Redefining the social contract in Africa

Across a continent where large sections of the population feel

disconnected from meaningful citizenship, there is an urgent

need to redefine and strengthen the social contract. This was at

the core of a virtual public discussion hosted by the Nordic Africa Institute and Hanaholmen Swedish-Finnish Cultural Centre.

This policy note is also available as a downloadable pdf External link. or as a digital booklet

External link. or as a digital booklet External link, opens in new window..

External link, opens in new window..

The high-level seminar with thought leaders, scholars and policymakers from Africa and Europe discussed the changing character of the social contract in Africa, encompassing its role in social transformation. In addition, panellists considered how the Nordic countries could support African perspectives in the forthcoming negotiations of the African Union-European Union (AUEU) partnership.

Therése Sjömander Magnusson, the director of NAI, moderated and kicked off the digital event: “We know development is more than economic growth. In order to meet the challenges we have ahead it is fundamental that societies are built on trust and have agreements on rights and obligations. With this in mind, we want to put the role of establishing and investing in a strong social contract at the centre of this discussion”.

Hanna Serwaa Tetteh

In low-income countries, the social contract is limited because people have fewer expectations, while politicians have fewer resources to distribute. That is why a one size fits all approach will never work in Africa.

Kwesi Aning

“Political leaders create false expectations in their bid to win power. They know themselves they cannot deliver on election promises.”

Albeit a wide concept, the panelists agreed upon a number of features that constitute a social contract, such as rule of law, fairness, transparency, human rights and others. Adebayo Olukoshi, director of International IDEA in Africa and West Asia, added that it is in its predictability — people knowing what to expect from their governments — that a social contract is useful for citizens. However, according to Kwesi Aning, head of research at the Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre in Ghana, institutional capacity is low and resources are limited.

“Political leaders create false expectations in their bid to win power. They know themselves they cannot deliver on election promises”, he warned. Hanna Tetteh, the special representative of the UN secretary-general to the AU, pointed out the need to understand the African context. For instance, low-income African countries are facing completely different challenges to middle-income ones.

“Middle-income countries have resources, and the people expect that governments will deliver services. In low-income countries, the social contract is limited because people have fewer expectations while politicians have fewer resources to distribute. That is why a one size fits all approach will never work in Africa”, Tetteh explained.

The director of the European Think Tanks Group, Geert Laporte, stressed the elements of universality in a social contract. “I think it is essential for any type of cohesion in any type of society. At the same time, it is a living type of relationship that is evolving, which must be taken into account”.

What is needed, then, to deepen the social contract in Africa, Therése Sjömander Magnusson asked. Some panellists underlined that expectations from the citizenry cannot be met because of the fragility of state institutions.

Geert Laporte

It takes two to tango and the EU are still collaborating with the most corrupt leaders on the continent, perhaps out of fear of being sidelined by China.

Eleanor Fisher

Stakeholders are often excluded from the discussion. Such conversation should not only be between states, but also include plural voices from different corners of civil society.

Regional and sub-regional organisations on the continent have a lot of knowledge to share with state institutions, Hanna Tetteh pointed out. In addition, she underlined her hope that the new AU-EU partnership will not focus solely on the EU’s current priority on migration. It should rather look at issues relevant to the African continent, such as sustainable growth, green transition and digital transformation, but also peace and democratisation.

“Because we see a deterioration in the quality of governance – and governance is key to deliver on the development agenda. In addition, the economy is crucial for building a social contract, but the pandemic has had a huge impact, with dropping commodity prices and reduced returns from the service sector. The debt suspension service has helped, but more financial help is necessary”, Tetteh observed.

The COVID-19 crisis could make it even more difficult for states to deliver services to citizens. According to Jakkie Cilliers, head of African Futures & Innovation at the Institute for Security Studies (ISS), millions of Africans are at risk of falling into extreme poverty. On a more positive note, he mentioned the agreement on intercontinental free trade that could provide opportunities for leapfrogging to greater prosperity. Another important discussion, according to Cilliers, is what development routes African countries will take.

“In Ethiopia and Rwanda, social contracts stem from deep national traumas and both countries have taken development-oriented pathways not based on democracy. In history, development has always preceded democratisation. The Nordic countries perhaps can show us a different way, because we don’t want to go in the same direction as China”, Cilliers remarked.

A Ugandan woman is angry with her local council chair, whom she accuses of diverting money intended for health care. Photo: Frederic Noy/Panos Pictures.

According to both Eleanor Fisher, head of research at NAI, and Torbjörn Pettersson, former Swedish ambassador to the AU, the Nordics can contribute in areas where the social contract is particularly strong in their countries. For instance, welfare, democracy, gender equality and people´s high level of trust in governmental authorities, underpinned by low levels of corruption in public institutions. “But let’s not forget, there was no social contract in Sweden from the beginning. It had to be negotiated and moulded together over time to become strong”, Pettersson pointed out.

