Unlocking Africa's trade potential

Promises and pitfalls of the African Continental Free Trade Area Agreement

Lagos, Nigeria July 2019. Cranes and containers at the gateway port in Apapa. Photo: Temilade Adelaja, Reuters.

Africa’s countries have agreed to form the world’s largest free trade area, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). The purpose is to create a single market by eliminating trade and labour barriers. This is expected to increase trade both within Africa and with other regions. However, past trade reforms have not been very successful. Moreover, the effects of the AfCFTA may vary greatly from country to country due to differences in political will, capacity and economic structure. The key to making it work is to facilitate trade and reduce non-tariff trade barriers, while taking into account the diversified political and economic context.

By Jörgen Levin, Assem Abu Hatab and Stephen Karingi

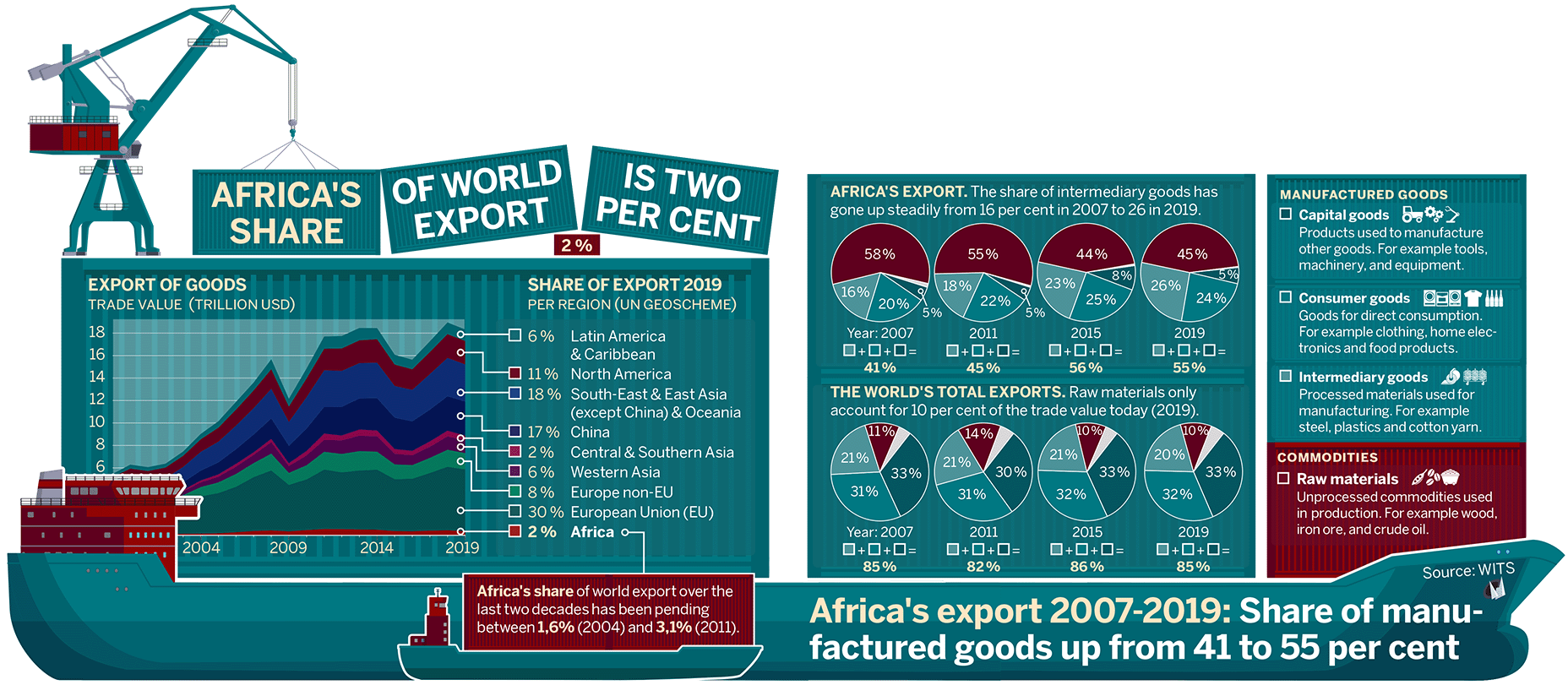

Exports of manufactured goods from developing countries have increased rapidly over the past 30 years, due in part to falling tariffs, declining transport costs, increased specialization and sustained economic growth. This has benefited many developing countries, helping them to make the transition away from a heavy dependence on commodity exports and towards higher value-added exports. However, on the African continent this transition has been slow. Moreover, the continent’s share of global trade fell by 40 per cent between 1970 and 2020. African countries are still at the lower end of global value chains. Exports to the rest of the world are dominated by low value-added commodities, and 45 of Africa’s 55 countries are classified as commodity dependent. Commodity dependence magnifies the region’s exposure to global commodity price shocks and causes economic volatility, political instability, high illicit flows and low human development.

Given the right conditions, openness to trade offers opportunities for African countries to accelerate economic growth, diversify their exports and reduce their commodity dependence. International trade enables them to specialize in sectors where they perform relatively well. Trade also offers an opportunity to be part of regional or global value chains, where economies of scale, new technologies and knowledge creation have long-lasting positive effects on economic development. Trade enables African countries to diversify their economies, to produce a wider range of goods and services, and to provide productive employment and decent work. Productive employment on a large scale is necessary for the continent’s countries to harness the demographic dividend offered by their rapidly growing youthful population. New employment opportunities, combined with policies that address gender barriers, provide an opportunity to narrow the gender income gap.

The shortcomings of previous trade reforms

