Community response makes for effective prevention

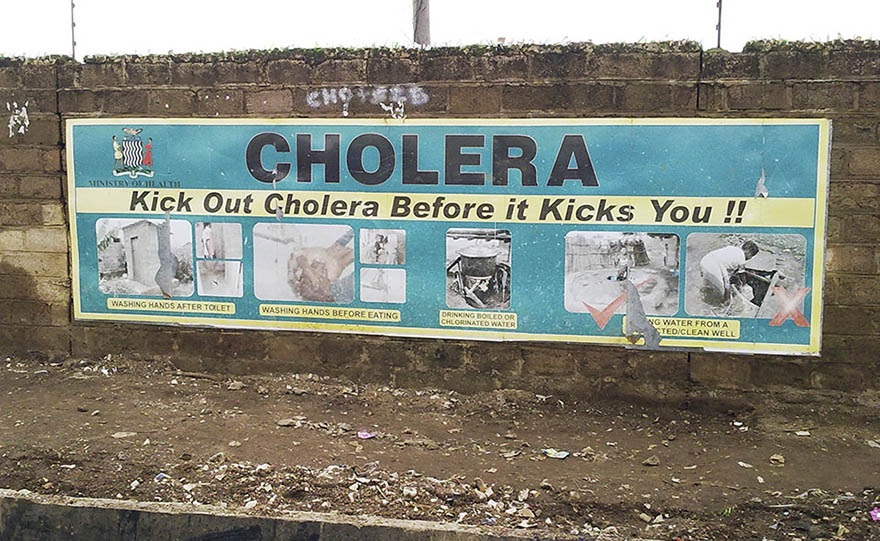

Cholera prevention sign board in Zambia. Photo: SuSanA

As southern African countries brace for the coronavirus pandemic, prevention in communities is built on experiences gained during outbreaks of cholera, hiv/aids and malaria, according to NAI researcher Patience Mususa.

Most southern African countries have put in as much effort as possible in addressing the Covid-19 pandemic, according to Mususa, an anthropologist who studies the dynamics of urbanisation in Zambia and elsewhere in southern Africa.

The focus is on prevention. In particular, arresting local transmission of Covid-19 to urban informal settlements.

To this end, control systems have been setup at airports where travellers’ contact details are collected. People are advised to self-quarantine and those who show symptoms of the virus are tested.

Zambian health authorities have sent text messages to all citizens on their phones about the symptoms of Covid-19 and what people need to look out for, with an appeal to call a contact number and report people who appear to have symptoms.

“It is a form of community surveillance”, according to Mususa, who says other countries are taking similar steps.

NAI researcher Patience Mususa. Photo: Mattias Sköld

Beyond local surveillance, authorities across southern Africa are also drawing on strategies of popular sensitisation, that have previously been used in health crises, such as for hiv/aids and cholera. Radio and television talk show hosts and musicians have been enlisted to popularise health messages.

“People are informed about sneezing and coughing into the elbow of the arm, to wash their hands with soap, and when they don’t have access to water, to use hand sanitiser.”

Mususa says that the authorities purposely use traditional channels, rather than primarily social media, since many people in informal settlements lack internet access.

“When it comes to informal settlements, these messages move quite well”, she says.

In public markets, local authority representatives, police officers, volunteers, and sometimes the army perform clean-up duties and spray disinfectant, in the same way as in recent cholera outbreaks.

“By doing this, authorities are also saying to people that there is a potential public health crisis at hand.”

The private sector is also mobilised. Shops and other businesses are donating water buckets with improvised taps, and containers with water so those running small businesses can have a place where people can wash their hands. They also go around donating hand sanitiser.

Well aware of their weak health systems, countries in the southern African region, depend heavily on preventive measures to deal with the emerging health crisis, according to Mususa.

There has been a strong response from all segments of society, which according to Mususa highlights key characteristics of public health that can be traced back to epidemics such as the plague of London in the 17th century: a unified response is needed because even when pandemics affect those with less resources the worst, the wealthy have learnt that they are not immune from contagion.

For the wealthy, the risk of falling ill from the coronavirus is different from other health worries. While affluent Zambians can travel to India or South Africa, to treat heart conditions or have eye surgery, with Covid-19 going abroad is not an option.

While public distrust of the state generally is widespread in southern Africa, when it comes to health crises people show greater trust in authorities, according to Mususa.

“In general, within the public health realm, when police tell people to move – to give way to cleaning, on the whole, most comply. People’s main concern is how fast they can go back to making a living. Previous epidemics such as cholera have taught them that an active response to prevent the virus from spreading effectively means a quicker return to business. I would say that it is here that there is a synergy between communities working closely with the state.”

Mususa says that since the hiv/aids crisis in the late 1980s, which coincided with massive spending cuts in health and other social services, many people have turned to community responses.

“Health in economically stressed contexts is increasingly addressed at the community level. People improvise, create their own semi-protective clothing and find ways and means to care for sick family members and others. They follow up on public health messages such as not to gather in large groups at funerals, and try within their means to contain the spread of an epidemic.”

Mususa thinks that the world can learn something from the community responses of southern Africa, especially for places where the state may be weak or slow to act.

“Epidemics show the deep interconnections across a variety of spaces. Maybe a bit of popular sensitisation might help people and communities in the West who are anxious and don’t know what to do, especially when the messaging might not be so coherent across different audience groups. It is crucial that health systems are well funded to provide critical material provisions such as ventilators. Dealing with pandemics however, also needs to encompass societal response.”

She fears though that since the whole world is falling under the weight of dealing with the crisis, it might be difficult to find the kind of solidarity that emerges from addressing problems collectively and learning from one another.

TEXT: Mattias Sköld