Just because something works in one place does not mean it will work in Africa. We must come to the negotiating table with our own knowledge, and with the power to reject what we know doesn’t work for us.

Several panellists stressed that zero-sum politics, 'where the winner takes all', is still all too common on the African continent and needs replacing with the will to mobilise societies to move forward. “Election losers are left out completely, which often leads to violence and undermines political will. We must enable political losers with the chance to fight another day”, Adebayo Olukoshi said. “At the same time there seems to be less space for leaders’ long-term thinking and policy making on the continent”, he added.

Jakkie Cilliers

In Ethiopia and Rwanda, social contracts stem from deep national traumas and both countries have taken development-oriented pathways not based on democracy. In history, development has always preceded democratisation. The Nordic countries perhaps can show us a different way, because we don’t want to go in the same direction as China.

Adebayo Olukoshi

Election losers are left out completely, which often leads to violence and undermines political will. We must enable political losers with the chance to fight another day. At the same time, there seems to be less space for leaders’ longterm thinking and policymaking on the continent.

Too often, ideas and experiences are imported from the global North to Africa as whole packages. Development cooperation is important, but we must not surrender completely, Olukoshi stated. “No region has a monopoly on answers and no region has a monopoly on problems. Just because something works in one place does not mean it will work in Africa. We must come to the negotiating table with our own knowledge, and with the power to reject what we know doesn’t work for us. There must be a limit on the culture of selling solutions”.

Geert Laporte agreed that donor and partner countries should not sell ready solutions that assume a certain type of social contract in Africa. However, that does not mean that experiences in the Nordics are not valuable, but rather that this calls for partnerships beyond a donor and recipient aid logic. “We must also understand there are vested interests at play, not only by African leaders but also by European leaders. It takes two to tango and the EU are still collaborating with the most corrupt leaders on the continent, perhaps out of fear of being sidelined by China”.

Laporte and Olukoshi together stressed that an active citizenship is the way forward, but unfortunately, donor agencies are only reaching a fraction of all civil society actors. Increased support, said Olukoshi, could give citizens a watchdog role over society similar to that in the Nordics. Laporte stressed that it is about leading by example, and there the Nordic countries have a role to play. “Because they don’t show the same double standards as many other donors. However, I also think Nordic countries should invest more in the EU than they currently do. It seems they are more interested in working globally or with the UN”.

Sinikka Antila

Building strong institutions is difficult, however, and we have been trying for a long time. First, we sent out experts, and then we tried projects and later budget support. I want to believe there is a willingness to overcome the bottlenecks, and I strongly believe we need to strengthen multilateral action between the EU and Africa.

Torbjörn Pettersson

But let's not forget, there was no social contract in Sweden from the beginning. It had to be negotiated and moulded together over time to become strong.

Torbjörn Pettersson thinks it is important that the EU considers the AU as the primary institution to engage in partnership, and thus avoid having many smaller bilateral agreements. “We also need to look beyond transactional agreements. We need to focus on global problems like climate change, the youth bulge, and that identity politics are taking over. If the focus is on economics, the donor-recipient model will prevail”, Pettersson said.

Sinikka Antila, the EU ambassador to Namibia, highlighted that EU and AU have more or less the same policies. But when it comes to implementation, there are many more bottlenecks on the African continent. “Weak institutions are an impediment to implementation of good policies. Building strong institutions is difficult, however, and we have been trying for a long time. First, we sent out experts, and then we tried projects and later budget support. I want to believe there is a willingness to overcome the bottlenecks, and I strongly believe we need to strengthen multilateral action between the EU and Africa”, Antila said.

Stakeholders are often excluded from the discussion, Eleanor Fisher remarked. Such a conversation should not only be between states, but also include plural voices from different corners of civil society. This brings issues of African agency to the fore and the need to include the voices of young people, women and those who are typically excluded. “However, it is not easy to ensure that people are in the dialogue”, Fisher observed. African agency was something several panelist spoke about. Moderator Therése Sjömander Magnusson defined it in this context as to have a voice and the ability to act, and to have influence on social transformation.

