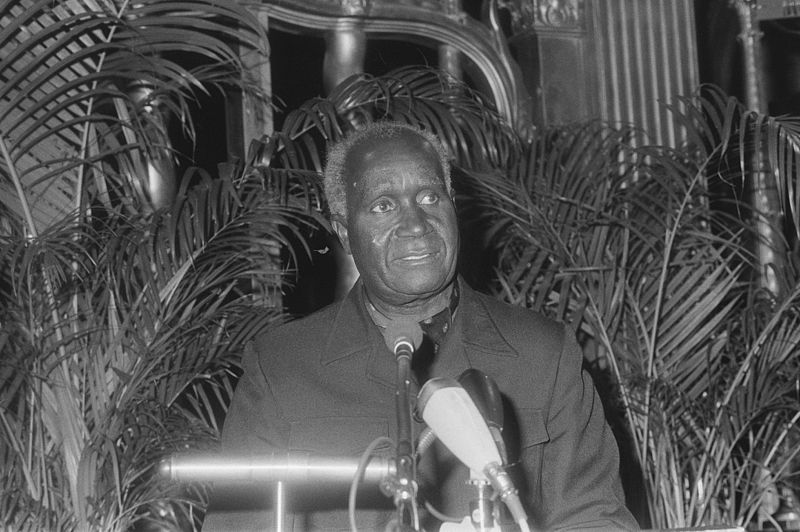

Kenneth Kaunda

President of Zambia. President of the United National Independence Party

Tor Sellström: I would like to clarify that the objective of the interview is to discuss the involvement of all the Nordic countries in the liberation struggle in Southern Africa.

Kenneth Kaunda: Well, it was Olof Palme who led the Nordic countries in this process. It was his contribution which aroused the interest and the feelings of the other Nordic countries. They also made very wonderful contributions, there is no doubt about that. But I am merely being factual when I say that it all started with Sweden.

Kaunda in 1986. Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

Tor Sellström: You went to England as a young man in 1957 and met the Labour Party and others there. Did you at that time have any contacts with a Nordic country or organization?

Kenneth Kaunda: No, not at that time. We were very insular in those days. We were more or less locked out. We had no contacts with the outside world. For example, in 1954 a few colleagues and myself wanted to organize a Pan-African Congress for this region. We invited some people from the neighbouring countries, but even they were banned. Only one man from the United Nations, a Burmese, managed to attend. We were very insular. It was not our choice. It was the way the colonial masters wanted it to be. When I visited England it was the first time that I went outside the region.

Tor Sellström: Were your first contacts with the Nordic countries made then after Zambia’s independence in 1964?

Kenneth Kaunda: No, it was a little earlier. In fact, I visited Sweden in 1962 as a guest of the late Olof Palme’s party. I was very well received, indeed. I felt very much at home.

Tor Sellström: Perhaps you visited with Oliver Tambo, who also went to Sweden in 1962?

Kenneth Kaunda: No, he must have gone on his own. That was the first time that I went to Sweden, but my first contacts with the Swedish people were, I think, at a World Assembly of Youth (WAY) conference in Dar es Salaam. I met Swedes there and I kept my contacts with them until 1962.

Tor Sellström: The Nordic involvement with Zambia started in response to an appeal by the United Nations to assist Lesotho, Botswana, Swaziland and Zambia?

Kenneth Kaunda: Yes. That is how we organized scholarships for some of our students. For example, Alex Chikwanda, who was in my government for a long time, studied in Sweden. Rupiah Banda came under the same scheme. I organized those scholarships.

Tor Sellström: I know that Rupiah Banda studied at the University of Lund together with Billy Modise, who is now South Africa’s ambassador to Canada. They had a little band, called ‘Billy and Banda’.

Kenneth Kaunda: I did not know that!

Tor Sellström: They were also among the founders of the Swedish solidarity movement. In 1969, the Swedish parliament decided that it was legitimate to give direct support to the liberation movements. The other Nordic governments followed later. How did you view the Nordic position?

Kenneth Kaunda: Well, first and foremost, let me say that I am sure that I express the view held by many leaders of this region. Firstly, because of the time when the assistance was given; secondly, the way in which it was given; thirdly, the type of aid that it was; and, fourthly, the impact it had on us, made us all realize that the Nordic countries had something special to contribute. Not only to Southern Africa, but to the struggling masses and to God’s people the world over. They were very human. They did not grant aid to us because they expected something in return. They granted aid to us because they knew that fellow human beings needed that aid, almost saying to themselves that ‘if we were in that position and they were in ours, we know that they would do the same thing to us’. So, really—and in many ways—at the time of our struggle for independence in Zambia and in the neighbouring countries the impact of that aid was such that even if we had had—I am not saying that we did—but even if we had had some anti-white feelings, that aid would have changed our minds.

