A step forward, but no guarantee of gender-friendly policies: Female candidates spark hope in the 2020 Ghanaian elections

.jpg)

Kasoa, Ghana, 2020. People on a balcony overlooking a political rally. Photo: NDC

In the forthcoming Ghanaian elections, for the first time ever a woman has emerged as a vice-presidential candidate for one of the two major parties. Her candidacy has given rise to hopes of progress on gender equality issues, but it has also led to anti-feminist and misogynistic comments. This policy note addresses certain challenges and opportunities to break the male dominance of Ghanaian politics.

Policy note by Diana Højlund Madsen, senior researcher at NAI, Kwesi Aning External link, opens in new window., full professor and director at the Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre and Kajsa Hallberg Adu, post-doctoral researcher at NAI

External link, opens in new window., full professor and director at the Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre and Kajsa Hallberg Adu, post-doctoral researcher at NAI

What’s new?

In the upcoming Ghanaian elections, a woman has, for the first time, emerged as a vice-presidential candidate for one of the two major parties in the country. Her candidacy has sparked hopes of progress on gender equality, but has also triggered anti-feminist and misogynistic rhetoric.

Why is it important?

Ghana is one of Africa’s most stable democracies. Since the establishment of the fourth republic in 1992, restoring multiparty politics, Ghana has held six democratic elections and the country’s presidency has changed party three times. However, in terms of equal gender representation, with only 14 per cent female members of parliament, the country is lagging behind many other African states – and indeed is well below the continental average of 24 per cent. The much-debated Affirmative Action Bill, introduced back in 2016, has been delayed by fierce resistance. Seen in this light, a woman emerging in a central role in Ghanaian politics is significant.

What should be done and by whom?

This policy note assesses the effects of violence, violent rhetoric and other problematic aspects of masculinity in the election processes within parties. The aim is to give civil society organisations, election observers, and policy makers working with democracy and gender equality issues some research-based recommendations on how to adapt their strategies and action plans to the opportunities and threats of the ongoing election process and beyond.

Ghana has been hailed for its democratic elections, but female representation is low at all levels of politics. Currently, female MPs account for 14 per cent (38 out of 275 parliamentary seats). During the 2019 local elections, women won only 4 per cent of seats. However, the naming of a female running mate by the main opposition presidential candidate in the 2020 election raises hopes for increased gender inclusiveness. This has shifted the election dynamics from a presidential competition between two ‘big men’ to focus on gender aspects of politics.

The policy note concludes that, although the selection of a female running mate is important both in terms of numbers (descriptive representation) and in providing a role model (symbolic representation), it is imperative that, for women’s representation to be meaningful, there must be gender-friendly policies (substantive representation).

Breaking the glass ceiling

In July 2020, Professor Naana Jane Opoku-Agyemang, first female vice-chancellor of the University of Cape Coast and Ghana’s former minister of education, was selected by John Dramani Mahama, presidential candidate for the National Democratic Congress (NDC), as his running mate, thus opening up the possibility of challenging the existing patriarchal structures in politics. This is the first time that a woman has appeared on the presidential ticket for either of the two main parties. Since the first elections of the fourth republic were held in 1992, power has alternated between the two major parties, the NDC and the ruling New Patriotic Party (NPP). In the 2016 election, these two parties garnered more than 98 per cent of the votes, making Ghana in effect a duopolistic system.

There are other top female candidates in the elections – for example, Brigitte Dzogbenuku of the Progressive People’s Party (PPP) and Nana Konadu Agyeman-Rawlings of the National Democratic Party (NDP). The latter was the wife of ex-President Jerry Rawlings and was Ghana’s first lady for almost two decades. She was also the leader of the 31st December Women’s Movement, which played a pivotal role in the mobilisation of women for the 1992 and 1996 elections. Nevertheless, if women want to be elected, they have to join the contest where the power lies – in the NPP or the NDC, thus reinforcing the two-party structure.