Regional integration has long been an important instrument for African governments to cooperate and harmonize their policies, in order to achieve sustainable development. The establishment of Africa’s regional economic communities (RECs) – which in some cases, like the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), date back to the 1970s – has facilitated a regional governance structure that is able to aggregate diverse national and regional-level interests on the continent. The mandates of the RECs include broad areas such as peace, security, development and economic integration; but the lack of accountability and enforcement mechanisms has made it difficult for them to meet their goals. When it comes to trade, the achievements of the RECs have often been disappointing. The reasons for this include piecemeal integration of goods, labour and capital markets, and domestic and multilateral trade policies that have trumped regional trade policies.

From the early days of independence until the early 1990s, many African governments implemented an inward-looking trade strategy, based on the assumption that protectionist policies would help the continent’s countries build up their own industries. However, this largely failed. The economic reform programmes that followed included a shift towards an export-oriented trade strategy. A key objective of the reforms was to provide incentives to promote exports; but poor business environments and infrastructure prevented the countries from fully exploiting the potential of trade. A large number of African countries experienced deindustrialization, which reduced employment opportunities, especially for the youth. In resource-rich countries, commodity dependence increased and preserved an economic structure that reinforced poverty and inequality.

To sum up, previous attempts – irrespective of whether they had a regional, a domestic or a multilateral focus – failed either to increase intra-African trade significantly or to enhance trade with the rest of the world in products with a higher value-added component. The RECs and the multilateral trade reforms managed to reduce import tariff rates both within Africa and between African countries and the rest of the world. However, cumbersome domestic customs requirements and inadequate internal and cross-border infrastructure make it very costly to trade on the African continent. According to estimates from the International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development (ICTSD) External link, opens in new window., these trade barriers add an average cost to African trade of 283 per cent. In addition, trade-related binding constraints – such as weak productive capacity, high transport costs, low access to trade credit and difficulty in connecting producers to markets – have also added to the challenge of maximizing the benefits of trade.

External link, opens in new window., these trade barriers add an average cost to African trade of 283 per cent. In addition, trade-related binding constraints – such as weak productive capacity, high transport costs, low access to trade credit and difficulty in connecting producers to markets – have also added to the challenge of maximizing the benefits of trade.