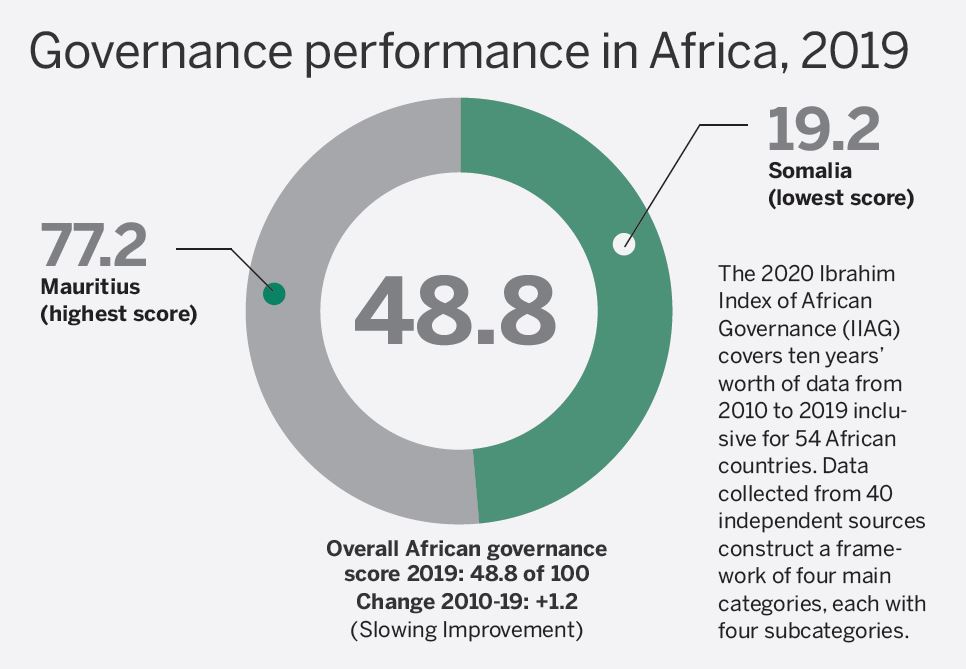

Governance performance in Africa. Visit iiag.online to explore and compare all IIAG data.

For Amanda Hammar, President of the European African Studies Association, it is important to discuss who has a say and where. “There are two domains of agency; the engagement with the outside – like partnerships with the Nordics or EU, and domestic engagement. But who is invited in, and by whom, to these engagements? This is an important dynamic, as well as the act of agency because there is plenty of room for citizens in various compositions to invent the spaces and make these come to the fore”.

Amanda Hammar

There are two domains of agency; the engagement with the outside – like partnerships with the Nordics or EU, and domestic engagement. But who is invited in, and by whom, to these engagements?

In this respect, the panel reinforced the view that African leaders need to move beyond rhetoric and show sincere willingness to address social divides and inequalities on the continent. “But also citizens must take an active role and responsibility. Several panellists emphasised the term ‘active citizenship’ in order to nurture the social contract. Here, the Nordic countries could have a role to play”, Sjömander Magnusson said.

According to Hanna Tetteh the problem is not only about imported models or lack of agency. It is also that values, ethics and integrity are universal, but not insisted on in the African context. “There are different standards in different countries. We need to insist on good governance principles and leaders must be held accountable by the institutions”, Tetteh underlined.

A young couple officially registers their marriage at a town hall in Burundi. Photo: Chris de Bode/Panos.

Therése Sjömander Magnusson, emphasised that one key message brought to the fore by all the panellists is the need to understand the underlying mechanisms that result in social cohesion in different societies. The social contract in and between African countries looks very different from what ties a society together in, for example, the Nordic region. Still, according to the panellists there is a genuine interest from African leaders to learn from outside the region and here the Nordic countries can lead by example. Therefore, an important question raised at the roundtable was how to co create a conversation to generate transformation towards an inclusive and just society.

Therése Sjömander Magnusson

In order to meet the challenges we have ahead it is fundamental that societies are built on trust and have agreements on rights and obligations. With this in mind, we want to put the importance of establishing and investing in a strong social contract at the centre of this discussion.

Gunvor Kronman

Young voices must be included in the AU-EU dialogue. We have to find ways for letting them be heard. Also during the Covid-19 crisis we see very clearly how girls’ rights and gender equality have taken big steps backwards. This we must address.

“One suggestion is to acknowledge that we have joint and complex problems that we need to address, but that the solutions have to be different, and this is where African perspectives, knowledge and agency are absolutely fundamental”, Sjömander Magnusson said.

It is easy to say that partnerships must be on equal terms, the panellists agreed, but yet so hard to achieve. “One way could be to discuss global challenges that we are all facing, defined in the Agenda 2030, because only through ‘togetherness’ will we enable social transformation”, Sjömander Magnusson concluded.

The director of the Hanaholmen Swedish-Finnish Cultural Centre, Gunvor Kronman, concluded the event by pointing to the need for broader social inclusion. While Europe has an ageing population, 75 percent of Africans are under 35 years old. “Young voices must be included in the AU-EU dialogue. We have to find ways for letting them be heard. Also, during the Covid-19 crisis we see very clearly how girls’ rights and gender equality have taken big steps backwards. This we must address”, Kronman

emphasised.

About this note

This is a summary note of the virtual seminar The Nordic contribution to EU-Africa cooperation in times of threatened multilateralism held on 30 November 2020. Thought leaders, scholars and policymakers from Africa and Europe discussed the need to strengthen the social contract in Africa, and how the Nordic countries can contribute to the future of EU-Africa relations.

About the Nordic Africa Institute

About the Hanaholmen Swedish-Finnish Cultural Centre External link, opens in new window.

External link, opens in new window.