Tor Sellström: Did you not feel that there were strings attached to the aid? Any hidden agendas?

Kenneth Kaunda: This is exactly what I am saying. The aid had no strings attached. This is what I am talking about. It was: ‘Our fellow human being needs assistance. We will give it to him as best we know how.’ Really, it helped a lot to make us what we are. That contribution was very important.

Tor Sellström: Did you feel that the Nordic countries had different outlooks depending on their international alliances? Sweden was neutral, Finland had a ‘special relationship’ to the Soviet Union and Denmark and Norway were members of NATO?

Kenneth Kaunda: Well, when we became independent we started off as truly non-aligned and we saw something similar in Sweden on these issues. Non-alignment did not mean that we were saying to anyone that we are holier than thou. When they made a mistake, we said to the West that according to us they had made a mistake. And if they did something right, we praised them equally strongly. The same goes for the East. If they did something good, we praised them. But if they did something wrong, we condemned them.

To make this properly understood, let me give you an example on Zambia’s behalf of what we did in two clear cases: when the Americans were bombing the Vietnamese people, using napalm bombs and things of that nature, I spoke about it on behalf of Zambia several times in public, condemning the action. I remember that I twice spoke about it in parliament, dealing with foreign policy matters. I was condemning it. But when the Americans stopped bombing the Vietnamese and it ended, we became friends again. There was nothing more for me to condemn. Then, some day in 1968 the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia. I remember that I was at the border with Tanzania when this happened. I was listening to a broadcast from BBC and I heard that the Soviet Union had invaded. That same morning I addressed a huge mass rally. I condemned the Soviet Union and I made it clear to the rest of the world, and to them as well, that if they were going to withdraw their aid to us because of my condemnation, they were free to do so.

Now, coming back to Sweden, I remember that it was under Olof Palme that the young men and women in America who did not want to go to Vietnam found a place there.

Tor Sellström: In the case of Sweden, Olof Palme marched with the North Vietnamese ambassador and condemned the American bombings to the extent that the United States withdrew its ambassador. On the question of Czechoslovakia, Palme condemned the invasion and talked about the new Czech government as ‘the cattle of the dictatorship’. Your positions were very similar?

Kenneth Kaunda: Very similar, indeed. I gave these examples, because I know where Olof Palme stood on these issues. He received these students when they refused to go to Vietnam and they were persecuted by the American government. They ran away and found solace in Sweden. We had a very similar stance on these issues.

Tor Sellström: You also supported liberation movements that received material and military assistance from the Communist bloc. Here some would argue objectively that you, Palme and other Nordic leaders were supporting the East in an East-West confrontation?

Kenneth Kaunda: Those who did not know the leaders of the liberation movements might have thought that way. But for those of us who knew them it was different. They were pushed against the wall and they had to get arms from the Soviet Union or the People’s Republic of China simply because they had to fight. You can refer to the Lusaka Manifesto on Southern Africa, where we—the Heads of States of this region—made it clear that the liberation movements that could attain independence through non-violent methods should do so. But we had no moral or political right in the situation prevailing at the time to say that if they could not attain independence through peaceful means: ‘Do not fight!’. We had no right at all. We urged them: ‘If you can negotiate peacefully, please, by all means, do so. But if you cannot, we will support the means you decide to use.’ And this is what happened.

It did not mean that we were siding with the Soviet Union or the People’s Republic of China. If the West had given them arms, the liberation movements would have been very happy to receive them. They did not have a choice in this matter. They had to go to the countries where they could receive this aid, like the Eastern European countries and the People’s Republic of China, who supported them and backed them very strongly and fully.

We knew that the situation was not easy. When it comes to the Portuguese colonies, I myself met with political leaders on several occasions. I met settlers from Angola and Mozambique. I wrote to them and my argument was: ‘Look, your countries have been under Portuguese rule for centuries. There is no way that you will lose if you hand over power peacefully, because culturally they will be tied to you. They are just part and parcel of you now, so you are losing nothing. You have everything to gain by handing over power to the majority of the people.’ But they continued to behave as if Angola, Mozambique and the other colonies were truly provinces of Portugal. That is how the liberation movements embarked upon the armed struggle.