Far-reaching scope

The AfCFTA agreement offers the potential to redesign Africa’s trade patterns. Economists and analysts have often seen intra-African trade as less attractive to African countries than trade with the rest of the world. Their view has been that African markets are small in terms of purchasing power and that many African countries produce similar types of goods, which reduces trading opportunities. However, recent evidence External link, opens in new window. suggests that intra-African trade is higher and more diversified than previously thought. Promoting intra-African trade has the potential to deepen regional value chains and make them more competitive. Large cross-border trade flows between African countries are predominantly undertaken by small-scale female traders. Reducing trade barriers will make trade safer for these women.

External link, opens in new window. suggests that intra-African trade is higher and more diversified than previously thought. Promoting intra-African trade has the potential to deepen regional value chains and make them more competitive. Large cross-border trade flows between African countries are predominantly undertaken by small-scale female traders. Reducing trade barriers will make trade safer for these women.

The AfCFTA agreement is unique for several reasons:

- Firstly, it is the largest free trade area in the world, covering 54 of the African Union’s 55 member states, with a combined population of over 1.3 billion people and total GDP of over USD 3.4 trillion. Additionally, the AfCFTA agreement is comprehensive. It covers not only trade in goods, but also services, investment, competition policy and intellectual property rights. A further two protocols on digital trade and on women and youth in trade are being finalized. These will make it more far-reaching than previous trade agreements in Africa, which have tended to focus primarily on goods.

- Secondly, the AfCFTA agreement is ambitious in its goals, aiming to create a single market for goods and services in Africa, in preparation for an African customs union with free movement of people and capital. It seeks to promote economic integration and diversification, foster industrial development and enhance Africa’s bargaining power in international trade negotiations.

- Thirdly, the AfCFTA agreement is development-focused, designed to promote economic growth and shared prosperity by creating a larger market for African goods and services, reducing trade barriers and fostering greater regional integration. The agreement is also unique, in that it is an African-led initiative, reflecting the continent’s priorities and interests, and building on existing regional trade agreements.

- Finally, the AfCFTA agreement has established institutional mechanisms, such as the AfCFTA Secretariat, to support its implementation and monitoring, and it includes provisions on technical assistance, capacity building and financing to help African countries implement the agreement and realize its benefits.

In order to fully realize the gains of the AfCFTA, trade barriers need to be reduced and complemented with measures that facilitate trade. Eliminating tariffs will be relatively easy, as tariffs on intra-African trade are already low. Reducing non-tariff measures and implementing trade-facilitation measures will be harder and will require policy reforms at the regional and national level. African governments need both to invest in “hard” infrastructure (energy, transportation and communication) and to fully implement the competition policy and intellectual property-rights protocols of the AfCFTA for an optimal “soft” infrastructure that includes (among other things) quality enhancement of domestic regulations, equitable and enforceable competition policy, and legal and judicial procedures under the dispute-settlement protocol of the agreement. The investment in both hard and soft infrastructure was insufficient in the implementation of previous regional integration initiatives External link, opens in new window..

External link, opens in new window..

High expectations, great variations

There are high expectations of the economic impact of the AfCFTA. If the efforts to spur intra-regional trade are implemented in line with ongoing negotiations, the World Bank estimates External link, opens in new window. that the volume of total African exports will increase by 29 per cent by 2035. Intra-continental exports will increase by more than 81 per cent, and exports to non-African countries by 19 per cent. More conservative estimates by the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA)

External link, opens in new window. that the volume of total African exports will increase by 29 per cent by 2035. Intra-continental exports will increase by more than 81 per cent, and exports to non-African countries by 19 per cent. More conservative estimates by the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) External link, opens in new window. forecast that by 2045, intra-African trade will be 34 per cent higher than the baseline scenario without the AfCFTA. The agreement is forecast to result in a major boost to intra-African trade in food and other industries supporting structural transformation across Africa. As well as the significant increases in exports, there are smaller gains to be had with regard to incomes: according to the World Bank

