Can Uganda use high fertility rates to tackle extreme poverty?

School children studying mathematics in Masindi, Uganda. Photo: Matt Lucht

Rapid population growth is a concern for sub-Saharan countries battling extreme poverty. However, with the right focus on education, healthcare and economic transformation states such as Uganda could capitalise on the high fertility rates of the last two decades, NAI researcher David Lawson says.

High population growth is making matters worse for many sub-Saharan countries, with weak economies and a significant proportion of the population living in extreme poverty, classified as households earning less than US$1.90 a day.

However, with government-led policies that build human capital and create jobs, it is possible to capitalise on the high fertility of the last two decades, according to Lawson.

With large young populations comes the potential of a strong workforce that produces economic growth and stability. However, if birth rates remain high, then individual households will continue to struggle to provide for each person in the family, and on a national scale the economic growth per capita will stay low. According to Lawson it is necessary to change age structures, with a decline in fertility and mortality rates, to obtain economic growth, a connection economists refer to as the demographic dividend.

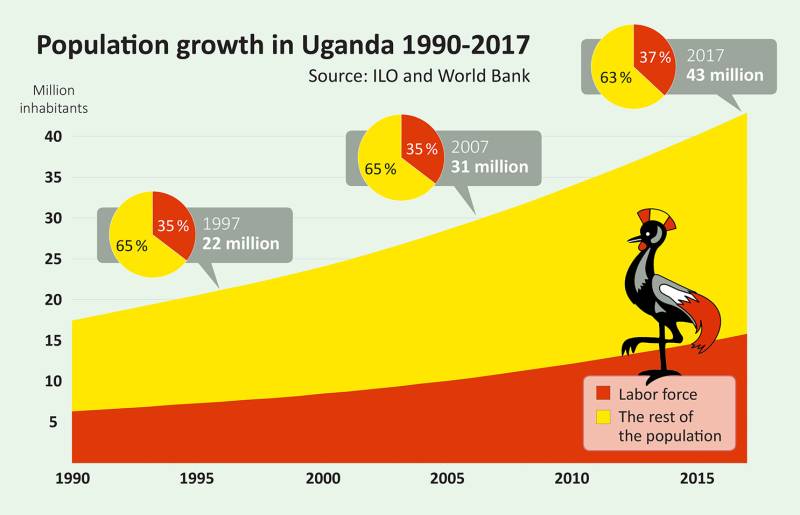

He takes the example of Uganda, which ranks among the top ten countries in the world in terms of population growth according to UN statistics External link, opens in new window.. The population has been growing at an annual rate of 3.0 percent or more since 1978, at which rate it doubles every 20 years.

External link, opens in new window.. The population has been growing at an annual rate of 3.0 percent or more since 1978, at which rate it doubles every 20 years.

David Lawson, Senior Researcher at The Nordic Africa Institute. Photo: Mattias Sköld

Lawson thinks Uganda has the potential to be one of fastest-growing economies in the world again, as it was in the 1990s. Uganda has done well in terms of education, having introduced free primary school education in the early 2000s and free secondary schooling for all Ugandan children in 2007. But despite impressive enrolment figures, the Ugandan government needs to invest more resources in the public school system, according to Lawson. A large proportion of students never make the transition from primary to secondary school.

“This is a big issue, because if you want to take advantage of the demographic dividend you need a fully educated and trained workforce, not just children attending a few years of school,” Lawson says.

Education is important in terms of gender equality, to ensure that both men and women can enter the job market, which in turn is crucial to maximising economic growth. A well-educated female workforce was one of the key factors behind South East Asia’s economic transformation in the 1980s.

Education also has indirect and intergenerational effects, Lawson says. As the educational level in a society goes up, fertility rates and child mortality levels tend to go down. Children of educated parents tend to be healthier and are more likely to enter higher education.

To create a workforce with potential for higher productivity, which then maximises the demographic dividend to produce higher growth per capita, Uganda will need to combine strengthened education with universal health coverage and family planning, according to Lawson.

Illustration: Henrik Alfredsson

He also stresses the need for economic and social reforms that benefit young people, the creation of formal employment and a widened tax base.

“In this way, the tax revenue from formal jobs can finance different key activities such as family planning.”

For Uganda to decrease extreme poverty and move up from being a low-income country to a lower middle-income one, structural transformation of the country’s economy is necessary, according to Lawson.

“Typically, countries develop from agriculture to industrialised manufacturing and then the service sector. But realistically, will a landlocked country like Uganda be able to compete with the manufacturing might of the likes of China? That’s unlikely to happen, at least at the aggregate level.”

However, Lawson thinks that the rules of economic transformation may have changed somewhat.

“The structural adjustment need not necessarily be the same as we have previously understood it, but through added value in terms of being regional or global leaders in niche agriculture, for example. We are talking about processing – not just producing the coffee but processing it, packing it, about moving up the global value chain of agriculture.”

The challenges of agricultural transformation are closely linked with the trend of rapid urbanisation.

”How do we get urbanised youth who are not completing school to produce real-value long-term economic growth? This hasn’t really been done before. We have this old model. It’s important to make agriculture attractive and high value to the youth.”

Considering high fertility rates and the demographic dividend, economic policies need to be rather clever, Lawson says.

“There is no ‘magic bullet’. It is a complex interplay of varying factors.”

TEXT: Mattias Sköld