Rule of law: a tool in China's Africa agenda

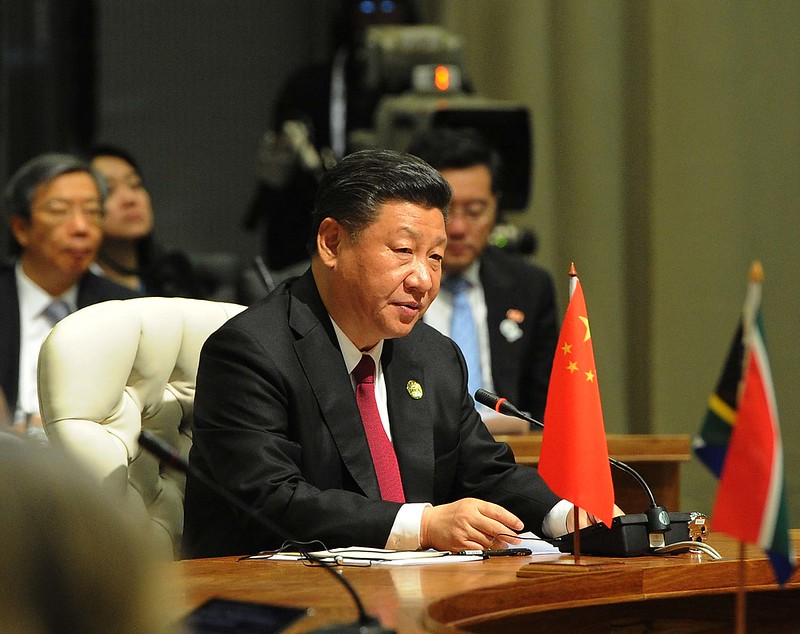

President Xi Jinping of the People’s Republic of China. Photo: Siyabulela Duda, creative commons.

China’s engagement with African states has shifted as economic self-interest trumps strategically motivated generosity. “China has begun to view African partners as a potential liability to investments”, says NAI researcher.

In a virtual meeting on 17 June, Chinese President Xi Jinping and African counterparts discussed how to join forces against the Covid-19 pandemic. But they also discussed economic affairs. If African leaders had expected meaningful debt relief from China, allowing for more resources to combat Covid-19, they were disappointed.

China agreed to write off interest-free bilateral loans, but this may have a limited effect. The loans constitute only nine percent of total Chinese lending to Africa. Other loans are commercial and not up for cancellation.

China holds 20 percent of Africa´s total debt, but according to a report from the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, about half of China’s lending is not accounted for in official statistics. It is therefore difficult to include in international debt relief discussions.

“Limited transparency on loan conditions creates incentives for kickbacks. This has inflated costs for several infrastructure projects in a number of African countries”, NAI researcher Jörgen Levin remarks.

NAI researcher Jörgen Levin.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is safer for countries to rely on. Its mandate is to assist member states in difficult times, such as the current global pandemic. According to Levin, a number of countries are now reverting to the IMF to restructure their debts. The IMF has in fact agreed to temporarily freeze interest payments on outstanding loans to developing countries during the pandemic.

Why are African countries so heavily indebted to China? Chinese loans are not cheaper than other loans, Levin says, but they come without the political obligations often attached to loans from multilateral institutions or Western donor countries.

“Now, however, it seems that China has for some time been slowing down its lending to Africa. It could be they have realised that the risk is high and the return is lower than expected”, Levin notes.

NAI researcher and Southern Africa expert Henning Melber has noted how the Chinese have begun to view their partners in Africa as liabilities to their investments. Chinese diplomats have openly criticised Zimbabwe, in particular, for not getting its economy back on track since Robert Mugabe´s presidency; but also South Africa, after the state capture that occurred under Jacob Zuma.

NAI researcher Henning Melber.

“China is increasingly interested in the rule of law and good governance in Africa. However, this is not about democracy or development, but simply because China is already a big player on the continent, and now wants to protect its investments”, Melber states.

For African countries, little has changed structurally in trade exchange patterns since China launched its Africa programme some 20 years ago, according to Melber.

Investments and loans benefit Chinese companies that bring know-how, qualified workers and material from China. Natural resources are shipped to China from Africa without any value addition through refinement, while manufactured Chinese goods are sold back at a high cost for African countries.

“What we scholars and activists criticised Western development aid for in the 1970s and 1980s, giving with one hand and taking back twice as much with the other, is precisely what China is doing today in Africa”, Melber concludes.

TEXT: Johan Sävström