External link, opens in new window. forecast that by 2045, intra-African trade will be 34 per cent higher than the baseline scenario without the AfCFTA. The agreement is forecast to result in a major boost to intra-African trade in food and other industries supporting structural transformation across Africa. As well as the significant increases in exports, there are smaller gains to be had with regard to incomes: according to the World Bank External link, opens in new window., the AfCFTA has the potential to increase real incomes by 7 per cent by 2035 and to lift 40 million people out of extreme poverty. Still, to achieve these potential gains, African governments need to eliminate import tariffs, reduce non-tariff measures and facilitate trade by removing the long delays at borders and reducing administrative costs to a minimum. Taking into account the larger inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) and investment in soft infrastructure, real incomes could even increase by up to 9 per cent by 2035. However, the real income gains and the poverty-reduction effects of the AfCFTA will vary greatly from country to country: the World Bank predicts that they will be over 10 per cent for Cote d’Ivoire, Zimbabwe, Kenya, Tanzania and Namibia, but less than 3 per cent for Malawi and Mozambique.

External link, opens in new window., the AfCFTA has the potential to increase real incomes by 7 per cent by 2035 and to lift 40 million people out of extreme poverty. Still, to achieve these potential gains, African governments need to eliminate import tariffs, reduce non-tariff measures and facilitate trade by removing the long delays at borders and reducing administrative costs to a minimum. Taking into account the larger inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) and investment in soft infrastructure, real incomes could even increase by up to 9 per cent by 2035. However, the real income gains and the poverty-reduction effects of the AfCFTA will vary greatly from country to country: the World Bank predicts that they will be over 10 per cent for Cote d’Ivoire, Zimbabwe, Kenya, Tanzania and Namibia, but less than 3 per cent for Malawi and Mozambique.

The AfCFTA is expected to redistribute incomes. Estimates suggest that wages for unskilled labour should grow more rapidly than for skilled labour in East, West and Central Africa. However, the opposite is expected in North Africa, as the labour market structure there is different from the other regions. Women’s wages are expected to grow faster than men’s in most regions (except Southern Africa) as female-labour-intensive sectors benefit from the agreement. Still, African labour markets are gender segregated and additional policies to support equal opportunities will be needed to fully realize these gains. The agreement’s protocol on women and youth in trade will be an important step in helping to remove barriers that constrain women and young people – as both workers and entrepreneurs – from realizing the gains of the AfCFTA.

In the short term, trade reforms will lead to adjustment costs and job losses in contracting sectors. Complementary public social protection policies will be needed, but funding them will be a challenge, as the agreement will have an adverse impact on tax revenue. The AfCFTA Adjustment Fund, which aims to support member states’ tax revenue losses, is an important complement to the reforms. Broadened social-protection programmes can provide short-term assistance, but investment in human capital (including training opportunities for women and youth) and improved access to productive assets are also important in exploiting the new income opportunities. Unequal opportunities create the risk that income gaps and related inequalities – particularly with regard to gender and age – could widen.

Role of development partners

Development partners should support the African Union (AU) and its partners in the overall process of implementing the agreement. The establishment of the AfCFTA shows that the political will exists to make this happen; however, African countries face many challenges in implementing the agreement and maximizing its benefits. Of relevance is how African countries can work with their international partners to ensure that the AfCFTA agreement is compatible with existing trade agreements.

Ever since the launch of the Aid for Trade Initiative in 2006, development partners, including the World Trade Organization (WTO), have supported African governments with significant amounts of official development assistance to help build trade capacity and boost investment in trade-related infrastructure. Although opinions differ, overall the empirical evidence suggests that supporting trade-related infrastructure has been effective in promoting the exports of both recipients and donor countries. The impact on productive capacity and export diversification has been smaller, but it tends to be more visible if countries improve their institutional and governance quality. International trade generally helps to reduce poverty in countries where the financial sector is deep, education levels are high and institutions are strong. Therefore, support for a trade-related development agenda still needs to focus on development challenges, such as weak productive capacity, access to credit, low human capital and difficulty in connecting producers to markets – all of which adds to the challenge of maximizing the benefits of trade. These challenges vary across Africa, and individual country case studies are needed, so that different approaches can be designed that take into account the diversified political context.