Increased awareness of gender issues

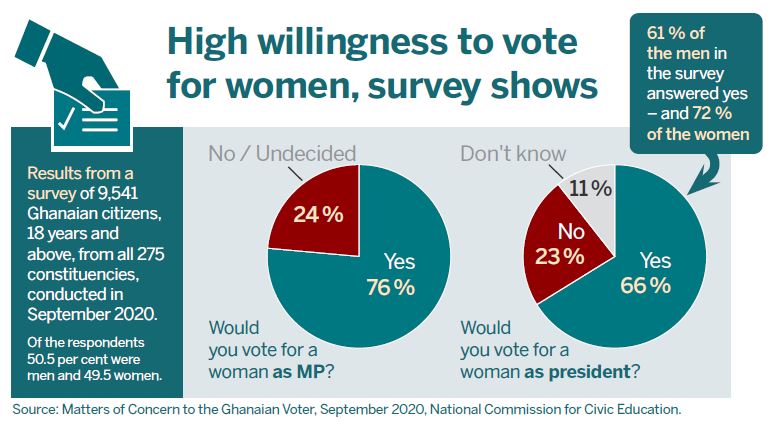

Ghanaians want a more inclusive democracy. According to a recent report by the National Commission for Civic Education (NCCE) External link, opens in new window., 66 per cent of voters are willing to cast their ballot for a female president and 76 per cent for a female member of parliament. The media have also elevated the issue of women’s representation, for instance in the TV programme 2020 Woman on channel GHOne. Furthermore, international bodies have sought to raise awareness surrounding gender in politics, for example by appointing incumbent President Akufo-Addo as the AU gender champion in 2017.

External link, opens in new window., 66 per cent of voters are willing to cast their ballot for a female president and 76 per cent for a female member of parliament. The media have also elevated the issue of women’s representation, for instance in the TV programme 2020 Woman on channel GHOne. Furthermore, international bodies have sought to raise awareness surrounding gender in politics, for example by appointing incumbent President Akufo-Addo as the AU gender champion in 2017.

Substantive representation requires gender issues to be part of the political agenda. Research by Højlund Madsen shows that female political candidates employ different strategies and refer to ‘gender’ in different ways in their campaigning: they may appeal to the ‘newness’ of getting women into office; emphasise the ‘qualitative difference between male and female leaders’, for example with a view to uniting and building empathic cooperation and ‘accommodating men’s needs and interests’; or focus on the common interest in women’s economic empowerment to benefit the household.

Gender profiling of political parties

In its 2020 manifesto, the NDC outlined a list of gender issues, with a focus on violence against women and women’s access to land. The party also promised the adoption of a 30 per cent quota of appointments for women and approval of the much-debated bill for affirmative action measures for women External link, opens in new window.. If the NDC wins the election, the women’s organisations will expect it to deliver on its promises and address the substantive gender issues.

External link, opens in new window.. If the NDC wins the election, the women’s organisations will expect it to deliver on its promises and address the substantive gender issues.

Researcher Melody E. Valdini (2019) proposes the notion of ‘inclusion calculation External link, opens in new window.’, implying that political parties are rational actors, who will calculate whether the inclusion of women in politics will increase their chances of winning elections. For the NPP, gender has not been a winning issue. President Akufo-Addo has had to apologise for the delay in getting the Affirmative Action Bill through parliament. Moreover, the NPP initiative to protect candidacies in the 16 constituencies where a woman was already in place created turmoil before the 2016 election and was eventually taken off the table. In particular, male opponents in the constituencies affected argued that some of the women were not that popular; that the NDC could put up a stronger (male) candidate to win the seat; that is could become a permanent measure and, that it meant handing women a seat without them making any efforts (the latter despite the fact that they still had to contest other women and the opposition candidate.

External link, opens in new window.’, implying that political parties are rational actors, who will calculate whether the inclusion of women in politics will increase their chances of winning elections. For the NPP, gender has not been a winning issue. President Akufo-Addo has had to apologise for the delay in getting the Affirmative Action Bill through parliament. Moreover, the NPP initiative to protect candidacies in the 16 constituencies where a woman was already in place created turmoil before the 2016 election and was eventually taken off the table. In particular, male opponents in the constituencies affected argued that some of the women were not that popular; that the NDC could put up a stronger (male) candidate to win the seat; that is could become a permanent measure and, that it meant handing women a seat without them making any efforts (the latter despite the fact that they still had to contest other women and the opposition candidate.

The NDC has calculated the benefit of highlighting the party’s gender profile, which by researcher George-Bob Miliar (2020) has been characterised as ‘a strategic move’ External link, opens in new window.. In Naana Jane Opoku-Agyemang the NDC chose an intellectual candidate and avoided certain male candidates whose past credentials could be criticised.

External link, opens in new window.. In Naana Jane Opoku-Agyemang the NDC chose an intellectual candidate and avoided certain male candidates whose past credentials could be criticised.

No political will for affirmative action

Since 2011, successive presidents – from the NPP and the NDC alike – have set aside the Affirmative Action Bill, despite paying lip service to it. In both parties, there is continued resistance to affirmative action measures in favour of women. Meanwhile, the Affirmative Action Bill has undergone extensive consultation, with the bureaucratic toing and froing delaying its adoption and gradually softening its language.

The women’s organisations have gotten together to agitate for the adoption of the Affirmative Action Bill and has formed a coalition. Furthermore, they have demonstrated in the major cities under the slogan ‘Enough of the rhetoric – pass the Affirmative Action Bill’ and has campaigned on social media under the hashtag #EachforEqual. However, President Akufo-Addo has pinned the blame for the delay on women themselves, claiming at the 2019 Women Deliver conference External link, opens in new window. that there is not enough dynamism and activism. His response was widely condemned for disregarding the structural barriers to women’s participation.

External link, opens in new window. that there is not enough dynamism and activism. His response was widely condemned for disregarding the structural barriers to women’s participation.

The work on the Affirmative Action Bill has illustrated the shortcomings of the national gender machinery as an institution where women can insert feminist claims even though it is spearheading the work. The Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection suffers from underfunding and too broad a mandate: by lumping together gender, children and social protection, there is a risk of gender being swamped by the other issues. Furthermore, the fact that the minister for gender, children and social protection recently changed has resulted in further delays to the Affirmative Action Bill.

Currently, the debate revolves around various affirmative action proposals: one is to pragmatically raise the number of seats in parliament and reserve the extra mandates for women; another is to get the political parties to reserve ‘safe seats’ for women in their strongholds (for example, in the case of the NDC that would be the Volta region and the northern part of the country; for the NPP it would be the Ashanti region).

In 2020, only 48 female candidates are running for parliament – fewer than in 2016. This makes it unlikely that the number of female MPs will increase – and indeed it may even fall.

The monetarisation of politics

A report from the Westminster Foundation for Democracy (WFD) External link, opens in new window. has documented the fact that the cost of running for political office in Ghana rose by nearly 90 per cent the 2012 and the 2016 elections. The cost of politics has increased because of Ghana’s clientelistic relations: the report speaks of unattributed ‘other costs’ that are related to ‘giving gifts’ or other ‘expressions of gratitude’ – known by the electorate as the ‘cocoa season’.

External link, opens in new window. has documented the fact that the cost of running for political office in Ghana rose by nearly 90 per cent the 2012 and the 2016 elections. The cost of politics has increased because of Ghana’s clientelistic relations: the report speaks of unattributed ‘other costs’ that are related to ‘giving gifts’ or other ‘expressions of gratitude’ – known by the electorate as the ‘cocoa season’.

There are four key components of election spending: campaigning, donations, party workers and media/advertising. Expenditure by women is lower than that of men on all these components, except for the last one; this serves to illustrate the need for women to improve their visibility in a male-dominated media sector. A study by Højlund Madsen (2019) shows that there is a need to build up ‘women’s financial muscles’, as they are in a less favourable economic situation and to a large extent have to negotiate with their spouses over expenditure. The receipt of donations is all part and parcel of political fundraising; but for women candidates, the practice leaves them wide open to rumours of transactional sexual favours.

Lack of funding also presents a collective challenge for the women’s organisations, due to Ghana’s changed status (since 2015) as a lower middle-income country and a focus on ‘Ghana Beyond Aid’.

There is no reason to expect that electoral costs will be any lower in 2020.

Politics of insult, ridicule and rumour

Informal institutions – in the form of social shared rules without official sanctions, impede women in politics. For example, when Naana Jane Opoku-Agyemang emerged as the female running mate of the NDC’s presidential candidate, the NPP’s Ashanti regional chairman questioned her looks and labelled her a ‘witch’. In a country where belief in witchcraft prevails and where witch camps exist, it can potentially be dangerous to be associated with supernatural powers. In addition, by focusing on the physical appearance of high-level female politicians – for example, by commenting on the make-up of female MPs, rather than on their politics – critics seek to undermine their professional skills and political messages. Similarly, both the former and the current (female) heads of the Electoral Commission (EC) – Charlotte Osei and Jean Mensa – have been accused by political opponents literally of ‘being in bed’ with the former/present government, following problems with the voter register related and a lack of trust in the EC. These tactics and strategies serve to intimidate and exclude women from politics.

Gendered access to the media

The ability to get the message across is important for every politician. Radio and TV are the main sources of political news, but social media platforms such as Facebook and WhatsApp follow closely behind. According to a report compiled by the independent, non-governmental Media Foundation for West Africa (MFWA), only 17 per cent of radio programming includes women External link, opens in new window..

External link, opens in new window..

A report on the impact of social media on politics in Ghana External link, opens in new window. by Elena Gadjanova and others (2019) shows that debates on social media help to set the agenda and to shape the content of traditional media coverage, and also that the young and well educated rely more on social media than do other groups. Access to internet – especially through mobile connections – is growing, but data transfer remains expensive, which serves to exacerbate inequalities. Men spend more money than women on internet access, and a larger share of women do not use mobile data at all. Women account for 36.5 per cent of activity on Facebook, compared to 63.5 per cent for men, according to a West Africa internet rights report

External link, opens in new window. by Elena Gadjanova and others (2019) shows that debates on social media help to set the agenda and to shape the content of traditional media coverage, and also that the young and well educated rely more on social media than do other groups. Access to internet – especially through mobile connections – is growing, but data transfer remains expensive, which serves to exacerbate inequalities. Men spend more money than women on internet access, and a larger share of women do not use mobile data at all. Women account for 36.5 per cent of activity on Facebook, compared to 63.5 per cent for men, according to a West Africa internet rights report External link, opens in new window. by Media Foundation West Africa.

External link, opens in new window. by Media Foundation West Africa.

With Ghana’s voting population predominantly youthful, campaigning on social media can determine electoral outcomes. The already mentioned report by Elena Gadjanova and others (2019) External link, opens in new window. attributes NPP’s 2016 election victory to its social media strategy. Due to COVID-19, more campaigning is happening online. The costs involved – as well as the prevalence of hate speech and online bullying – mean that campaigning online is a further impediment to women’s non-discriminatory engagement.

External link, opens in new window. attributes NPP’s 2016 election victory to its social media strategy. Due to COVID-19, more campaigning is happening online. The costs involved – as well as the prevalence of hate speech and online bullying – mean that campaigning online is a further impediment to women’s non-discriminatory engagement.

Gendered media coverage

Gender imbalances affect not only access to media, but also media coverage. In her doctoral thesis on the media coverage of political candidates, gender researcher Louise Serwaa Donkor External link, opens in new window. shows that the portrayal of female politicians is contradictory, but predominantly negative. This discourages women from active participatory politics. Considering the already discriminatory nature of patriarchal systems, women are often reluctant to expose themselves, their associates and their families to any further abuse and/or danger.

External link, opens in new window. shows that the portrayal of female politicians is contradictory, but predominantly negative. This discourages women from active participatory politics. Considering the already discriminatory nature of patriarchal systems, women are often reluctant to expose themselves, their associates and their families to any further abuse and/or danger.

The language of Ghana’s political debates is often abusive, misogynistic, anti-social and threatening. According to MFWA, which has been monitoring the media during the 2020 Ghana election season, the use of indecent language has increased External link, opens in new window., as has internet vigilantism, a new menace in Ghanaian politics. Partisan bullies, sometimes on the payroll of established politicians, are unleashing psychological abuse against their political opponents, mostly through the social media, spreading falsehoods, innuendoes and rumours. Social media thus become an instrument of manipulation

External link, opens in new window., as has internet vigilantism, a new menace in Ghanaian politics. Partisan bullies, sometimes on the payroll of established politicians, are unleashing psychological abuse against their political opponents, mostly through the social media, spreading falsehoods, innuendoes and rumours. Social media thus become an instrument of manipulation External link, opens in new window., used to intimidate women and discourage them from competing for public office. It also contributes to the normalisation of violence as an accepted feature of political discourse, in spite of the existence of the Vigilantism and Related Offences Act from 2019.

External link, opens in new window., used to intimidate women and discourage them from competing for public office. It also contributes to the normalisation of violence as an accepted feature of political discourse, in spite of the existence of the Vigilantism and Related Offences Act from 2019.

Gendered COVID-19 impacts

Since campaigning started, Ghana has seen an increase in reported cases of COVID-19. Women have been severely affected in three distinct ways External link, opens in new window.: 1) as frontline health workers; 2) on the labour market, as women dominate the informal sector; and 3) through increased pressure, including domestic violence in the home. Besides, the closure of schools and universities affects women more than men, as child care generally falls to the women in a household. Such gendered effects of the pandemic could prevent women from participating in political activities.

External link, opens in new window.: 1) as frontline health workers; 2) on the labour market, as women dominate the informal sector; and 3) through increased pressure, including domestic violence in the home. Besides, the closure of schools and universities affects women more than men, as child care generally falls to the women in a household. Such gendered effects of the pandemic could prevent women from participating in political activities.

Recommendations

- Women’s organisations should continue to lobby to demonstrate the benefits of inclusive governance, including the Affirmative Action Bill, with reference to African regional measures (Maputo Protocol), the Beijing Platform for Action and UNSCR Resolution 1325.

- Women’s organisations should take a more hands-on approach, in order to promote more women in politics, and drawing inspiration from the UK initiative Time To Activate

External link, opens in new window. making funding available for women to campaign.

External link, opens in new window. making funding available for women to campaign. - Political parties should reach a broad, long-term agreement on gender-inclusive governance and strengthen the Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection to ensure adoption of the Affirmative Action Bill.

- Political parties must show zero tolerance of violence and publicly condemn all forms of gender-based violence on all media platforms (including social media) – especially against women in politics during electoral processes.

- International donors and development strategists should support women’s organisations in programmes for political and economic empowerment at lower levels (districts/units) to encourage them to field candidates at the higher levels (parliament).

- Donors should establish checks and balances for funds earmarked for COVID-19, to ensure that the funding reaches the most affected groups, including different groups of women.

- Security services – such as the police and the army – should be sensitised to gendered perspectives of elections, including violence against female candidates.

- With over 6,000 electoral hotspots identified, it is imperative for the statutory security services to ensure security, in order to reduce the fear that women feel when they participate in the voting process.

- More research is needed on the gendered aspects of vigilantism and on how violent language and threats in social media affect women’s political participation.

Publications - research on this topic

The NAI policy notes series is based on academic research. For further reading on this topic, we recommend the following peer-reviewed articles:

- Højlund Madsen, D., Gender, Power and Institutional Change: The role of the formal and informal institutions for women’s political representation in parliament in Ghana

External link, opens in new window., Journal of Asian and African Studies, 2018.

External link, opens in new window., Journal of Asian and African Studies, 2018. - Højlund Madsen, D., Women’s Political Representation and Affirmative Action in Ghana

External link, opens in new window., Policy note, Nordic Africa Institute, 2019.

External link, opens in new window., Policy note, Nordic Africa Institute, 2019. - Højlund Madsen, D., Gendered Institutions and Women’s Political Representation in Africa

External link, opens in new window., Nordic Africa Institute/Zed, 2020a.

External link, opens in new window., Nordic Africa Institute/Zed, 2020a. - Højlund Madsen, D., Gender, Politics and Transformation in Ghana: The role of critical actors

External link, opens in new window., in Fallaci (ed.), Women: Opportunities and Challenges, New York, Nova Science Publishers, 2020b.

External link, opens in new window., in Fallaci (ed.), Women: Opportunities and Challenges, New York, Nova Science Publishers, 2020b.