Similarly, when we were dissolving the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, we did not dissolve it because we were against larger units, but because it was a second South Africa being imposed on us. We objected to it and we fought against it. When we were ending the Federation, I said to the last Governor: ‘Please, let me meet the leaders of the white minority groups, the Prime Minister and the Deputy Prime Minister’. Guess who was the Deputy Prime Minister? Ian Douglas Smith! I said to them: ‘Gentlemen, when we become independent, we will recognize you as white nationalists in Rhodesia. But we are conscious of the fact that the indigenous nationalists, the black nationalists, are by far the majority and that you will have trouble with them. So, please, if you ever need our services to try and be bridge-builders, we will be quite happy to assist.’ The Prime Minister then said: ‘Mr. Kaunda, if we did not know that you are serious and sincere, we would have told you to mind your own business.’ Well, I was minding my own business until Ian Smith landed at State House here in Lusaka with his army and his choppers, coming to ask for assistance.

That was at a time when it was taboo for African nationalist leaders to meet those people. But because my conscience was clear, I met them. That is how I met the late Vorster, Botha and finally de Klerk. It was to show that if they would negotiate we had nothing against them at all. We were not anti-white as such. This is the point I made earlier, and which the Nordic people strengthened so much in us.

Tor Sellström: At the time of independence, you—and also President Nkrumah of Ghana—tried to establish diplomatic relations with South Africa as a means not to be subdued or to open up space?

Kenneth Kaunda: Yes, I said to them: ‘If you can look after my ambassador in the same way that you look after white ambassadors, we can establish relations.’ But they could not.

Tor Sellström: When it comes to the different liberation movements, the Nordic countries supported MPLA in Angola, FRELIMO in Mozambique, ANC in South Africa, SWAPO in Namibia and both ZANU and ZAPU in Zimbabwe. Also here your position was very similar?

Kenneth Kaunda: Yes, exactly the same. That is clear. That is also how we worked. In the case of South Africa, in the beginning we recognized both ANC and PAC and allowed them here. But what happened was that PAC had a camp for their cadres in Livingstone and that they decided to kill some of their members, suspecting that they were sell-outs or South African agents, reporting them to the South African authorities. I came to hear about it and said to PAC: ‘Please, do not do that. On this soil of Zambia, I am the only one who is constitutionally allowed to take life. I do not like it, but the law says that I should do that when the High Court has found somebody guilty and has so decided. So, do not do that.’ However, they were going to kill them, so I gave instructions to the Zambian army to get into their camp and save the lives of those people. Fortunately, we did it without loss of life. I then said that they could not work from here, because they were defying my orders and there was no way that we could have two governments in the country.

They were sent to Tanzania. But when I became chairman of the Frontline States and also chairman of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), I had to welcome them back. Because in that capacity I had to receive all the movements that were recognized by the OAU. That is how PAC came back to Zambia after many years.

Tor Sellström: The Nordic countries supported the liberation movements in Zambia through humanitarian assistance. I presume that it was with your knowledge and approval?

Kenneth Kaunda: Yes, we accepted it, indeed. We were very happy to do so. We knew what kind of aid they were giving and how it was given. It was given without strings. It was aid given because certain fellow human beings were in great need.

Tor Sellström: Was it strictly civilian?

Kenneth Kaunda: Yes, strictly civilian. I might add that if the Nordic countries for any reason had given them armed support, we would not have had any objections at all. Not with the Nordic countries.

Tor Sellström: In 1972, the ZANU leader Herbert Chitepo came to SIDA in Stockholm and said: ‘We are about to launch the armed struggle and the result will inevitably be retaliation by the settler regime and refugees pouring into Zambia. So, can you please assist us in Zambia?’ It was quite amazing. Here you had a representative from a liberation movement coming to a Western country and exposing their military plans. I guess that it says a lot about the trust between the parties involved?

Kenneth Kaunda: Exactly. That is very true. That was supposed to be top secret information, but in Sweden he talked freely because of that trust.

Tor Sellström: It eventually led SIDA to purchase a farm for ZANU here in Zambia. Later SIDA financed the purchase of farms for ANC and SWAPO. Did you, in this context, feel that there was undue interference by the Nordic countries in the affairs of Zambia?

Kenneth Kaunda: Certainly not. Without hesitation, none at all. At least none that I know of or that my colleagues who were dealing with these matters knew of. Nothing at all.

Tor Sellström: Because at some stage, Zambia and the Nordic countries could come on different courses? I am, particularly, thinking of the Angolan issue in 1974-75.

