AfCFTA will lead to uneven gains for members

The Rubavu-Goma border crossing between Rwanda and DR Congo. Trade facilitating actions such as cutting red tape at border controls is expected to have a positive impact on economic growth on the continent. Photo: Simone D. McCourtie / World Bank

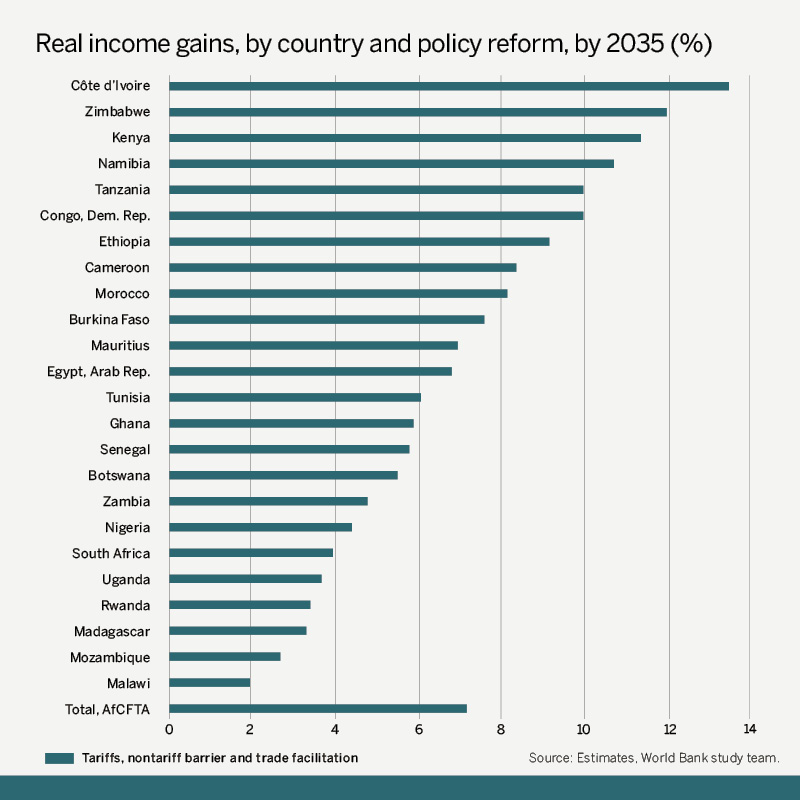

The removal of trade barriers in the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), launched this year, will affect member states very differently, according to NAI researcher Jörgen Levin. Côte d’Ivoire, Zimbabwe and Kenya top the list of states that are likely to benefit greatly. Malawi, Mozambique and Madagascar are likely to see relatively small effects.

The objective of the AfCFTA is to create a single market and deepen economic integration on the continent. Studies indicate that removing trade barriers between AfCFTA members is likely to have a positive impact on economic growth on the continent. The biggest benefits will come from so-called trade facilitating actions, such as cutting red tape at border controls.

Other reforms, such as the removal of tariffs, will have a smaller effect. The reason is that much of the work of removing tariffs has already been done by regional economic communities. For example, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) began a programme of tariff reductions in 2001.

The reforms would affect the AfCFTA’s 54 member countries very differently, Levin explains. According to a scenario analysis by the World Bank External link, opens in new window., real income gains in Côte d’Ivoire would be 13 percent higher by 2035 compared to a scenario without AfCFTA. In Zimbabwe, the effect would be 12 percent; in Kenya, Namibia, Democratic Republic of Congo and Tanzania around 10 percent. Madagascar, Malawi, and Mozambique, however, are clustered around an expected gain of 2 percent.

External link, opens in new window., real income gains in Côte d’Ivoire would be 13 percent higher by 2035 compared to a scenario without AfCFTA. In Zimbabwe, the effect would be 12 percent; in Kenya, Namibia, Democratic Republic of Congo and Tanzania around 10 percent. Madagascar, Malawi, and Mozambique, however, are clustered around an expected gain of 2 percent.

Jörgen Levin.

“The winners typically are countries with a large and diversified manufacturing sector. Those at the bottom tend to be countries with a low level of industrialisation”, Levin says.

But other factors come into play as well. South Africa, which has the continent’s most developed manufacturing sector, scores relatively low, with an expected added income gain of 4 percent.

The reason is that SADC, the regional economic community of which South Africa is a member, has already come a long way in integrating the economies of the region, which would make additional gains from the AfCFTA relatively limited.

Levin points out that the World Bank’s analysis is based on relative prices which means that high-inflation countries such as Zimbabwe could still benefit from AfCFTA in the scenario. The analysis assumes that the trade agenda is fully implemented without political blockages of reforms.

Levin stresses that trade in itself is not a key driver of economic growth. It is the indirect effects from trade that can lead a country towards a path of sustainable high incomes.

Open economies have a better chance of attracting investment and new technology. When foreign technologies are adopted they can contribute to economic growth if a country has a sufficient level of human capital. If trade can lead to reallocation of resources from unproductive to highly productive sectors, then that would also have a positive impact on economic growth.

While trade reforms can be important drivers for economic transformation, it is important to be realistic about what the AfCFTA can achieve, Levin points out. Even countries that benefitted the most would report modest annual income gains of 1 percent per year.

The success of the AfCFTA’s project to remove trade barriers also depends on the level of commitment among African governments, according to Levin. When African countries removed trade barriers in the 1990s, many of them were quick to put them back to protect national industries.

“The standard solution is to open up the market in order to stimulate exports and economic growth, while at the same time supporting and compensating those at the losing end. The problem is that most African states lack the social welfare systems and economic resources to do so”.

TEXT: Mattias Sköld

Illustration: Fredrik Swahn