Policy recommendations

- Reduce cost of trade: Trade barriers in Africa are very costly in terms of forgone income. For governments and institutions implementing the AfCFTA, it is therefore important to remove tariffs, reduce non-tariff barriers and continue to implement reforms that facilitate trade. To tackle the challenges related to trade facilitation, governments and customs and border agencies need to make the necessary changes to existing laws and regulations, and to enhance the efficiency of operational procedures at border posts and ports.

- Set up an AfCFTA strategy: Opening an economy up to greater trade can have significant effects on its domestic industries, labour markets and overall structure. A strategy will help it respond to these effects and to take advantage of the opportunities. Examples of common adjustments that accompany trade reforms include: deregulation; labour market reforms; and infrastructure, connectivity and human capital. Policymakers need to consider carefully the potential costs and benefits of the reforms and to work to mitigate any negative impact on vulnerable populations.

- Remember that African economies are very different: Economic structures, trade patterns, politics and constraints on expanding trade and promoting economic growth differ a lot from country to country in Africa. In order to maximize the gains from the AfCFTA, each African government needs to identify and tackle the worst constraints that affect the strength of its country’s competitiveness. AfCFTA National Strategies are essential if the AfCFTA is to be incorporated into national development plans and policies.

- Development partners should continue their support: Ever since the Aid for Trade Initiative was launched in 2006, Nordic development partners have supported the efforts of African countries to increase their exports, and they should continue to do so at both the national and the regional level, together with the AU and its partners. A successful trade-focused development agenda builds on the assumption that aid and trade are complementary. Trade alone has never been a silver bullet for successful development; but in conjunction with investment in human capital and a conducive policy environment that includes strong and effective institutions, there are potentially huge opportunities for African countries to make a big leap forward.

Further reading

The NAI policy notes series is based on academic research. For further reading on this topic, we recommend the following titles:

- Adetula, V., R. Bereketeab, L. Laakso and J. Levin (2020). The legacy of Pan-Africanism in African integration today

External link, opens in new window.. NAI Policy Notes 2020:9. The Nordic Africa Institute.

External link, opens in new window.. NAI Policy Notes 2020:9. The Nordic Africa Institute. - McKay, A., Ogunkola, O. and Semboja, H. H. (2023). Rethinking regional integration in Africa for inclusive and sustainable development: Introduction to the special issue

External link, opens in new window.. The World Economy Vol. 46 Issue 2. Wiley.

External link, opens in new window.. The World Economy Vol. 46 Issue 2. Wiley. - Mold, A. and S. Chowdhury (2021). Why the extent of intra-African trade is much higher than commonly believed – and what this means for the AfCFTA

External link, opens in new window.. Africa in Focus. Brookings.

External link, opens in new window.. Africa in Focus. Brookings. - Sommer, Lily, and David Luke (2016). Priority Trade Policy Actions to Support the 2030 Agenda and Transform African Livelihoods

External link, opens in new window.. Geneva: International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development (ICTSD).

External link, opens in new window.. Geneva: International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development (ICTSD). - World Bank (2020). The African Continental Free Trade Area – Economic and Distributional Effects. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development

External link, opens in new window.. Washington, DC.

External link, opens in new window.. Washington, DC.

NAI Policy Notes are a series of research-based briefs on relevant topics, intended for strategists and decision makers in foreign policy, aid and development. They aim to inform and generate input to the public debate and to policymaking. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute. The quality of the series is assured by internal peer-review processes and plagiarism-detection software.

About the authors

- Jörgen Levin is a senior researcher at the Nordic Africa Institute. His fields of research are macroeconomics, inclusive growth and taxation, with a focus on East Africa.

- Assem Abu Hatab is a senior researcher at the Nordic Africa Institute. His research focuses on the economics of natural resources and food systems in Africa.

- Stephen Karingi is the Director of the Regional Integration and Trade Division at the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA).

How to refer to this policy note:

Levin, Jörgen; Abu Hatab, Assem; Karingi, Stephen (2023). Unlocking Africa's trade potential: Promises and pitfalls of the African Continental Free Trade Area Agreement. (NAI Policy Notes, 2023:2). Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:nai:diva-2861 External link, opens in new window.

External link, opens in new window.