Kenneth Kaunda: Exactly. The background was that we had kept UNITA away from Zambia, but after the coup in Portugal I sent my Minister of Foreign Affairs—guess who? Vernon Mwaanga!—to speak to his African colleagues. They met in Cameroon. I said that now that there is a change in Portugal, let Africa open up to all the Angolan liberation movements. Let them be accepted by OAU. If we do not do that, there will be all sorts of internal problems in the future. That was in 1974. Indeed, Mwaanga spoke to his colleagues and the Foreign Ministers accepted that position and passed a resolution which in turn was accepted by several Heads of State. After that, in 1974-75, things began to happen very fast. The Heads of State of this region met in Kananga and we agreed that if Agostinho Neto were to become President we would support him. We would also support Savimbi becoming Minister of Defence and we would support de Andrade.

Zambia was later detailed to try and bring the Angolans together. We met all the factions here, at a farm. Reuben Kamanga was my representative. He had been in Cairo and to most other centres when we were struggling for our independence and he knew most of the Angolan leaders. They met for fifteen days. And failed! The following day, I asked to see my brother, the late Neto. I loved that man. He was a Marxist-Leninist and I am a Christian, but we were very good friends. We met for sixteen hours at State House. No breaks for lunch, only tea and scones. I tried to persuade my brother and said: ‘Look, you are an organizer. Please, bring all the parties together. It must be possible to do that, because for the time being you need a coalition government.’ But I believe that he was under pressure from the Soviet Union. We could not accept that at all. I stuck to my approach. That is when I made a statement saying that it was like letting a tiger’s cubs into Angola. It would bring no peace at all. I referred to the Soviet Union and Cuba. Again, Fidel Castro is a very good personal friend of mine, but I attacked the Soviet Union and I attacked him too. Because of the fear I had that it would bring problems to Angola.

And, indeed, what followed was very sad. We were forced to have an OAU Heads of State summit meeting. Julius Nyerere and myself had vowed never to go to a summit under the chairmanship of Idi Amin, who was then the chairman. We refused to recognize him. But this time we were forced to go to the summit. And, unfortunately, of the 46 countries that voted, 23 were for and 23 were against. It was very sad. It was a lost case. As I said to President dos Santos when he came here for a state visit: ‘One does not settle scores. It is not right. I told you so.’ But that is what I discussed with my brother Neto.

Tor Sellström: Did you have any consultations—informal or otherwise—with Olof Palme? He was very much involved in some sort of diplomatic exchange between Neto, Castro and Kissinger in the beginning of 1976.

Kenneth Kaunda: No. I did not know about that, but it shows the point I was making earlier. Even a man like Kissinger recognized that only somebody like Palme could talk to Neto about their differences. He had to fall back on someone who had defied him during the Vietnamese war. That’s interesting.

Tor Sellström: After the assassination of Herbert Chitepo in 1975, you detained a number of ZANU people while Sweden gave humanitarian assistance to ZANU. Did that create any friction between you and Sweden?

Kenneth Kaunda: No, certainly not. We suspected that the assassination was an inside job. At the funeral of the late Chitepo I said that my government would do everything possible to find out who had done this, arrest them and bring them to a court of law. We set up a Special International Commission. What I did not know then—I only came to know about it much, much later; in fact, after I had left government—was that one of my own ministers actually had been persecuting ZANU, because he was a supporter of ZAPU. I did not know that at all. A researcher in Zimbabwe found out about it. Well, my minister was not supporting ZAPU as such. He was an agent of Ian Smith’s, informing on ZANU. He was given instructions to disorganize ZANU within Zambia. My colleagues on the ZANU side unfortunately believed that he was acting like that on my instructions. So they were hostile for a long time. I did not understand why, because I thought that I was giving equal support to all the liberation movements. That is until I left government and the researcher was told by one of Ian Smith’s former agents that this is what had happened: ‘Kaunda did not know about it.’ This researcher—David Martin—was a strong ZANU supporter. He had earlier published a book against me, but now he apologized.

Tor Sellström: There was also the so-called Shipanga affair in SWAPO in Zambia in 1976. It involved three parties that were very close to the Nordic countries, namely SWAPO, Zambia and Tanzania. Was there any pressure by the Nordic countries, demanding that the detained SWAPO leaders should be duly processed or that they should not have been detained at all?

