Brain drain of North African scholars

Lack of available positions and bad working conditions push academics abroad. According to NAI guest researcher Samia Nour, governments in the region do not invest sufficiently in higher education.

Nour is looking into various push and pull factors for the migration of students and researchers from North Africa, including political, economic, demographic and cultural reasons.

“The population is young and growing fast. Many more youths want to study than universities have places. In addition, there are limited job opportunities for the youth. North Africa has one of highest rates of youth unemployment in the world. Moreover, in many North African universities infrastructure and internet availability are not good enough to compete internationally”, Nour points out.

Image: Henrik Alfredsson

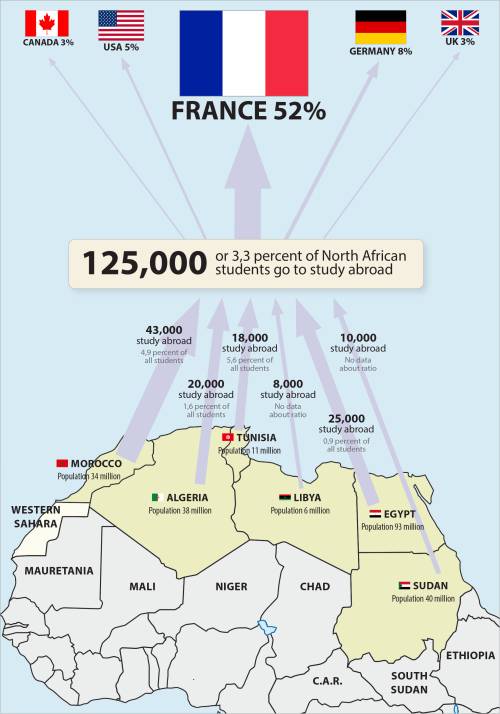

There are also pull factors in play. The countries in the region, especially Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia, have geographical proximity and historical ties to France, which maintained its influence after the end of colonialism, and many people there speak French. Another pull factor is the internationalisation of higher education. To improve their ranking, universities compete to attract international students. This includes universities in France, but well-resourced universities more broadly.

The obvious consequence of a brain drain among students in higher education is a shortage of young trained professionals. These are the very people who are likely to be future drivers of development in North African countries. However, if students return home after graduation, migration may in fact be an advantage because of better educational systems in the host countries.

Moreover, even if they stay to work abroad after graduation, Nour notes, then brain drain is not necessarily a bad thing.

“The money they send home is important for both migrant families and nations’ development. Financial remittances from abroad equal the total sum of foreign direct investment in the region”, Nour observes.

Samia Nour, guest researcher at NAI.

However, brain drain remains a serious problem for North African countries; it is not sustainable to continue lose their young scholars. The governments have also realised this and now stipulate the policy that students with scholarships to study abroad have to come home to work after graduation. Non-returned migrant students are compelled to pay back all costs of their education.

“It is a bit desperate. I think governments could use carrots instead of sticks. Improvements in infrastructure, opportunities for professional development, research funding and scholarships as well as higher salaries for employees would make academics more eager to stay and continue their careers in North Africa”, Nour concludes.

TEXT: Johan Sävström