macky Sall has responded with harsh repression. In otherwise relatively stable Ghana, several incidents of violence occurred around the presidential election in December 2020, in which incumbent President Nana Akufo-Addo held onto power. And in Guinea, incumbent President Alpha Condé recently defied a third term limit and was re-elected amid violent protests. These embattled presidents are unlikely to use ECOWAS as a forum to challenge Ouattara’s tightening grip on power.

External link, opens in new window. over the arrest of opposition leader Ousmane Sonko, and President Macky Sall has responded with harsh repression. In otherwise relatively stable Ghana, several incidents of violence occurred around the presidential election in December 2020, in which incumbent President Nana Akufo-Addo held onto power. And in Guinea, incumbent President Alpha Condé recently defied a third term limit and was re-elected amid violent protests. These embattled presidents are unlikely to use ECOWAS as a forum to challenge Ouattara’s tightening grip on power.

What next?

While the Ouattara government has presided over considerable democratic backsliding in Côte d’Ivoire in recent years, the country’s future stability depends on the moderation of all its main political actors, as well as on concerted diplomatic engagement by the international community. External actors, most notably ECOWAS, the AU, UN and EU, should engage in dialogue with the government to counteract further moves towards lessening democratic freedoms in the country. These actors should also continue to promote the strengthening of democratic institutions, especially the Independent Electoral Commission.

Looking ahead, it is essential that both domestic and international actors work towards reducing the dominance of Côte d’Ivoire’s ageing trio – Ouattara, Bédié and Gbagbo – and pave the way for a new political generation to consolidate democracy by putting political programmes before personal loyalties.

The elections brought another landslide victory to Ouattara which means that the RHDP retains control of the presidency, the National Assembly, and the Senate. With such a tight grip on the country’s political institutions, respect for democratic principles becomes a matter of the president’s personal preference, rather than of institutional checks and balances. Click for larger image.

NAI Policy Notes is a series of research-based briefs on relevant topics, intended for strategists, analysts and decision makers in foreign policy, aid and development. They aim to inform public debate and generate input into the sphere of policymaking. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute.