Women, peace and security in Rwanda – promises and pitfalls

September 2018. A formed police unit (FPU) officer from Rwanda serving with the UN Mission in South Sudan. The Rwandan FPU3 team, specialised in gender protection, consists of 160 members, of whom 50 percent are women. Photo: Nektarios Markogiannis, UN.

With its high level of female representation and its successful reconciliation process after the 1994 genocide, Rwanda has emerged as something of an African and global ‘model’ of gender equality and conflict resolution. But beyond the ‘politics of numbers’ lies a male-dominated structure, where women and feminist thinking have little or no influence. This policy note assesses how Rwanda has adopted UN Security Council Resolution 1325, and offers policy advice on how to break gender barriers in the traditionally masculinist security sector.

Policy note by Diana Højlund Madsen, senior researcher at NAI.

What’s new?

With the UN celebrating the 20th anniversary of its landmark Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security (WPS) this year, the eyes of the world are turning to conflict-ridden countries and regions, in order to assess its successes and failures. Rwanda, with its high level of female representation and its successful post-genocide reconciliation, has emerged as something of an African and global ‘model’ in terms of gender equality and conflict resolution. But beyond the ‘politics of numbers’ lies a masculinist structure in the upper levels of the security sector, where women and feminist thinking have little or no influence.

Why is it important?

Lasting peace requires all groups affected, including women, to take part in conflict resolution and peace negotiations. Yet, men and masculine ideals still dominate the security and peacebuilding sectors. For Africa, as one of the world’s most conflict-ridden continents, it is key to engage both women and men in implementing Resolution 1325 – not just by paying lip service to the WPS agenda, but by reforming the security sector and letting in women at all levels.

What should be done and by whom?

All stakeholders working on, or influencing, the national action plans for Resolution 1325 should adopt a more diversified way of addressing the different needs of the various groups of women. They should focus less on the state’s role, and more on what the women’s organisations can do, especially at the local level. Government agencies and NGOs working with the WPS agenda should promote local initiatives and break the dependency on foreign donor agendas. The Rwandan government should provide core funding from the national budget.

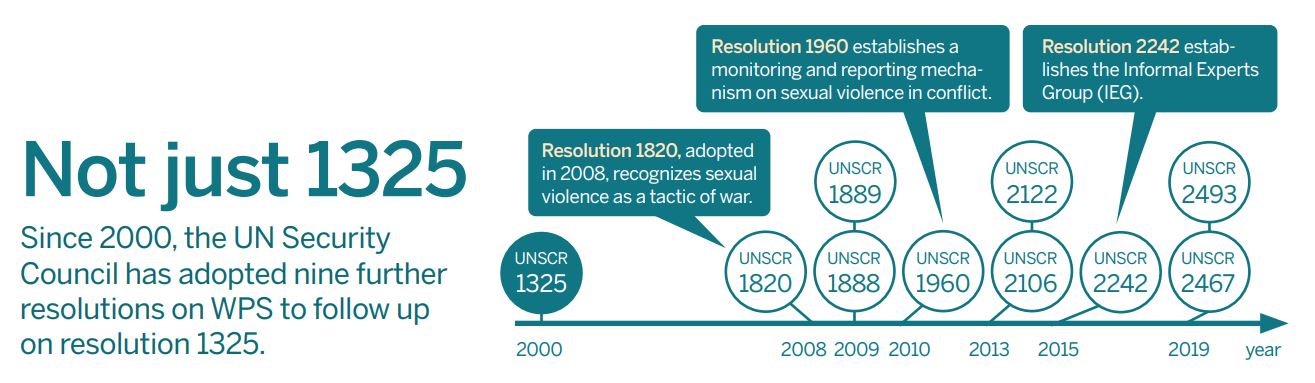

On 31 October 2000, the UN Security Council unanimously adopted its landmark Resolution 1325. Among other things, this aims at ensuring the role of women in prevention, conflict resolution and peacebuilding, and at protecting women from genderbased violence. Two African countries, Namibia and Rwanda, have played an important role in the adoption and follow-up of Resolution 1325. In Namibia, the UN Department for Peacekeeping Operations adopted the Windhoek Declaration on peacekeeping and a plan for gender mainstreaming back in May 2000. Besides, when the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 1325, it was under Namibian presidency. In the course of creating Resolution 1325, the experience of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda prompted a specific paragraph on gender-based violence; and on the resolution’s adoption, Rwanda’s UN Ambassador Joseph Mutaboba created a remarkable impression through his strong statement of support.

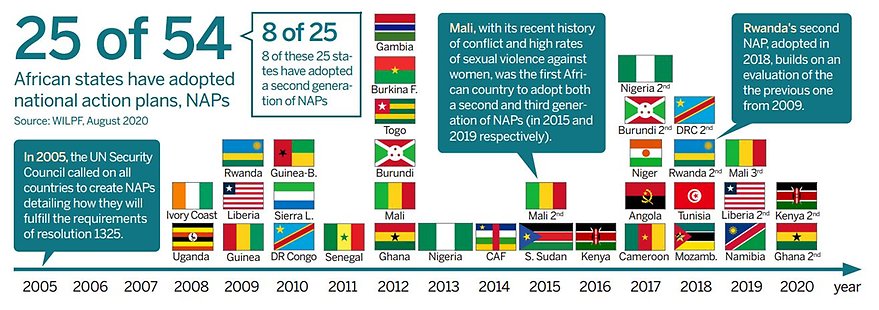

Twenty years on, there has been progress. An African Women, Peace and Security (WPS) architecture is in place, and a special envoy for WPS has been appointed. And yet, implementation of the resolution leaves something to be desired. This applies even to Rwanda, which is something of a ‘best case’ in terms of its commitment to the resolution: women have played a prominent role in the local gacaca courts post 1994; two national action plans have been drawn up; and there is large-scale representation of women at the national level (67.5 per cent of parliamentary seats).

This policy note focuses mainly on Rwanda, but also includes examples from other contexts, and some of its recommendations could therefore also apply in other African settings.

A strong state focus impairs women’s organisations

Resolution 1325, with its focus on states, includes only two provisions that mention the role of women’s organisations. The first (8b) is on measures to support local women’s peace initiatives and their role in implementation. The second (15) is on ensuring consultation with local and international women’s groups. This is something of a paradox, considering that the resolution came into being after intense lobbying by women’s organisations that provided training to Security Council members and that foregrounded experiences from conflict-affected countries. In the absence of well-functioning state structures, women’s organisations often play a role during and after conflict.

Participation is key – but only when meaningful

A UN presidential statement from 2004 calls on each member state to develop and implement a national action plan (NAP) to bridge the implementation gap. So far, less than half of the UN’s member states (84 out of 193) have drawn up such a plan. In Africa, 25 out of 54 have done so. Some African countries, like Rwanda, have developed more than one generation of NAPs. Some researchers, such as Helen Basini and Caitlin Ryan, who have evaluated the implementation of the UN Women, Peace and Security Agenda in Liberia and Sierra Leone, argue that NAPs are technocratic instruments monopolised by the international community; others claim that they are tools based on participatory processes designed for local solutions on peacebuilding and gender.

The first Rwandan NAP was launched in 2009, and the second in 2018. One of the pillars of the NAPs is participation. In Rwanda, the main successes lie in the increased participation of women at the national level and in the lower levels of the security sector (such as female police officers or troops). Furthermore, gender desks/focal points have been set up in the security sector including the Ministry of Defence. Research (for example by Bauer & Britton, Gouws and Madsen) on women’s political representation in Africa illustrates the fact that, for participation to be transformative, it needs to be substantive. Female members of parliament should build closer links to local women’s, men’s and HBTQI (homosexuals, bisexuals, transpersons, persons with queer expresssions and identities and intersex persons) organisations and commit to a gender agenda before, or in addition to, the party agenda.

Furthermore, gender desks need to have the proper tools, knowledge and influence at decision-making levels. At the lower levels of the security sector, female officers are often expected to perform specific duties in relation to female victims of violence – especially female troops in other African countries. However, participation based on gender per se seems to be a women-only thing. The higher levels of the security sector seem to be more difficult to penetrate. In the second NAP, the focus is on ‘meaningful’ participation, in line with the global discourse.

Rwanda’s self-image clashes with reality

In Rwanda, high levels of violence against women have persisted since the 1994 genocide (one third of all girls and women, between 15 and 49 suffer in their lifetime from physical and / or intimate partner violence (UN Women)). One explanation for the high levels is the country’s history of gendered violence; another is resistance to the official focus on gender, which some see as disempowering men. Violence against women is, according to this perspective, perceived as a defensive act for men and represents a traditional form of masculinity. Therefore, the NAPs have focused on protecting victims of violence and setting up ‘one-stop centres’ in every district, to provide a wide range of services and counselling. Even though prevention has often been neglected, it has been integrated into the new NAPs in a holistic way, combined with protection.

In the second NAP, Rwanda frames itself as the regional and global leading advocate on WPS, with an emphasis on foreign policy actors, gender mainstreaming and a humanitarian role in relation to refugees from, for example, Burundi or DR Congo. According to a monitoring report by Rwanda Women’s Network, gender issues have been marginalised in the big peace negotiations. Also, the new NAP states that Rwandan foreign policy is perceived as gender neutral, thus leaving intact the patriarchal nature of most military priorities and spending.

In Namibia, the WPS work lies closer to the centre of power

In African countries, the work on NAPs is often led by central gender-policy-coordinating units inside government. These national gender machineries spearhead the WPS efforts in 75 per cent of cases. They are often quite weak and underfunded, and have long ‘to do’ lists. In Rwanda, the national gender machinery – the Ministry of Gender and Family Promotion – also suffers from these shortcomings, as well as from a lack of continuity, with a high turnover in staff and ministers. The work on WPS is supported by a steering committee, which includes other ministries and representatives from academia and civil society. During the first NAP, the women’s umbrella organisation Pro-Femmes – Twese Hamwe was the secretariat for the steering committee; but under the second NAP, the Ministry of Gender and Family Promotion has done more to centralise the work (despite its own shortcomings).

Namibia has a different model. Here, the work on WPS is coordinated by the more powerful Ministry of Defence and Veterans Affairs, while the Ministry of Gender Equality, Poverty Eradication and Social Welfare is responsible for monitoring and evaluating.

The four pillars of the Women, Peace and Security agenda

- Participation.

Women's equal participation and influence with men and gender equality in peace and security decision-making processes at all levels. - Prevention.

Prevention of conflict and all forms of violence against women and girls in conflict and post-conflict situations. - Protection.

Protection of women’s rights in conflict-affected situations or other humanitarian crises, including protection from gender-based violence in general and sexual violence in particular. - Relief and recovery.

Access to health services and efforts to meet women’s needs in repatriation, resettlement, disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration programmes.

Local experiences support the global agenda

The women’s organisations play an important role in promoting the WPS agenda – especially due the challenges faced by the national gender machineries. They focus on inclusive peacebuilding, and not just ‘making war safer for women’ which means integrating women into military structures. They have recently taken the initiative to translate Resolution 1325 into local languages. They have also formed a network within the international project ‘Women Count: Security Council Resolution 1325’, where they have contributed with advocacy work and critical perspectives on the national efforts. In Rwanda, women’s organisations established the umbrella organisation Pro-Femmes – Twese Hamwe in Kigali in 1992. It has been rewarded by UNESCO and the Gruber Foundation for its work in building empathic cooperation across ethnic divides. Examples of other organisations formed in the wake of the genocide are AVEGA Agahozo (the Genocide Widows’ Organisation) and the Rwanda Women’s Network, with its ‘Village of Hope’ for victims of gender-based violence and its income-generating activities. In Rwanda, the focus on WPS has given the national women’s organisations more clout, for example through part of the NAP steering group.

However, at the local level, evidence from Rwanda (as well as Liberia and Sierra Leone) indicates that international actors, including the UN, have often marginalised the experiences women’s groups have of peacebuilding and gender. For example, the international community has failed to include different local understandings of gender as complementary. However, the focus should not only be on localisation of the NAPs, as is often stated, but on bringing local experiences of peacebuilding centre stage on the global WPS agenda.

Brooms to sweep away the detritus of the past

The WPS agenda is often regarded as synonymous with a generalised focus on ‘women’, understood as the apolitical and peaceful gender per se. Therefore, it is important with more inclusive and diverse WPS agendas and ensure the voices of different women are acknowledged – for example, in terms of differences in age, class, ethnicity, disability, geographical location and sexuality.

Paradoxically, this unifying and homogenising discourse has facilitated the adoption of Resolution 1325 in Rwanda, as women – in a generalised plural – are seen as ‘new brooms’ able to sweep away the detritus of the past. Besides, in post-genocide Rwanda, it is not permitted to refer to ethnicity, which hampers an intersectional focus. However, in the new NAP, some elements of differentiation can be identified, for example based on disability in relation to protection or prevention.

With a focus on ‘women’, the engagement with men and masculinities in the WPS agenda has been rather limited and unsystematic, probably limiting the effectiveness of the agenda within the masculinist security sector. In Rwanda, President Paul Kagame is an ambassador for the UN HeForShe initiative, which seeks to involve men in the achievement of equality, by taking action against negative gender stereotypes and behaviours. Also, a Rwandan Men’s Resource Centre has been formed to support alternative positive forms of masculinities. However, more localised efforts may be needed to reach marginalised masculinities, for example in terms of poverty, homosexuality, etc, and to transform masculinist institutions in the security sector.

Underfunding causes strategic reframing

The 2015 Global Study commissioned by the UN Security Council identified a worrying lack of funding, and UN Women has characterised underfunding as the most serious and persistent barrier to implementation of Resolution 1325. A recommendation was made in the Global Study that 15 per cent of all spending on peace and security should be earmarked for projects on women and gender equality.

Generally, most of the NAPs make either no or very little mention of budget, according to a study by Shepherd from 2020. In Rwanda, the 2009 NAP included a specific budget related to a donor roundtable, and was supposed to be linked to efforts at gender budgeting (which is itself a resource-demanding exercise). However, the plan remained underfunded. The 2018 NAP does not include any specification on funding, raising the question of whether the plan is fully funded. Both the Ministry of Gender and Family Promotion and Rwanda’s women’s organisations are dependent on external donors, especially UN Women, for their WPS work. Evaluation of the first NAP was delayed due to lack of external funding, which explains the long time (nine years) between the first and the second NAP.

Furthermore, the total funding for women’s organisations in Rwanda has been shrinking, as donors look to other apparently more urgent – conflict settings, for example DR Congo. Therefore, the national women’s organisations are strategically framing their activities in line with the WPS agenda to attract more resources.

Covid-19 calls for feminist leadership

Climate change, violent extremism and other ‘new’ threats to peace and security have been included in recent NAPs in many African countries. With its focus on participation, protection and the prevention of gender based violence – and not least a fourth pillar of economic relief and recovery – the WPS agenda seems to provide a suitable framework for addressing these gendered challenges. Recently, Covid-19 has been added to the list of challenges.

Covid-19 calls for feminist leadership in the political sphere and for the need to consider gender issues in high-level fora where decisions on Covid-19 are made and resources allocated. Covid-19 highlights the urgent need for feminist perspectives to deal with the gender consequences of the pandemic – e.g. increased domestic violence due to lockdowns, isolation at home, and fear of the virus preventing women from approaching help

facilities. It also stresses the need to focus on women in the informal sector, as well as the economic consequences of lockdown. In Rwanda, the economic recovery plan addresses neither the conditions of informal workers nor gender perspectives, despite the high level of women’s political participation. This is because national gender institutions were not involved in its drafting.

Recommendations

- Make the existing resolutions work, rather than add new ones. The UN and all the proponents of Resolution 1325 have already shown that they can ‘talk the talk’; now is the time for them to ‘walk the talk’. Even though the follow up resolutions have sharpened the language over time, it was not possible to secure language on sexual and reproductive health and rights of wartime victims due to conservative forces in the most recent ones. Thus there is a risk for a set-back.

- Ensure that the initiative and the agenda on how to move forward in the WPS work lie in Rwandan hands, so as to guarantee a locally designed solution. This also applies to other African countries that are dependent on funding from the international community. Key to achieving this is to secure core funding for the NAPs through the national budgets. This will break the dependency on foreign donor agendas – even if it means risking some initiatives, due to the withdrawal of funding.

- Strengthen those national gender machineries that spearhead the WPS work, by providing more resources, and greater stability and capacity building. Follow the Namibian example of identifying new ways of cooperating with other, more powerful government units, such as the ministries of defence or finance on Resolution 1325.

- The NAPs have to acknowledge the important role of the national women’s organisations, in terms of both involvement and resources. The grass-roots experiences of local women’s groups (which form the majority of women organising) have to become more integrated and linked to the national and global levels. Build mechanisms to promote local initiatives, based on indigenous processes, in Rwanda and other African countries.

- The NAPs have to diversify the way in which they frame ‘women’ and address the different needs and contexts of different groups of women, based on, for example, age, class, ethnicity, disability, geographical location and sexuality. They have to include women’s organisations/groups representing different women, including those on the margins of current WPS work – for example, those that have not been included in the steering committee.

- Men have to be engaged in the WPS agenda. Supporting national men’s organisations and their local programmes could help reach out to marginalised masculinities and address gendered institutional barriers in the upper levels of the masculinist security sector.

- Strengthen the gender mainstreaming of the budgets for peace and security, including setting specific targets and indicators in line with the recommendations from the 2015 Global Study.

- Use the thinking and pillars of the WPS agenda to address the gendered challenges of new health threats like Covid-19, which could be framed as ‘security threats’. However, the Covid-19 action agenda should not be watered down with a long laundry list of other gender issues that need to be resolved within the WPS framework.

This policy note is inspired by the conclusions from the symposium Gender and Peace in Africa: Taking Stock of 20 Years with Resolution 1325 (Stockholm 9–10 March 2020), which was co-organised by NAI and the Namibian Embassy in Sweden and was supported by Riksbankens Jubileumsfond.

Research on the topic

The NAI policy notes series is based on academic research. For further reading on this topic, we recommend the following peer-reviewed articles:

Diana Højlund Madsen (2018): ‘“Localising the Global” – Resolution 1325 as a Tool for Promoting Women’s Rights and Gender Equality in Rwanda External link, opens in new window.’, Women’s Studies International Forum, 66, 70–78.

External link, opens in new window.’, Women’s Studies International Forum, 66, 70–78.

Diana Højlund Madsen (2019): ‘Friction or Flows? The Translation of Resolution 1325 into Practice in Rwanda’ External link, opens in new window., Conflict, Security and Development, 19(2), 173–193.

External link, opens in new window., Conflict, Security and Development, 19(2), 173–193.

Diana Højlund Madsen & Heidi Hudson (2020): ‘Temporality and the Discursive Dynamics of National Action Plans on Women, Peace and Security from 2009 and 2018’, International Feminist Journal of Politics, External link, opens in new window. 22(4), 550-571

External link, opens in new window. 22(4), 550-571