Unstable situation as Malians go to vote

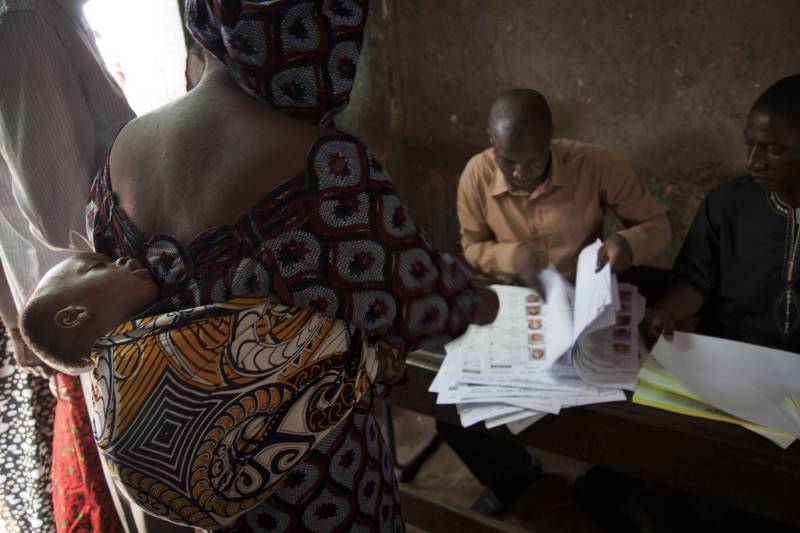

A Malian woman voting in the presidential election in 2013, at the Ecole de la République in the capital Bamako. Photo MINUSMA/Marco Dormino

Should Mali hold elections despite a very unstable security situation? Research Professor Morten Bøås says the West African state is left with only bad options – not going ahead with the poll could lead to a dangerous political vacuum.

Morten Bøås is Research Professor at NUPI, the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs.

As Mali prepares for a presidential election on 29 July, Bøås predicts a voting process “with clear limitations” and says that in parts of the restive north and some central delta areas, people will probably not be able to vote at all.

Mali descended into conflict after a coup in 2012, prompted by concerns over how to deal with a Tuareg rebellion in the country's vast northern desert region. In a recent NAI Policy Note Bøås describes how the situation has gone from bad to worse, with the conflict spilling over from northern to central Mali, despite the conclusion of a peace agreement in Algiers in 2015 and other peacebuilding efforts.

However, a postponement of the election would cause further unrest directed at President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta, who has already been weakened by shrinking popular support and political legitimacy, according to Bøås.

While there are no credible opinion polls, it is clear that many ordinary Malians are unhappy with the worsened security situation and widespread corruption under Keïta’s presidency, Bøås says. In addition, several of the president’s key political allies have joined other factions in the past year.

Will disrupt the vote

According to Bøås, influential armed jihadist insurgents will do what they can to disrupt the election, having already started spreading the message that people should not vote.

“They will certainly exercise control in parts of the north and the central regions’ inner delta areas, but are also likely to attempt attacks in the capital Bamako.

Bøås says that a reasonably credible election process could restore public trust in the state and the political system. The Malian system uses the French model of two rounds of elections. If there is no clear winner during the first round – getting more than 50 per cent of the vote – the two leading candidates will head for a run-off.

“From a stability standpoint, a decisive result in the second round might be the best outcome. An easy win for the sitting president in the first round could prompt accusations of fraud. A close win for either candidate in the second round could lead to political mobilisation in the streets or lengthy court cases, neither of which Mali can afford.”

Failed on both counts

Five years ago Keïta was elected on promises to clean up national politics and secure the government’s territorial integrity over Mali. According to Bøås, he clearly has failed on both counts.

“There are so many things that need to happen in Mali: security reform, judicial reform and economic reform – these processes have almost completely stalled. On top of that there is population growth, climate change and military spending, which has gotten totally out of control.”

Bøås says that a decisive election win for an opposition candidate could perhaps give momentum to stalled processes. However, the opposition appears divided and candidates who represent a new direction are hard to come by, according to Bøås.

Heavy militarisation

“There is a lot of recycling within Mali’s ruling class. Keïta managed to present himself as the new broom when he ran in 2013, but truly he was not.”

Another crucial question relates to Mali’s role among the many international state actors currently operating within its borders as a result of the conflict.

“I am surprised that none of the presidential candidates have raised the question of Malian ownership of the peacebuilding process”, Bøås says.

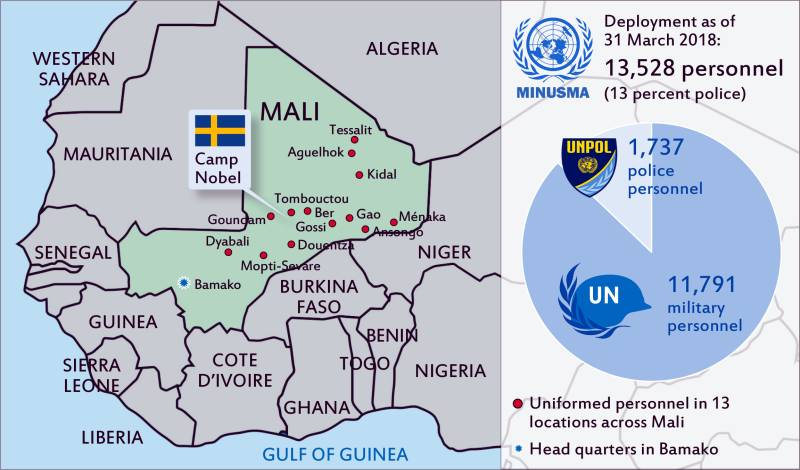

The worsened security situation in Mali in 2012 led to military interventions by France (first Operation Serval and more recently Barkhane), the African Union (AFISMA), and the United Nations (MINUSMA).

Bøås is critical of how international actors have handled the conflict in Mali and how their operations have led to heavy militarisation on the ground.

“Mali needs security, but where security is part of a larger development agenda. Now it is the other way around: it is security first and then comes development.”

“The international operations are heavily shaped by what Europe wants: fewer migrants, fewer traffickers and fewer jihadist insurgents through improved border management. This is not going to solve things for the Malians.”

Opening for talks

A stronger Malian initiative in the peacebuilding process also relates to how ethnic and religious groups in the restive north can be included in the national project. The idea of talking to extremist groups, ruled out so far by the government, has been gaining support among a wide range of political actors within the country.

It was raised at the Conference of National Understanding in Bamako in 2017. At the end of the discussions, the participants – about 300 representatives from the government, opposition, armed groups and civil society – called for open meetings to find out what the jihadists really want.

Bøås says that it might be possible to get jihadist leaders such as Iyad Ag Ghaly and Amadou Koufa to the negotiating table through the help of influential religious figures, such as Mahmoud Dicko, head of the Salafist minority and president of the High Islamic Council of Mali.

“The Malian government would still need its military weight, to enter negotiations from a position of strength. Under any circumstances, the outcome of such talks with jihadists would be uncertain. However, experiences from other African conflicts, like in Liberia and Sierra Leone, show that if you can open some channels, bring out some of the militants, you may have a chance at peace in the long run.”

TEXT: Mattias Sköld

Swedish contingent in Mali

Sweden has contributed 250 military staff to the MINUSMA force since 2014, providing an intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance task force, tactical airlift detachment and national support unit. The majority are based at the Swedish Camp Nobel near Timbuktu in northern Mali.