Kenneth Kaunda: No, not that I know of. It was a very difficult thing for us. Very difficult, indeed. We really tried as humanely as possible to maintain law and order and to do things as established by law. On the other hand, our commitment to the cause of independence and freedom of the peoples of Southern Africa was such that there were certain things that we had to do. For example, accepting to launch the armed struggle from here was not easy at all.

By the same token, it was not easy for me to defy a matter that was before the High Court and give instructions to fly somebody who was going to appear in the High Court of Zambia out of the country in our own plane. It was not easy at all. But when we weighed the two, it was quite clear where our duty lay. So I had to order that Shipanga and the others be taken to Tanzania. But as far as I remember we had no pressure at all from the Nordic countries.

Tor Sellström: I guess that it was a difficult issue for all the parties involved?

Kenneth Kaunda: Yes, for all of us. For the Nordic countries and for ourselves, both in Zambia and in Tanzania.

Tor Sellström: Later, when Shipanga was released, he went to Sweden, where he formed SWAPO-Democrats. That was perhaps symbolic?

Kenneth Kaunda: Yes, and in a way helpful to us!

Tor Sellström: Did you normally consult with the Nordic countries at the United Nations and in other international fora?

Kenneth Kaunda: Yes, indeed, on Southern Africa. Certainly, there were standing instructions that my ambassadors should consult with the Nordic governments and—if we needed support— that they should seek that from them.

One problem was perhaps that the Nordic countries as a matter of principle could not vote for resolutions containing calls for armed struggle?

Kenneth Kaunda: Yes, certainly, but we understood that very well. There was no problem with that. Not at all.

Tor Sellström: With regard to economic and development issues, the Nordic countries at an early stage formulated the so-called Oslo Plan to coordinate their policies and from 1984 they met with the Foreign Ministers of the Frontline States on a regular basis. The Finnish Prime Minister Kalevi Sorsa also took an initiative to broaden the Nordic assistance to SADCC and from 1986-87 all the Nordic countries applied economic sanctions against South Africa. There developed what one could call a region-to-region cooperation?

Kenneth Kaunda: That is true. We appreciated that. It strengthened us a lot. We quarrelled publicly with the big powers of the West on the issue of sanctions against South Africa. Here we were, small countries that were suffering, paying a high price, only supported by countries like the Nordic countries and the People’s Republic of China. The big powers continued to pay lip service to the struggle against apartheid. It used to pain us a lot and that is how some of us were said to be anti-West. But we were not. We were just anti-wrong. I gave the examples of the Americans bombing the Vietnamese and the USSR invading Czechoslovakia. These were matters of principle for us. Whenever we thought that something was wrong, we condemned it publicly. This did not place us on good terms with the Western countries, especially not with my ‘dancing partner’ Margaret Thatcher!

I remember when we were at a Commonwealth meeting in the Bahamas, where I was detailed to move a motion of sanctions against South Africa. Margaret Thatcher opposed it. We adjourned and met again after tea. I said: ‘Margaret, you are worshipping Mammon, not God.’ You could have heard a pin drop! There was silence amongst the Heads of State and Government. But, it was nothing personal. I was just arguing the point of sanctions. At another meeting in Canada, I said: ‘Margaret, you do not know Africa at all. It is important that you listen to the people who know these things’. I was not trying to make her look stupid or something like that. Not at all. I was just thinking of the sacrifices we made.

Tor Sellström: I remember reading that when you hosted the 1979 Commonwealth Conference in Lusaka—where you were to discuss the Rhodesia question—she demanded that the leaders of ZANU and ZAPU should not welcome the Queen at the airport?

Kenneth Kaunda: Yes. First she did not want Queen Elizabeth to come here at all. She said that it was too dangerous. All she tried to do was to sabotage the summit. She even went to Australia to try to win Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser over to her side. She could not. But because she trusted him, we made him the chairman of an internal meeting that we held here in Lusaka with her and her Foreign Minister, Lord Carrington. She tried to sabotage, but everything went well in the end.

Tor Sellström: Finally, it has been argued that support to one sole and ‘authentic’ liberation movement in the countries under colonial or apartheid rule was detrimental to the development of a democratic society after independence. How do you look upon that?

Kenneth Kaunda: I think that during the struggle it was important for us to support one strong movement, although in Zimbabwe the Nordic countries and ourselves in the Frontline States supported both ZANU and ZAPU. In South Africa as well. Now, I think that the situation changes after independence. I would have thought that, in terms of support, governments should support the peoples, but political parties should support the parties which think like they do. In that way you strengthen various voices towards the build-up of a democracy and we need a strong opposition.